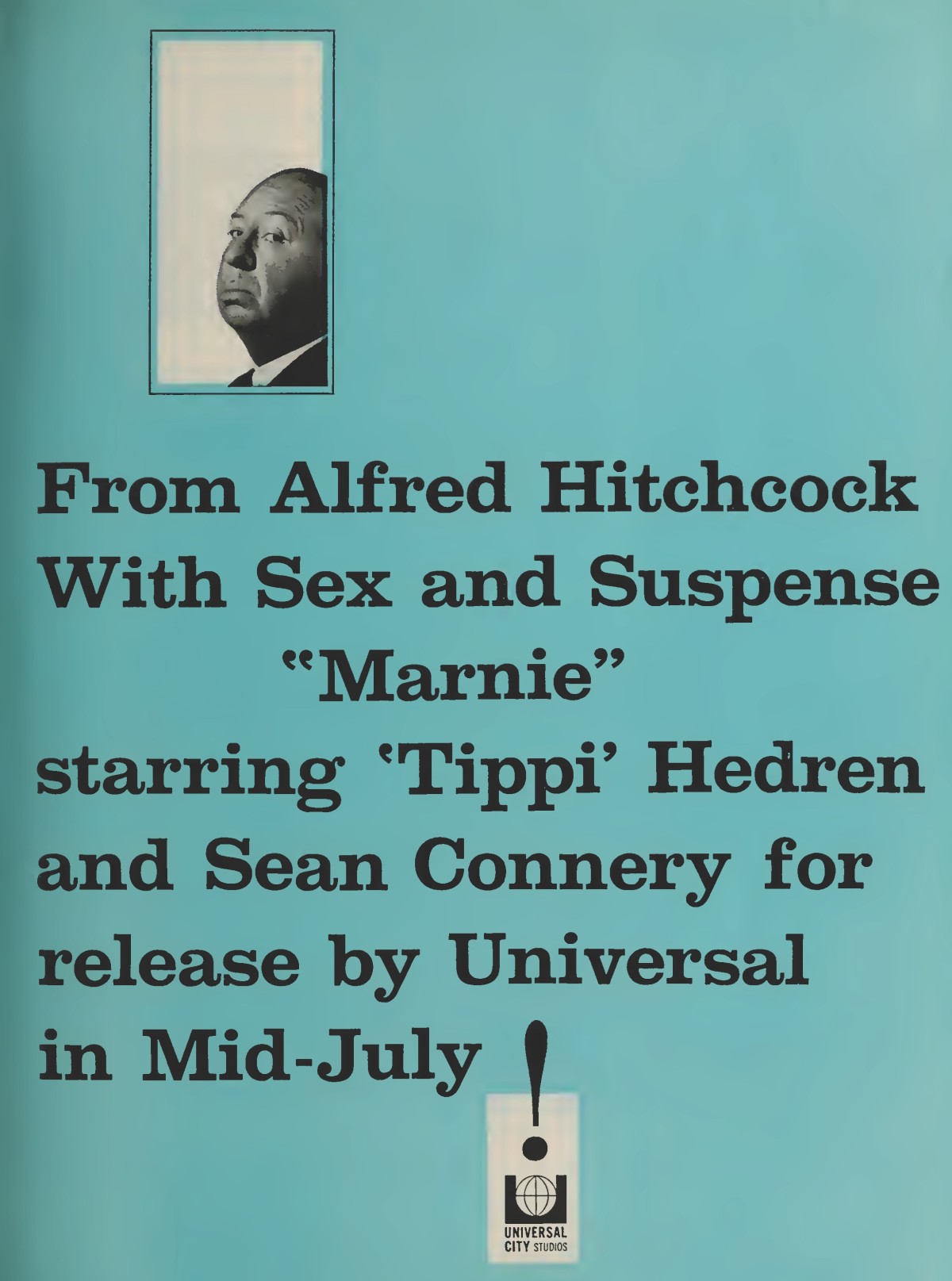

Alfred Hitchcock had a different picture – in fact, several movies – in mind as the follow-up to Psycho (1960), the biggest hit of his career. In pole position was Marnie to star Grace Kelly (“she voluntarily offered to do the picture after reading the story”), the woman he had made a star, in a sensational return to the screen after her marriage to Prince Rainier of Monaco. Her participation would bring her around $1 million. He worked on a script during 1961 but Kelly’s schedule meant the film would have to be postponed to 1963-1964 at the earliest.

