It’s a been a fabulous year for watching the movies and my pictures of the year (the first full year of the Blog running from July to June, I hasten to add) make up an eclectic collection ranging from historical epics, dramas and westerns to horror, thrillers and comedy. Although this is my chosen decade, many of the films I was seeing for the first time so it was interesting to sometimes come at a film that had not necessarily received kind reviews and discover for one reason or another cinematic gems. There was no single reason why these pictures were chosen. Sometimes it was the performance, sometimes the direction, sometimes a combination of both.

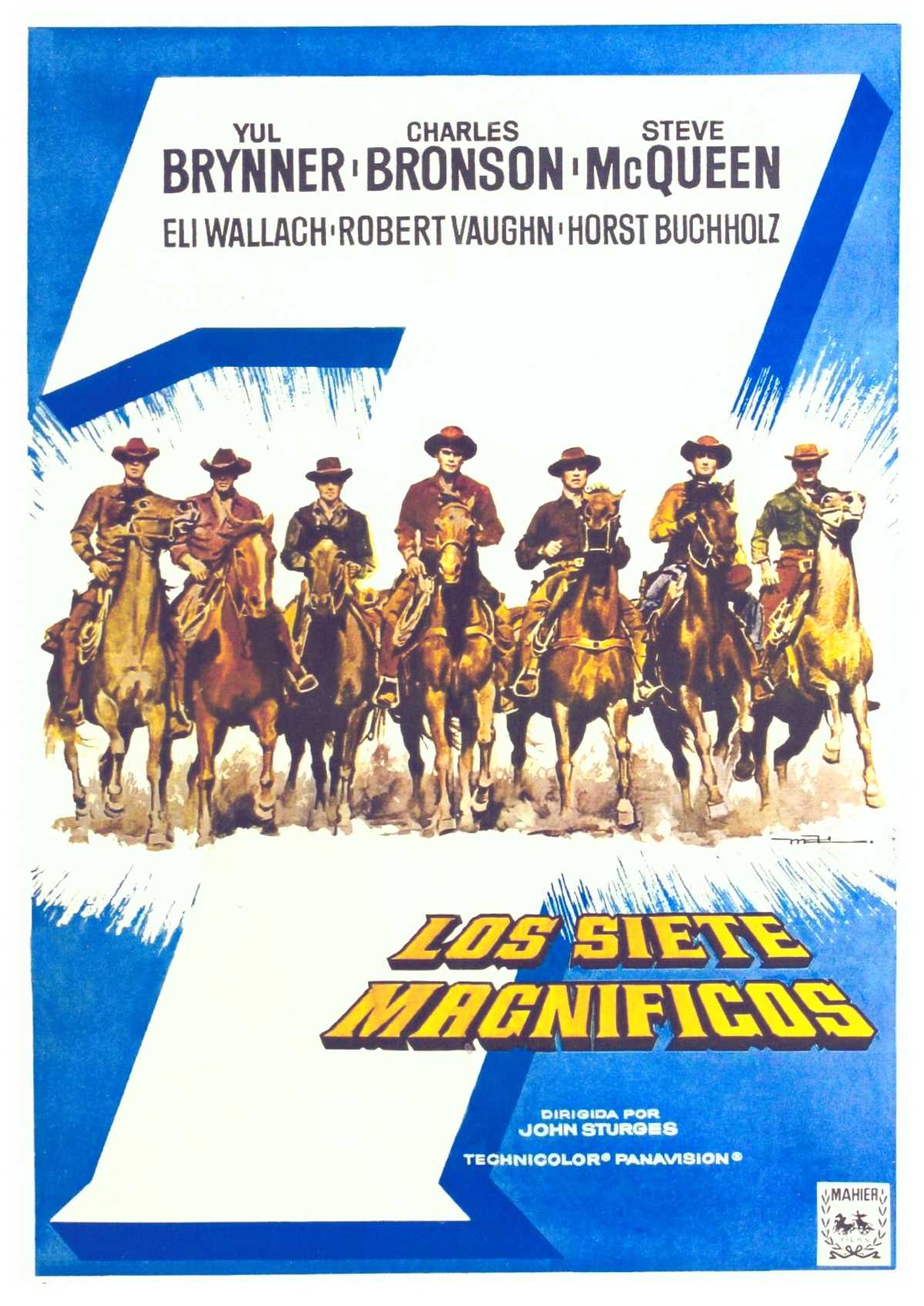

The westerns I most enjoyed came from either ends of the decade – John Wayne and Rock Hudson in magnificent widescreen spectacle The Undefeated (1969) and Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, James Coburn and the team in The Magnificent Seven (1960).

There was another ensemble all-star cast in J. Lee Thompson war film The Guns of Navarone (1961) one of the biggest hits of the decade with Gregory Peck, Anthony Quinn, David Niven, Stanley Baker et al.

Horror brought a couple of surprises in the shape of Daliah Lavi as the Italian peasant succumbing to The Demon (1963) and Peter Cushing menaced by The Skull (1965).

