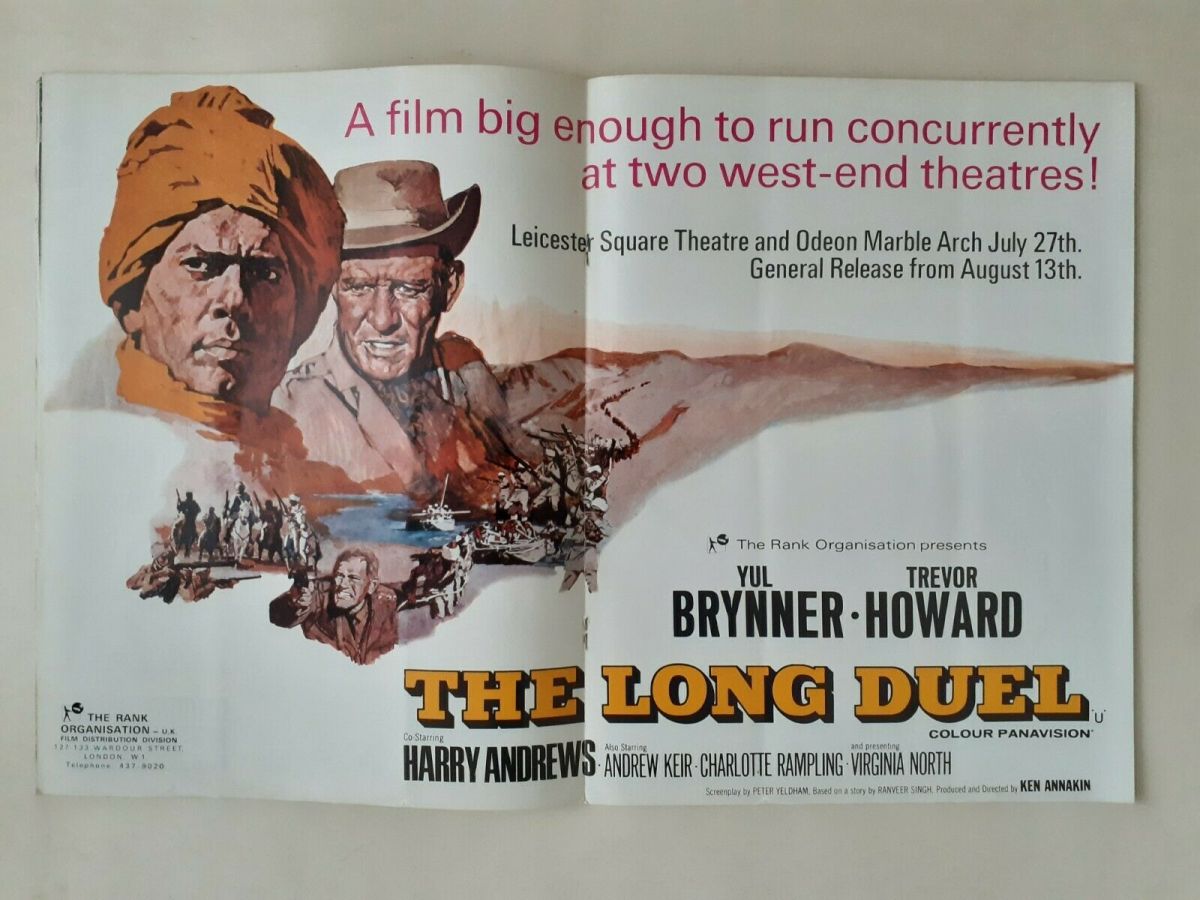

Surprisingly thoughtful action-packed “eastern western” with obvious parallels to the plight of the Native American. Here, the British attempt to shift nomadic tribesmen from their traditional hunting grounds in north-west India to “resettlements.” Set in post World War One India, the duel in question between tribal chief Sultan (Yul Brynner) and police chief Young (Trevor Howard) brims over with mutual respect.

Unusually intelligent approach for what could otherwise have been a more straight forward action picture, more critical of the British, whose idea of civilization is to turn everything into “a bad replica of Surrey,” than you would have expected for the period. Ruthless pursuit in large part because the British “can’t afford local heroes.”

After his tribe is taken captive with a view to forced repatriation by boorish police superintendent Stafford (Harry Andrews), Sultan organises a breakout, taking with him heavily pregnant wife Tara (Imogen Hassall) who dies while on the run. The Governor (Maurice Denham) of the province brings in Young – who knows the territory and is more familiar, through a previous career as an anthropologist, with the nomadic lifestyle, and largely sympathetic to their cause – to head up an elite force and bring to justice Sultan, whose men are now murderers.