A close second came No Bail for a Judge to star Audrey Hepburn. When those projects failed to get off the ground in the gap between Psycho and The Birds (1963), Hitchcock also considered reuniting with James Stewart (Vertigo, 1958) for Blind Man. The original idea came from a visit by the writer to Disneyland where he had an idea for a blind man given an eye transplant who subsequently remembers things he could not have witnessed. This was then transposed to an ocean liner, with Ernest Lehman signing on for script duties in December 1960. For almost a year he worked on a movie called Frenzy, no relation except for serial killing, to the later picture. But there was also Trap for a Solitary Man, Cold War thriller Village of Stars and The Mind Thing.

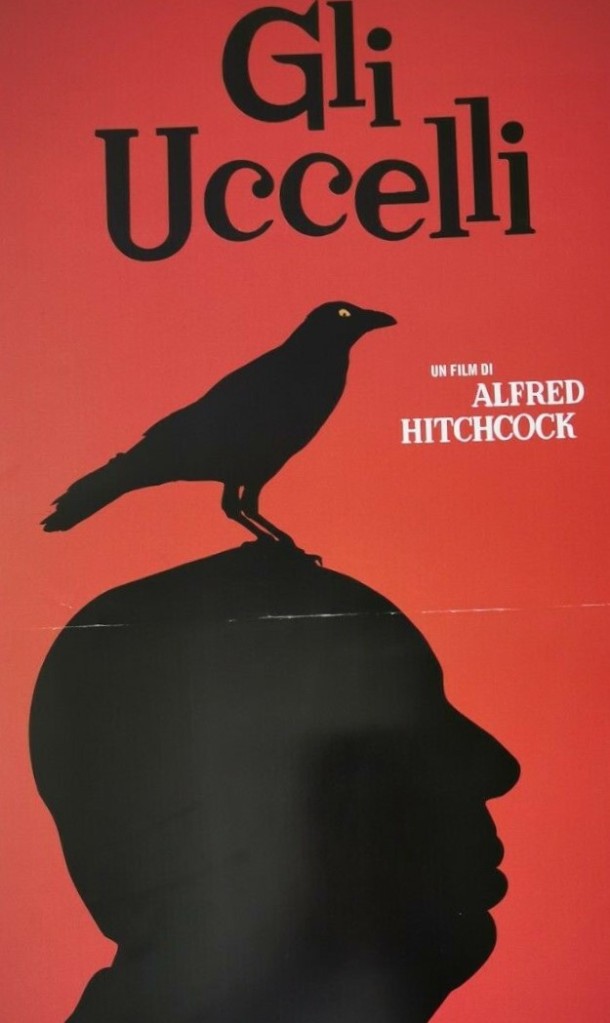

When Hitchcock finally settled on The Birds, based on a short story published in Good Housekeeping magazine in 1952 and reprinted in a Hitchcock anthology in 1959, he first turned to Scottish author James Kennaway (Tunes of Glory, 1960). That collaboration lasted until Kennaway decided the only way the movie would work would be if the birds were never seen. He considered Wendell Mayes (Von Ryan’s Express, 1965) and Ray Bradbury (The Picasso Summer, 1969) before in August 1961 turning to Evan Hunter (Last Summer, 1969). Wearing his Ed McBain (Fuzz, 1972) hat, Hunter was a crime aficionado so it was no surprise he suggested adding a murder to the mix.

