Pop quiz: name the only brother and sister who appeared in the same James Bond film. Hint: You Only Live Twice (1967). You might be more familiar with Tsai Chin (The Face of Fu Manchu, 1965, and three sequels) than Michael Chow. Though he had a bigger role in Joanna (1969) and The Touchables (1969) he was never more than a bit player, and often uncredited (55 Days at Peking, 1963). He also appeared in The Brides of Fu Manchu (1966) and there’s a fair chance you might remember him from Modesty Blaise (1966).

But HBO isn’t noted for devoting a documentary to a bit part player, not even one who can recite the opening of any film you care to mention. This film begins with such a recitation – encompassing the likes of North by Northwest (1959). If ever there was a more arresting opening to a documentary, this is it.

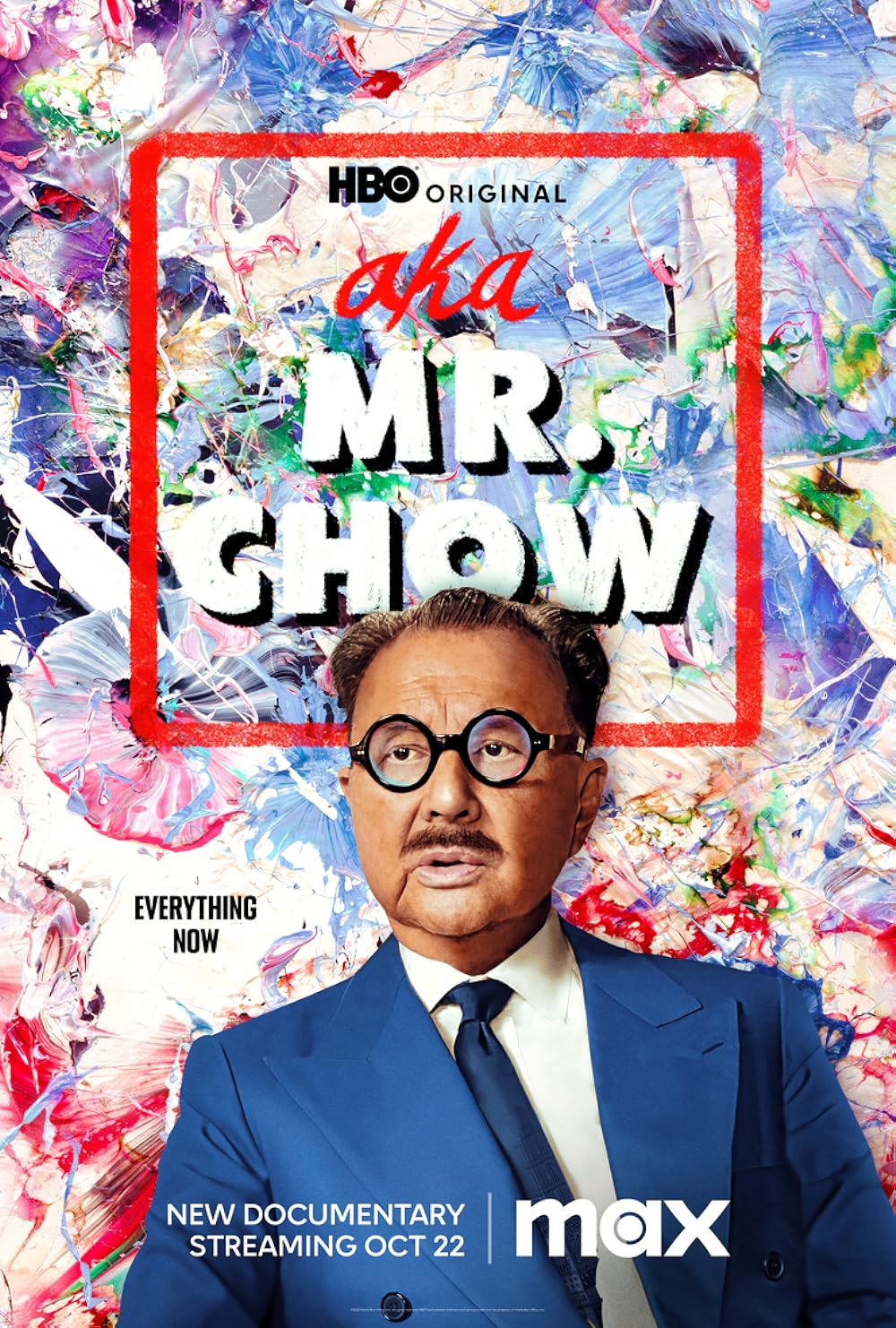

If you’re a fashionista or restaurant fan or gulled by celebrity photos, you’ll more likely know him by the name of Mr Chow, under which he established a chain of spectacularly successful eateries in London, New York and Los Angeles. He wasn’t even a chef, an understandable subject for a docu, what with all the creative endeavor that involves. But there’s no doubt he was creative, if only in reinventing himself. Born Zhou Yinghun, he chose the name “Mr Chow” because it meant people addressing him such manner rather than treating him with a racist epithet.

He might well have deserved a documentary for other reasons. He was the son of one of most famous Chinese opera stars, who reinvented the genre, and he escaped the cull of the intelligentsia instigated by Chairman Mao. His father was imprisoned for years and his mother was “beaten to death.”

The young Chow was living in England at his point, having been sent at a young age to a boarding school there, where racism of course was endemic. He attended art school but when his paintings didn’t sell he made a living from bit parts in movies – he was the child mown down by a car in Violent Saturday (1960), for example.

A Chinaman wanting to set up a business in London in the 1960s had two options: a laundry or a restaurant. But Chow didn’t want to imitate the ubiquitous Chinese restaurant. His artistic side came to the fore via interior design. His venture, in the staid world of the restaurants of the era, was a culture shock. Everything about it was different – no chopsticks and Italian waiters and no dressing for dinner (wear what you like), an anomaly in a high-end operation at the time. But since he attracted more than his fair share of celebrities presumably what they wore was highly acceptable.

