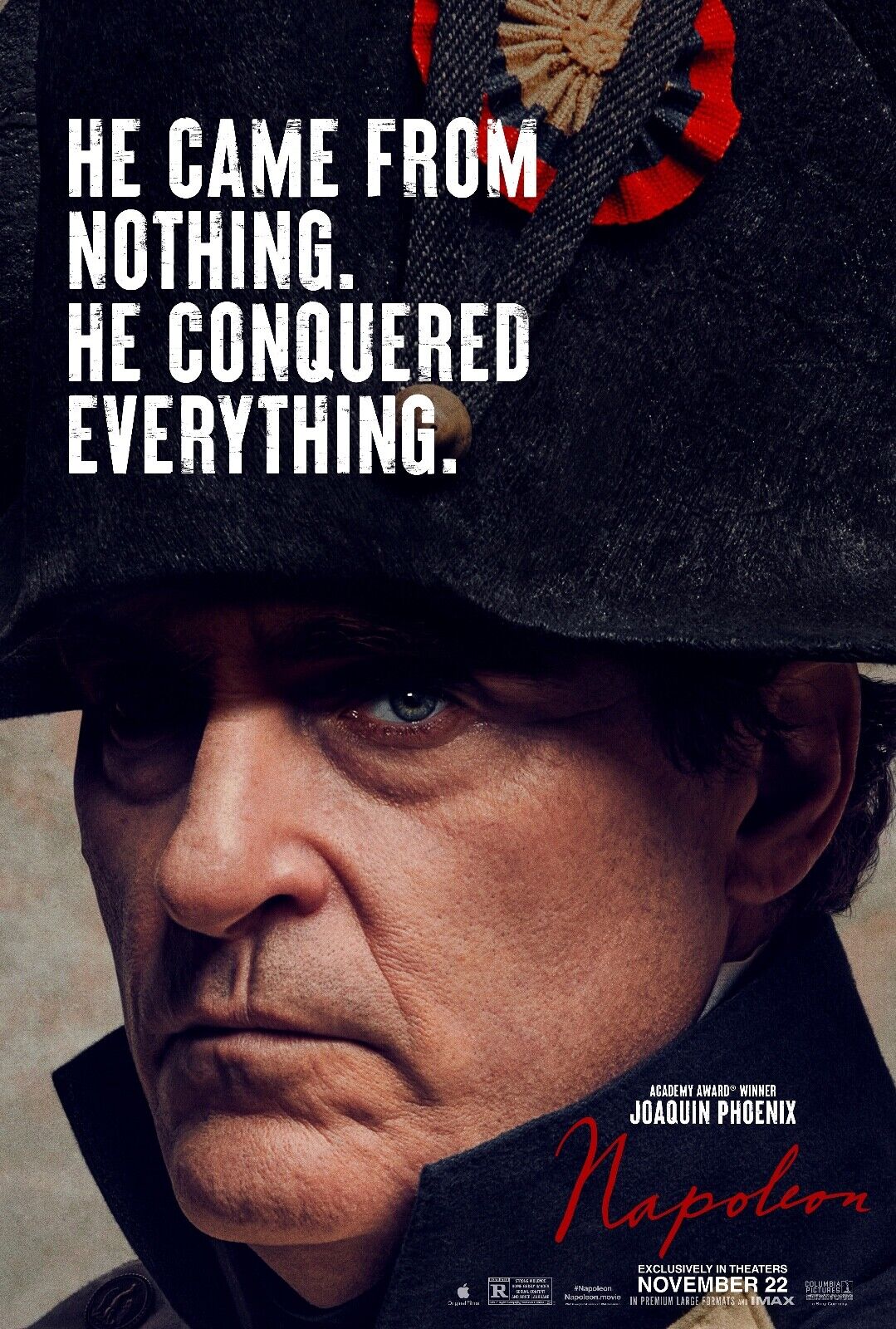

The makers of Oppenheimer (2023) and Napoleon (2023) cast light on the major problem of a biopic – what to leave out. Here, no such problem was actually countenanced. Hell, they just threw everything in – some job given the lean running time. That does mean, however, some mighty info dumps, as we are filled in on the gangster’s past and present. Not much of his life goes unturned.