But Hitchcock’s first act was to shift the location from Cornwall to Bodega Bay, sixty miles away from San Francisco. While the screenplay was being worked upon, an extensive proce3ss that would include last-minute changes once filming had begun, Hitchcock considered a potential female star.

He screen-tested Pamela Tiffin (One, Two, Three, 1961) and examined footage featuring Yvette Mimieux (The Time Machine, 1960), Carol Lynley (Return to Peyton Place, 1961) and Sandra Dee (Tammy Tell Me True, 1961). He also considered two actresses he already had under contract Joanna Moore (Walk on the Wild Side, 1962) and Claire Griswold (Experiment in Terror, 1962).

Both the women already under contract had proved disappointing. Of Moore, John Russell Taylor wrote: “no one could have been less cooperative in the required making-over process, she did not like the clothes, she did not like the hair styles and she did not seem to like anyone she came into contact with at the studio.” Griswold, more compliant, “seemed to have little professional ambition and was quite content with what she was, Mrs Sydney Pollack.”

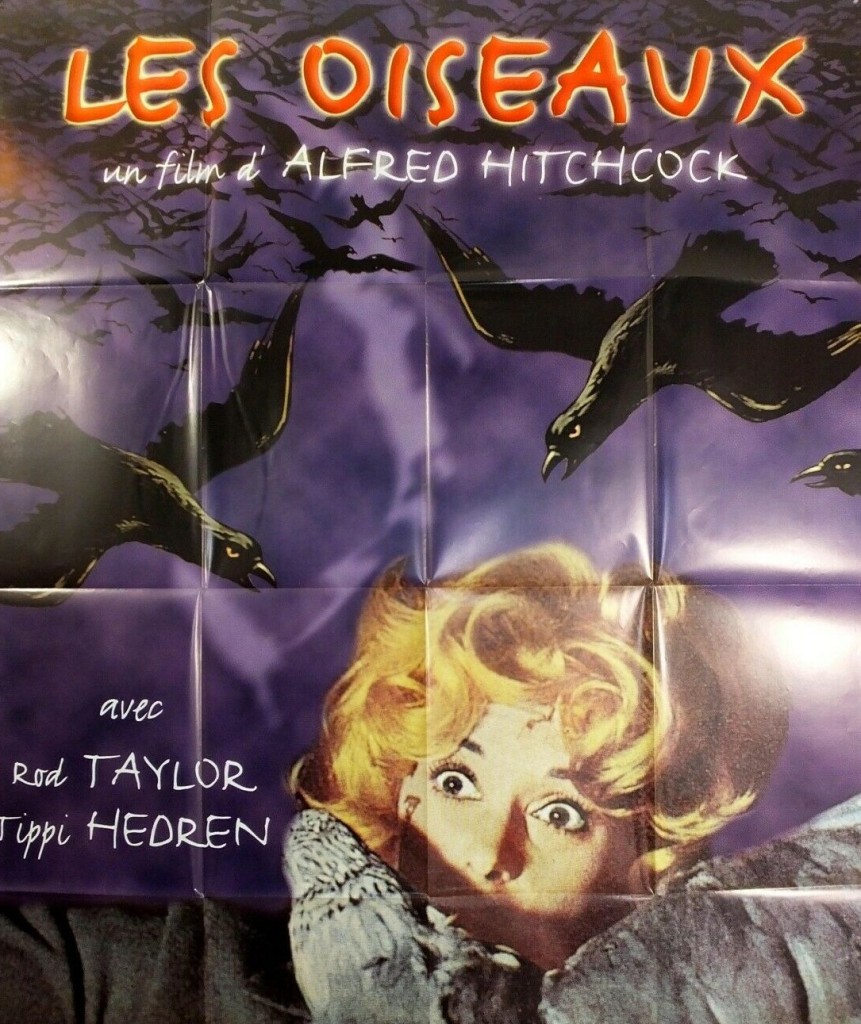

But then he spotted model Tippi Hedren in a television commercial. She was signed up to a seven-year $26,000-a-year ($254,000 at current prices) contract before she even met Hitchcock, one of the director’s modus operandi to ensure fees did not increase when his name was mentioned. Although actors, once successful, tended to complain they were hired at unfair salaries, this was in fact a pretty good amount for an untrained actress who would automatically become a star by the very fact of being in a Hitchcock picture. Of course, Hitchcock hoped to profit by keeping her salary low for any future movie. But it was still a gamble; if her career fizzled out, as did occur, he would lose out.

However, given his reputation for treating actors as cattle and expecting them to know what to do with little direction, he went to extreme pains to ensure Hedren was prepared for the role. He encouraged her to sit in on script conferences, meetings with set designers, and other essential collaborations like the director pf photography and the music supervisor and went into considerable detail about her motivation and how the film would move from periods of intensity to relaxation. Nobody ever received a more complete education in the Hitchcock method.

Hitchcock admitted he would have preferred to cast more experienced stars with guaranteed box office marquee such as Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn but the long shooting schedule and the time required for trick photography would render them too expensive.