Not surprisingly perhaps Alfred Hitchcock headed the ranks of the five-star thrillers, but surprisingly to some, this was in the shape of Marnie (1964) with Sean Connery and Tippi Hedren rather than some of his decade’s more famous / infamous productions. Heading the romantic thrillers was the terrifically twisty Blindfold (1965) with Rock Hudson and Claudia Cardinale teaming up to find a missing scientist. The Sicilian Clan (1969) proved to be a fine heist picture in its own right as well as a precursor to The Godfather with a topline French cast in Alain Delon, Lino Ventura and Jean Gabin.

Only one comedy made the five-star grade and what else would you expect from Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (1959), slightly outside my chosen remit of films from the 1960s, but impossible to ignore the chance to see Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon strutting their stuff on the big screen. For the same reason I had the opportunity to re-evaluate Ridley Scott’s Oscar-winning historical epic The Gladiator (2000) that gave Hollywood a new action hero in Russell Crowe. Stylish contemporary sci-fi chiller Possessor (2000), from Brandon Cronenberg, was another one seen on the big screen, one of the few in this year of the pandemic.

Most people would certainly put Paul Newman as prisoner Cool Hand Luke (1967) in this elevated category but, to my surprise, I found several other dramas fitted the bill. The clever sexy love triangle Les Biches (1968) from French director Claude Chabrol made his name. Burt Lancaster turned in a superlative and under-rated performance in the heart-breaking The Swimmer (1968) about the loss of the American Dream. Rod Steiger, on the other hand, was a hair’s-breadth away from picking up an Oscar for his repressed turn as The Pawnbroker (1964).

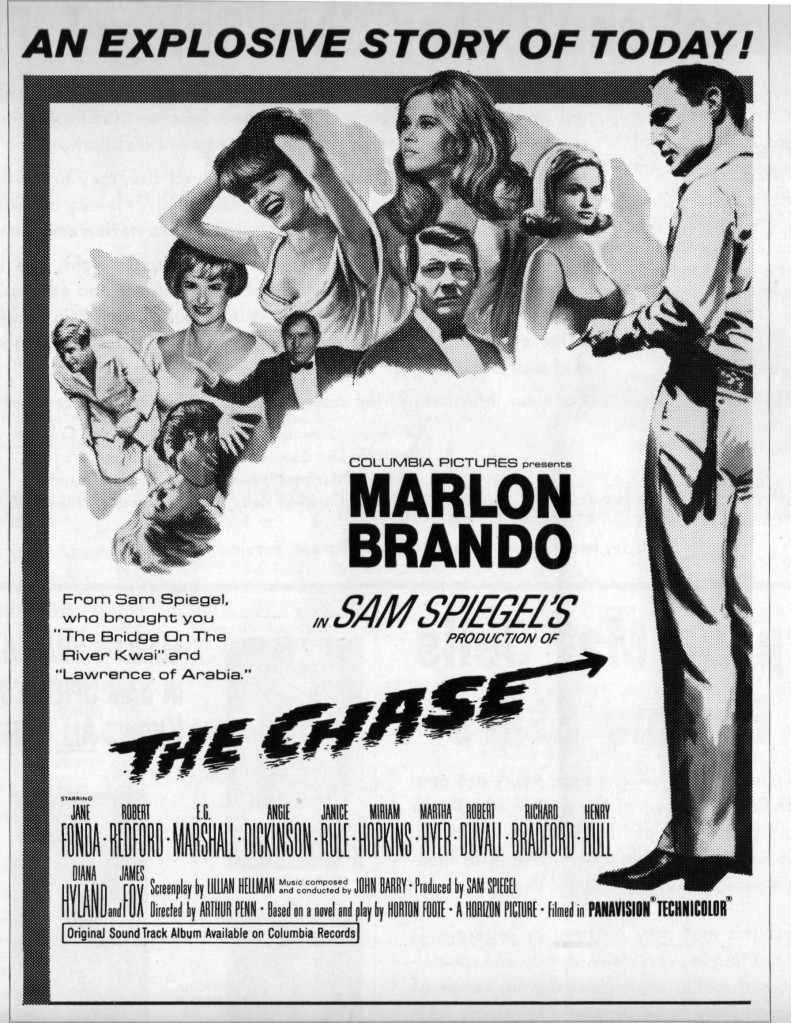

Two films set in the Deep South also made the list – Marlon Brando in Arthur Penn’s depiction of racism in small-town America in The Chase (1966) with an amazing cast also featuring Jane Fonda and Robert Redford, and Michael Caine as a more than passable arrogant southerner in Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown (1967) opposite rising star Faye Dunaway. Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda’s hymn to the freedom of the motorbike in Easy Rider (1969) turned into a tragic study of attitudes to non-conformity.

For only eighteen films out of a possible two hundred to make the cut indicates the high standards set, and I am looking forward to as many, if not more, brilliant films in the year to come.