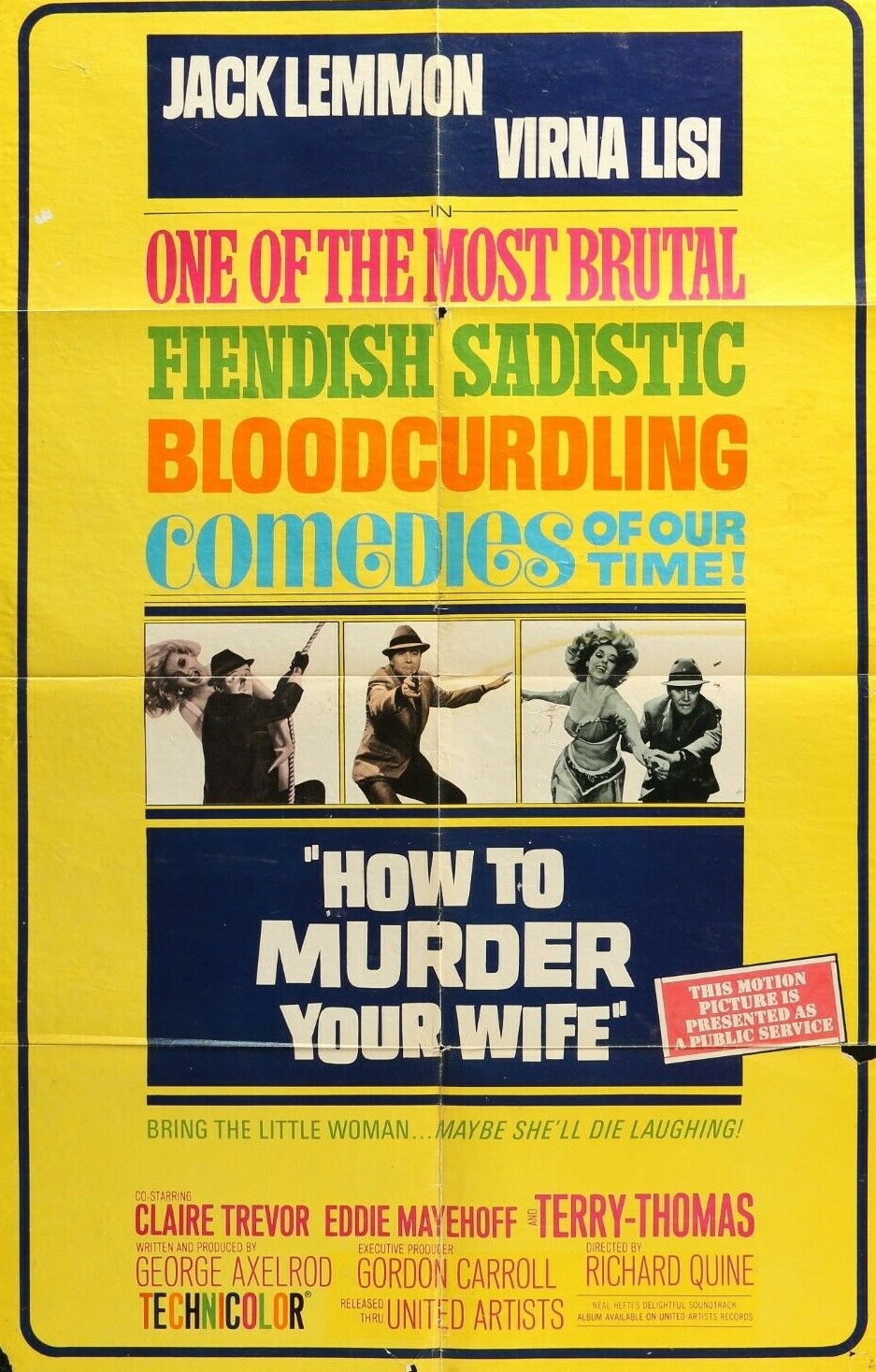

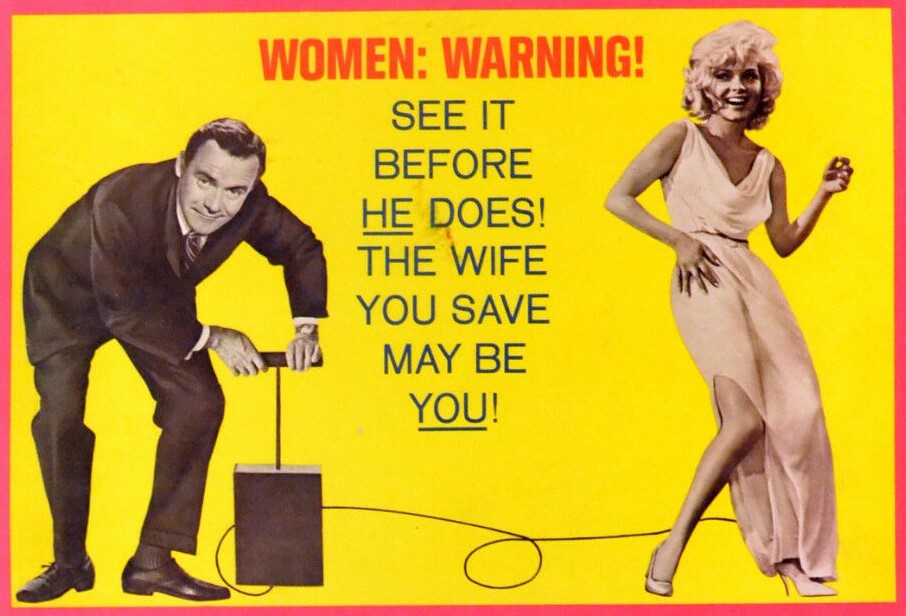

Men had a hell of a time in the 1960s to judge from this riff on marital strife that starts off like Walter Mitty meets The Odd Couple. It’s one of those daft comedies that only work on their own terms – and for the most part this works very well.

Dedicated bachelor Stanley Ford (Jack Lemmon), enjoying a host of one-night stands, ensconced in almost a bromance with butler and kindred spirit, the very English Charles (Terry-Thomas), makes the mistake of getting hammered at a drunken party and ends up married to a beauty queen (Virna Lisi). Although she is gorgeous and very loving – most scenes end on a fade as she devours him in kisses – and a good cook (though a bit lax by the high housekeeping standards of Charles), Stanley resents being burdened with a wife, especially when it costs him the services of his butler.

The biggest casualty is his self-image. He has fashioned his persona after his Bash Brannigan comic strip, syndicated to hundreds of newspapers, that permitted him the fantasy of being secret agent/adventurer/detective, fighting off bad guys and rescuing damsels in distress. Marriage inflicts a devastating change in his mental state, and he transforms from hero into hen-pecked booby.

In a bid to restore his self-esteem, and provide a fictional glimpse of freedom, he plans to murder his wife, if only in the comic strip. It has been Stanley’s working practice to act out and have photographed all the elements of his stories so Charles records the whole episode, from getting advice on how to drug Mrs Ford to (using a dummy) incarcerating her in cement. Unfortunately, Mrs Ford, outraged on discovering the illustrations for this particular comic strip episode, vanishes, leaving no explanation for her disappearance, except that various people witnessed him carrying out the supposed murder. He is arrested and put on trial.

You couldn’t make this up, but strangely enough, it is all very believable. The opening section where Stanley enacts the part of his action man Bash Brannigan in “The Case of the Faberge Navel” is just a delight. When the future Mrs Ford comes to explain exactly why she came to be jumping out of a birthday cake in a bikini, it is as daft as everything else.