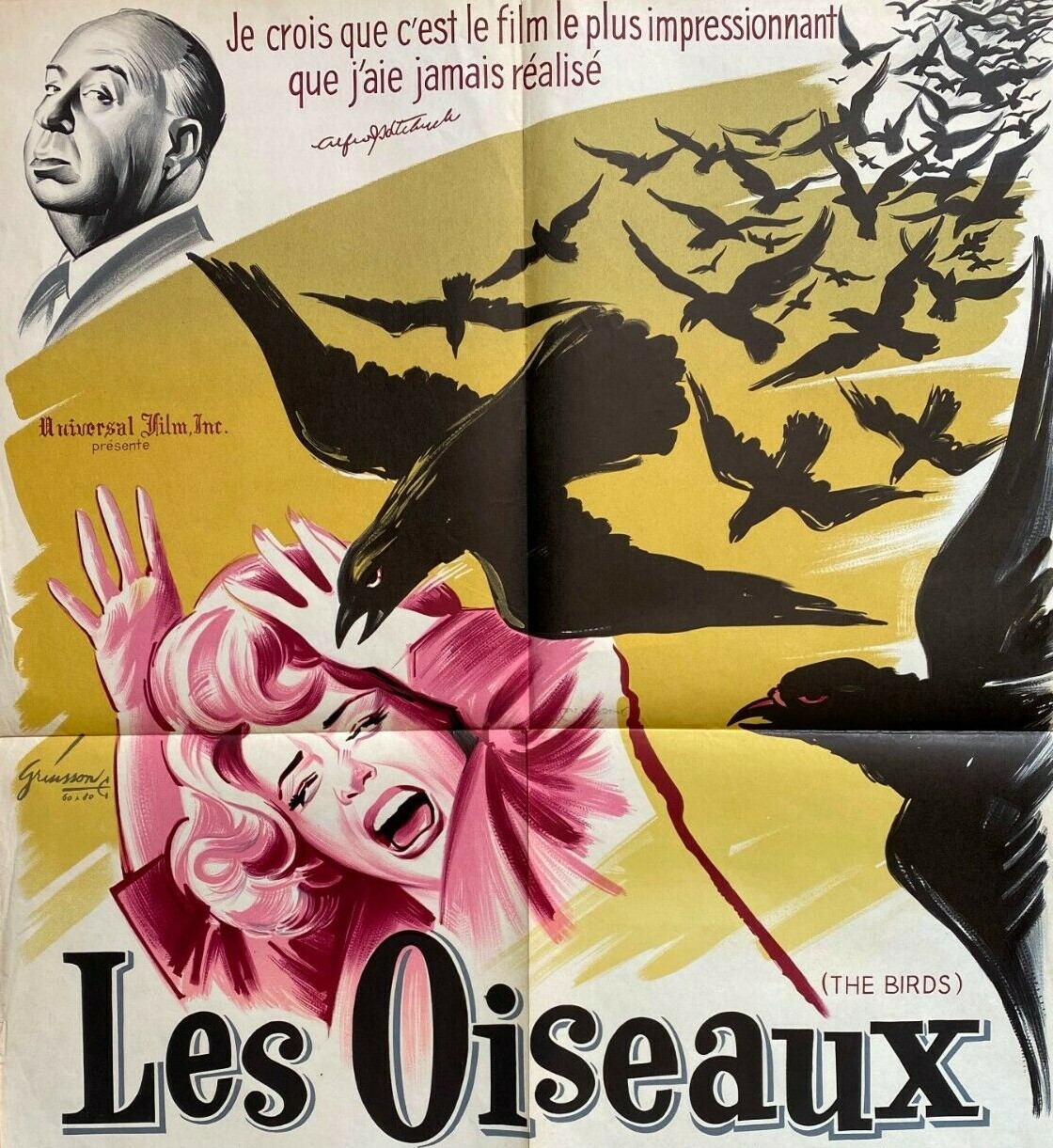

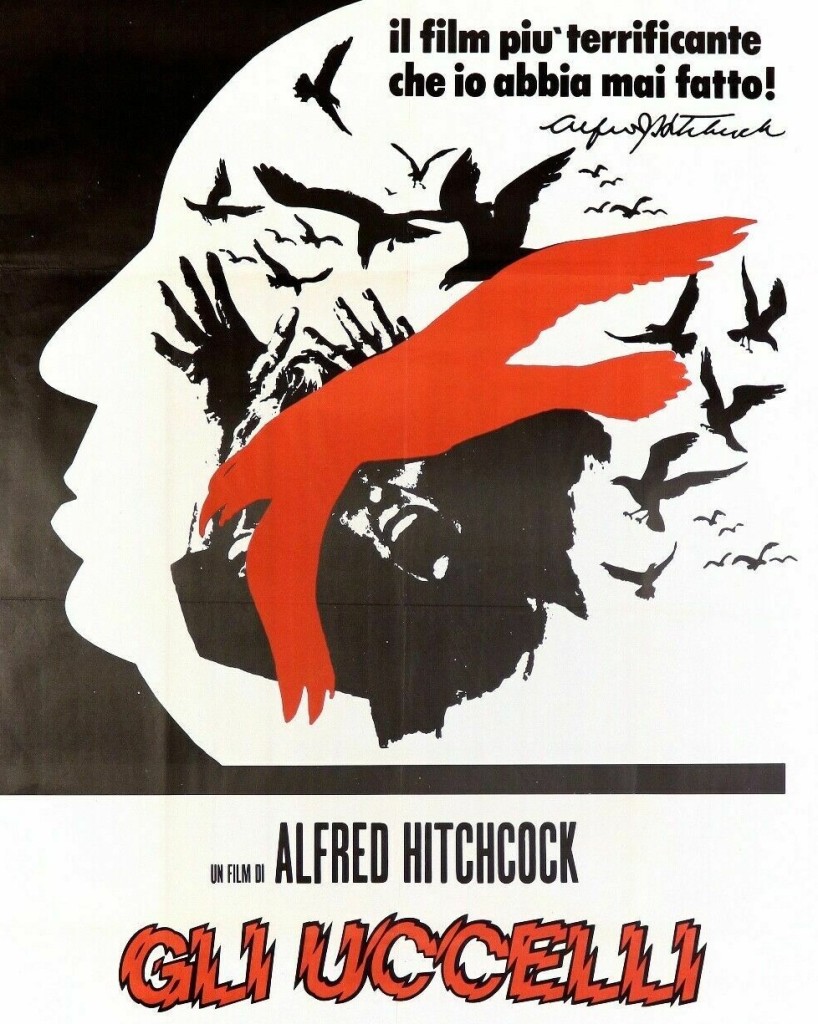

For this picture, Hitchcock switched studios from Paramount to Universal. At $3.3 million, very little going to the stars, this was his most expensive movie date especially in comparison to the $800,000 of Psycho. After a tortuous screenplay process, Hitchcock also sought input from others like famed short story writer V.S. Pritchett whose several notable suggestions the director accepted, much to the ire of Evan Hunter. According to Taylor, Hitchcock found himself “nervy and oppressed” possible due to the film’s Day of Judgement elements, and abandoned his normal shooting routine.

He was famous for shooting the picture he already had in his head. Instead, here “he started studying the scenario all over again while shooting it…(and) began to do something he never normally did – improvising on set.” He went deeper into characterizations – making the viewpoint far more subjective than initially conceived, in particular “keeping the audience much closer to the Tippi Hedren character”

At the last minute he dropped several pages of dialogue and the original Hunter ending. He edited out a love scene between Hedren and Taylor and detailed a script for the sound, specifying what kind he wanted for every scene. While Bernard Herrmann was involved, it wasn’t in the usual sense, and instead they worked out musical scenario of “evocative sound and silence” which was created by Remi Gassman and Oskar Sala who specialized in electronic music.

It was by far the most complicated shoot Hitchcock had ever attempted. The birds were a mixture of trained birds, dummies and optical illusions. When the gull attacked Hedren as the boat docks that was a dummy on a wire pulley, the blood a pellet implanted on her clothes. But as filming intensified, the blood seen on the screen was real blood. Anchovies and ground meat were spread on the actors’ hands at attract the gulls.

But when it came time to shoot the scene in the attic Hedren was not warned the birds would be real. Hitchcock believed terror would be better expressed by an untrained actress if it was real. While propmen wore thick leather gloves to protect their skin, the actress was permitted no such luxury. When the birds avoided Hedren, the propmen simply picked them up and threw them at the actress. Filming took a week, by the end of which, after getting her eye clawed, Hedren broke down in tears. It would be impossible for a director to take such liberties today although young, impressionistic actors tend to fall prey to such actions.

The proposed ending was jettisoned in favor of a lengthy shot of Hedren and co-star Rod Taylor driving through a bird-infested landscape that the director called the “single most difficult shot I’ve ever done.”