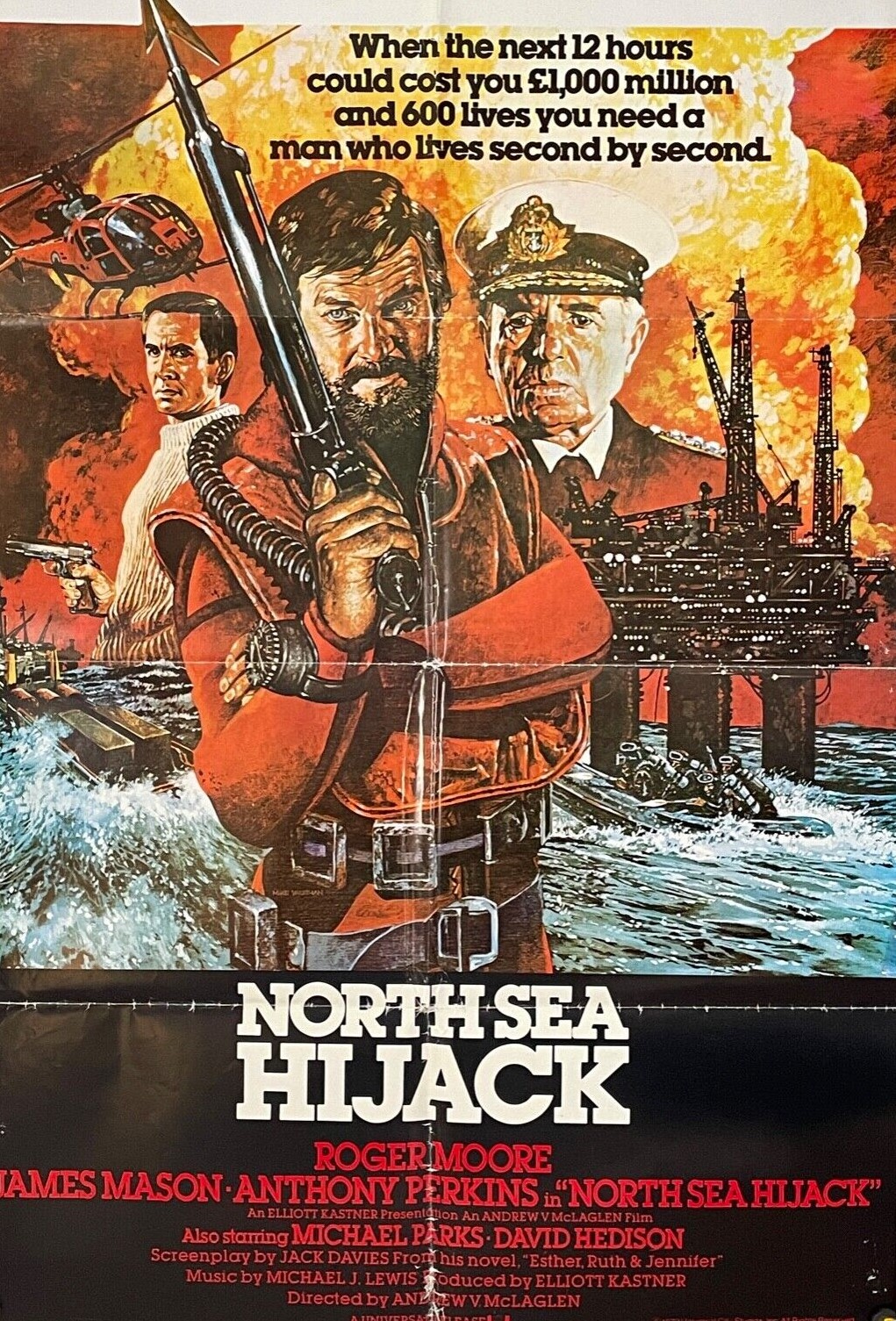

Young seems lacking in the stiff upper lip department, condemned for “misplaced chivatry,” unwilling to just do his job, and certainly not to blindly obey the more ruthless ignorant Stafford. Aware he is unable to stop what the British would like to call progress, hopes he can ease the transition, avoid driving the tribesmen into the ground and prevent a noble leader like Sultan ending up a despised bandit, the kind who were forever presented as the bad guys in films like North West Frontier / Flame over India (1959).

Young has the sense not to be dragged all over the country searching for his quarry, and sets up his team in more sensible fashion, but still, is largely outwitted by Sultan, especially as Stafford, who later gets in on the act, is too dumb to fall for obvious lures. Adding complication is the arrival of Stafford’s equally intelligent daughter Jane (Charlotte Rampling), a Cambridge University graduate, who falls for Young.

Thankfully, there’s no need for the British hero to transition from brute into someone more appreciative of the way of life he is forced to destroy – a trope in the American western – and equally there’s no corrupt businessman selling the tribesman weaponry and there’s no savage attack either on innocent women and children, and removal of these narrative cliches allows the movie more freedom to debate the central questions of freedom. The tribesmen acquire rifles and the occasional Gatling gun simply by stealing them from the more inept British soldiers.

Anyone expecting a shoot-out or more likely a swordfght between Sultan and Young will be disappointed, the title, as with the entire picture, is more subtle than that, especially as each, in turn, have the opportunity to save each other’s lives. Eventually, Young’s sympathetic approach is deemed ineffective and Stafford is put in charge, leading to a superb climax.

While Sultan’s nomadic lifestyle is eased by dancing girl Champa (Virginia North), whose loyalty to her lover is soon put to the test, and who is not, surprisingly, necessarily looking for love, his emotions center more around his younger son, whom he doesn’t want to grow up wearting the tag of bandit’s son. The solution to that problem seems a tad simplistic, but still seems to work.

With the feeling of western with splendid use of superb mountainous locales, and excellent widescreen, an astute script opts as much for intelligence as adventure.

One of Yul Brynner’s (The Double Man, 1967) last great roles before he turned into a parody of himself and certainly more than matched by Trevor Howard (Von Ryan’s Express, 1967), given a role with considerable depth and scope. Charlotte Rampling (Three, 1969) also impresses while Virginia North (Deadlier than the Male, 1967) and Imogen Hassall (El Condor, 1970) provide support. Harry Andrews (The Night They Raided Minsky’s / The Night They Invented Striptease, 1968) has played this role before. You can catch Edward Fox (Day of the Jackal, 1973) in a tiny role.

Superbly directed by Ken Annakin (Battle of the Bulge, 1965) from a script by Peter Yeldham (Age of Consent, 1969), Ernest Borneman (Game of Danger, 1954) and Ranveer Singh in his debut.

Well worth a look.