However, the picture’s overall theme, the war between men and women, where men feel controlled, is somewhat dated. You might expect such a war to go nuclear when Mrs Ford dares to infringe on the sanctuary of a men-only enclave. The trial scene is particularly laborious in trying to determine that men are victims of controlling women. Despite that, there are some very funny lines that hit the nail on the head – men “are always guilty about something” declares Mrs Ford’s confidante Edna (Claire Trevor) whose strategy is always to keep men off-balance.

Jack Lemmon (The Apartment, 1960) has ploughed this path before, conspirator to the illicit, although generally to be found in the loser camp rather than, as, effectively here, despite his complaints to the contrary, in the winner’s circle with an enviable lifestyle and willing girlfriends to hand. There’s a gleefulness in his performance, the little boy getting away with everything, that turns into a small boy’s sullenness when it is all apparently taken away.

Italian star Virna Lisi (Assault on a Queen, 1966), in her Hollywood debut, is a delight. Her frothy sexuality goes down a treat but she is far from a dumb blonde, learning English from television, excellent cook, and wise enough not to go down Edna’s route of dealing with men. Terry-Thomas (Bang! Bang! You’re Dead!, 1966) delivers just as interesting a confection, a touch of ruthlessness to the stiff upper lip, high chieftain of the Male Protection League, reveling in the prospect of ridding the world of insidious influences like Mrs Ford. And there’s a welcome role for Claire Trevor (Stagecoach, 1966), especially when, in a party scene, she really lets go.

The other males, ranging from dumb and dumber to dumbest, totally lacking in Jack Lemmon’s charm, perfectly illustrate the need for a woman’s firm hand, among them Eddie Mayehoff (Luv, 1967), Sidney Blackmer (A Covenant with Death, 1967) and Harold Wendell (My Blood Runs Cold, 1965).

Richard Quine (The World of Suzie Wong, 1960) directed from an original screenplay by George Axelrod (The Secret Life of an American Wife, 1968).