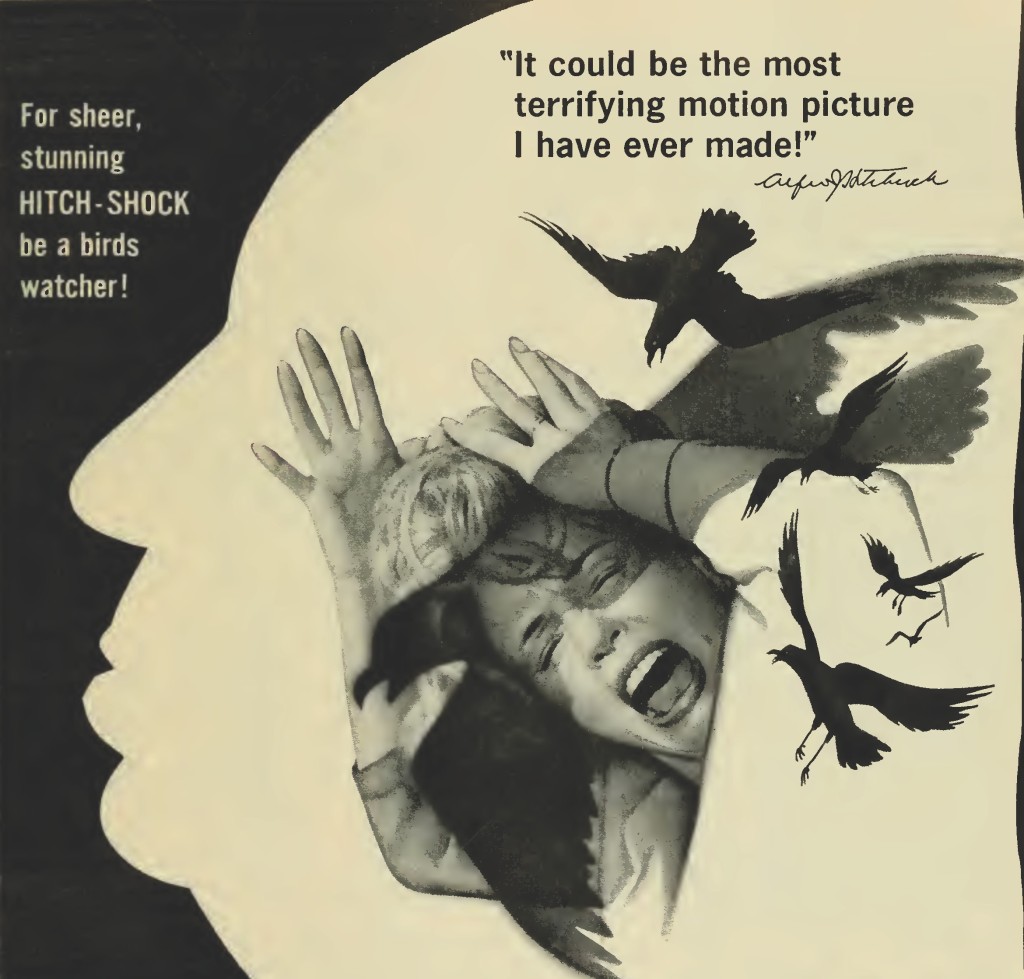

Hitchcock got into trouble with the authorities over unauthorized use of birds. His permit allowed for the use of 20 dead and 30 live birds but an investigation by the U.S. Wildlife and fisheries found 40 dead gulls and 54 live ones as well as 60 songbirds for which no license had been given. He was fined $400. The movie was of course a boon for exhibitors planning promotional stunts. A thousand pigeons were released in a shopping center in Albany, carrier pigeons carried a message from Los Angeles to Memphis, birds trainers were in full flight, 200 exotic birds were displayed in the lobby of the Stanton in Baltimore, while the director attracted notoriety by making birds singular rather than plural when the tagline became “The Birds Is Here!

Much has been written of Hedren’s reactions to the birds, but it’s worth having a look at Roar (1981), a famous disaster of a picture, which she and husband Noel Marshall financed, where she appeared to be quite happy to be bitten and clawed by lions, a lot less tame than was suggested. The mauling was so bad Hedren required 50 stitches, required plastic surgery and nearly lost an eye. In one unscripted scene that ended up in the picture a lion grabbed her hair and would not let go. Most of the lion attacks resulted in injury to someone, actors and crew, including cinematographer Jan de Bont who required 120 stitches to sew his torn scalp back in place. By such standards, her treatment by Hitchcock was relatively tame.

SOURCES: Patrick McGilligan, Alfred Hitchcock, A Life in Darkness and Light (Regan Books, 2003), p608-629; John Russell Taylor, Hitch, The Authorised Biography (Faber and Faber, 1978) p262-270; Brian Hannan, Darkness Visible, Alfred Hitchcock’s Greatest Film (Baroliant, 2013); “Princess Grace’s Take Per Hitchy Estimate,” Box Office, April 4, 1962, p2; “Fine Hitchcock $400,” Box Office, April 18, 1962, p17; “Pigeons Blaze a Trail,” Box Office, April 8, 1963, pB3; “Pigeons for Birds,” Box Office, May 6, 1963, pB3; “The Birds Is Here,” Box Office, May 13, 1963, pA1; “Bad Girls Bird House,” Box Office, May 27, 1963, pA3.