There was a spate of gangster pictures around the turn of the decade. The success of Machine Gun Kelly (1958) starring Charles Bronson, The Bonnie Parker Story (1958) and Al Capone (1959) spurred a hot lead deluge the following year including Murder Inc (Lepke), Ma Barker’s Killer Brood, Pay or Die, The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond and Pretty Boy Floyd. In 1961 came Mad Dog Coll, Portrait of a Mobster (Dutch Schulz) and King of the Roaring 20s (Arnold Rothstein).

But if you thought this would lead to a noir revival, think again. Nobody would give finesse the time of day. Not with so many facts to pack in. And to explain – love of power and ambition the only psychological insight available – why of all the millions of Americans brought to their knees by the Great Depression Floyd was one of the few who turned to violent crime. His own saving grace – if it can be called that, given the length of the murder sheet – is his Robin Hood-ism, he gives way a lot of his stolen loot

We pick up Pretty Boy Floyd (John Ericson) towards the end of his short-lived boxing career – by which time he’s already been sent away for five years by Sheriff Blackie (Jason Evers), annoyed the gangster had taken up with his sister. Floyd now beats up the husband of his lover, works on the oil rigs but loses his job for concealing his criminal record. Returning to Oklahoma, he discovers his father has just been shot by a character called Grindon, who got away with the crime.

He tries to go straight but is turned down for a loan by the bank. He locates Grindon and ices him. Partnering with hood Shorty Walters (Peter Falk), he enters the bank-robbing business, but Shorty’s loud mouth gets them caught. On the way to prison, they escape and rob the bank that refused him a loan.

He heads for Kansas City because until the FBI came along you could commit a crime in one state and vanish over the border to another knowing you were out of the original jurisdiction and couldn’t be tracked down. He finds another married woman, Lil Courtney (Joan Harvey), to romance, but the husband wants to turn him in for the reward, by now substantial. Returning to Oklahoma and teaming up with the vulnerable childhood pal Curly (Carl York), he gets into his stride, robbing a bank every two weeks.

You get the picture. This is biopic at full throttle. Every “I” is dotted and every “t” is crossed and still we don’t get any real idea what made him tick beyond he was as mad as hell and wasn’t going to take it anymore. I could have got all of this from a book.

The one ace fact I learned was where the term “kiss of death” comes from. Apparently, if you committed a crime against the mob – such as killing someone you were paid to rescue – you were put on trial before three Mob guys. The verdict had to be unanimous and was decided thus: a gun was passed between the three men, if each of them picked up the pistol and kissed it you were a dead duck.

The problem with all the gangster pictures is they all end the same way. Nobody is long for this world and nobody can evade justice.

This is straightforward stuff, shot on a tiny budget, and except for the info dumps and pausing here and there for a spot of philosophy/psychology or sympathy, tears along at a fair old pace. That’s very much on the plus side. On the minus side is the lack of depth and you would have to say lack of acting.

It’s not much of a stretch for John Ericson (The Money Jungle, 1967) to look mean, but he’s closer to James Dean than Charles Bronson. Peter Falk (Machine Gun McCain, 1969) is generally perceived as the standout but my money is on Barry Newman (Vanishing Point, 1970) as Floyd’s trainer and later criminal partner. Shame Joan Harvey (Hand of Night, 1962) only made three pictures, as she excels in a small part.

The whizz-bang approach from writer-director Herbert J. Leder (It!, 1967) ensures that, like Napoleon, you need Google open to check out the flood of names racing towards you. You might be baffled and confused, but never bored.

Worth it for the “kiss of death.”