An abundance of charm and connections gained through the movie business provided the funding. But it soon became the “in” place, and every evening was a performance.

By the time HBO came to make a documentary about him – and perhaps this fitted in more with that streamer’s agenda – he had become a proper artist. So much of the film, and indeed a good chunk of the opening section, is devoted to his modernistic artworks which often involved blowtorches, sheets of plastic and a rubber hammer. He exhibits under the name “M” so if you are familiar with the art world that might strike a better chord.

In the fashion of the current docu style, the makers seduce you with interesting material then hit you with a couple of blows you didn’t see coming. The “Shanghai trouble” is one such, which saw both parents killed. But there was also AIDS. His third wife Tina, a famous model, divorced at the time, died of that disease, contracted through a lover, not Chow, and she was one of the first non-homosexual people to be linked with the illness, and one of the first celebrities.

Abandoned, as he saw it, by his mother (in sending him to boarding school) family meant everything and you get the sense that the restaurants were as important as the various wives in creating a loving world. But he is also quite matter-of-fact about the personal calamities – you move on is his doctrine. The racism he endured cut deeper. Even as a famed restaurateur standing outside one of his own restaurants he found it hard to get a taxi to stop.

A handful of celebrities – hardly an all-star cast – pay tribute from Oscar-winning producer Brian Glazer (A Beautiful Mind, 2001) to LL Cool J and author Fran Lebowitz. But the pictures tell a story – Jack Nicholson, Mick Jagger etc are caught on camera having fun. I have to say the one time I went to the LA branch – as the guest of the publisher of Variety magazine – there was not a celebrity in sight (but it was lunch not dinner), though we were seated at Table No 1.

Cunningly directed by Nick Hooker (Agnelli, 2017).

As fascinating a docu as you will come across.