In previous decades, box office outside of the U.S., while a growing part of the ancillary equation, only in very rare circumstances outscored domestic. The general expectation, in part due to tougher competition for screens and extra distribution costs, was on average studios could expect to earn about half of domestic revenues.

There was one obvious exemption to this rule. James Bond overseas blew all the competition out of the water. And so it proved in the early 1970s from an examination of United Artists books for the period. Live and Let Die (1973) was the standout performer, knocking up $27 million in rentals (the studio share of the overall box office gross) from foreign cinemas compared to $16.4 million at home. Diamonds Are Forever (1971) did equally well – $22 million abroad, $20 million domestic.

James Bond was such a cash cow that surprised no one. Last Tango in Paris (1973) was considered an anomaly, controversy stoked by UA four-walling the picture when it couldn’t find enough screens. It came in third in the foreign market league, adding $16 million to domestic $21 million.

What did take Hollywood’s breath away was how often under-performers – flops even – at the U.S. ticket wickets did gangbusters elsewhere. The biggest winner was the aptly-named Michael Winner, director of westerns Lawman (1971) and Chato’s Land (1972), hitman thriller The Mechanic (1972) and spy drama Scorpio (1973). Total American rentals a shade over $7 million, total foreign rentals three times as much a colossal $21.8 million.

There was hardly a greater example of the disparity between American audience tastes and the rest of the world. And it made Hollywood studios more adventurous when it came to choosing subject matter, and in backing stars, aware that they could make their investment back – and more – from foreign markets.

It was probably astonishing to any studio executive that Burt Lancaster – for over two decades a high-flying marquee name from action-oriented fare like The Crimson Pirate (1952) and controversial drama From Here to Eternity (1953) to his Oscar-winning turn as Elmer Gantry (1960) and hardnosed western The Professionals (1966) – had lost his domestic audience especially after he had fronted up disaster movie smash Airport (1970).

But Lancaster could only scrape up $1.35 million at home for Scorpio, $2.1 million for Lawman and $2.8 million for another western Valdez Is Coming. Scorpio was the biggest hit abroad, with a massive $7 million, over five times domestic, while Lawman shot up $3.2 million (50 per cent above domestic) and Valdez Is Coming $2.65 million.

Charles Bronson was another beneficiary of foreign largesse. The Mechanic, too, targeted $7 million abroad, nearly three times the domestic tally of $2.6 million. Chato’s Land (1972) only delivered $1.27 million in the U.S. but $4.6 million abroad.

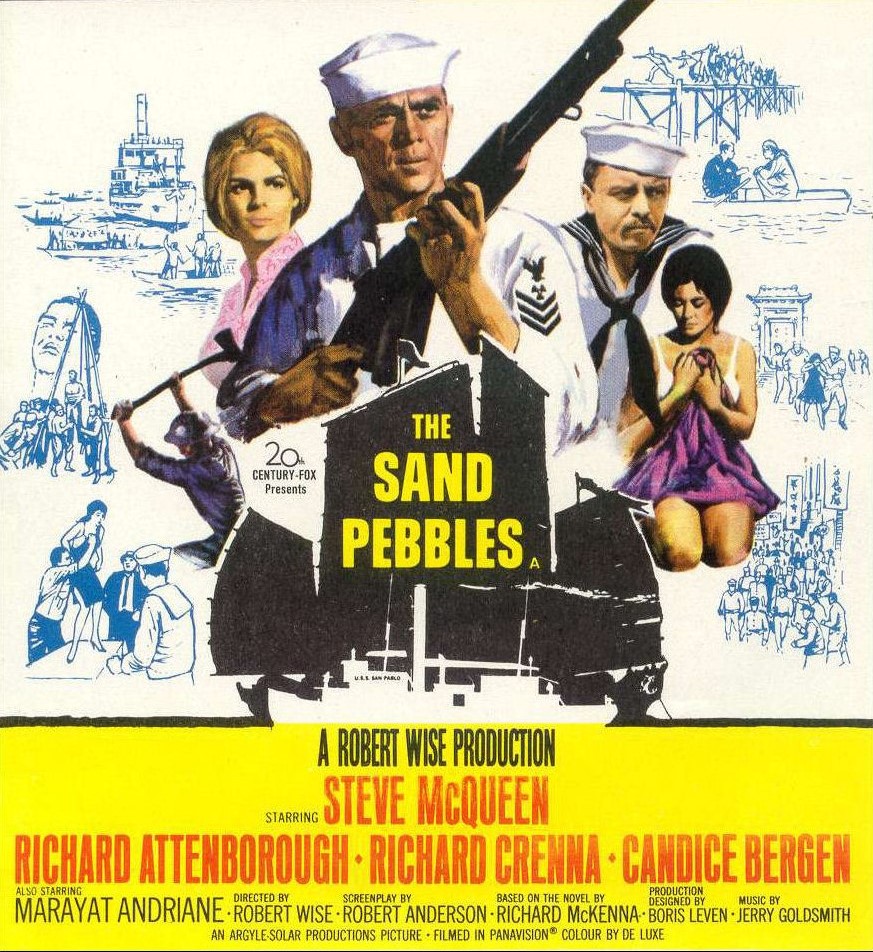

Westerns were a mixed bag. Oliver Reed-Candice Bergen-Gene Hackman number The Hunting Party (1971) was an almighty flop at home, just $800,000 in the kitty, but rallied somewhat abroad, not enough to turn profit but at least add a sheen of respectability, with $2.4 million elsewhere, three times domestic. The Magnificent Seven Ride! (1972), proof the sequels had outstayed their welcome, brought in just $750,000 domestically but again did triple the business abroad with $2.15 million and given the paltry budget enough to sit in the black.

Revisionist effort Billy Two Hats (1974) starring Gregory Peck added $900,000 abroad to a miserable $440,000 at home – foreign revenues not enough to save it from flop. But foreign couldn’t save the second remake of the Gunfight at the OK Corral legend, Doc (1971) with Stacy Keach and Faye Dunaway which moseyed along to $1.35 million abroad to add to $1.8 million domestic. And another western sequel Support Your Local Gunfighter (1971) notched up just $970,000 abroad compared to $2.1 million. Modern western The Honkers (1972) with James Coburn managed just $550,000 abroad and $1 million at home.

It didn’t really matter that Michael Caine comedy thriller Pulp (1972) did better abroad, figures everywhere nothing to write home about, $600,000 in total, five-sixths of that abroad. Fiddler on the Roof (1970), for other reasons, underwhelmed but nobody was going to complain too much when foreign audiences stuck $10 million in till, about a quarter of domestic.

There were some conundrums in the foreign-domestic share-out. Typically, American comedies didn’t travel. But Billy Wilder’s Avanti! (1972) starring Jack Lemmon, perhaps because of the Italian setting, did better abroad – $2.5 million to $1.6 million. Glenda Jackson British-made menage a trois Sunday, Bloody Sunday (1970) not surprisingly did better abroad, but only just, $1.8 million to $1.77 million.

Sidney Poitier in second sequel The Organization (1971) tapped into $2.9 million abroad and $2.45 million at home but generally too-specifically-American features struggled overseas, The Hospital (1971) snaring only $1.9 million compared to $9 million, White Lightning (1973) snagging $1.8 million compared to $6.9 million, Fuzz (1972) holstering $1.7 million against $3.1 million.