Restraint in a horror picture? Nary a scream? Scarcely a close up? More bloodletting in surgery than in the woods? Use of candlelight evocative of Stanley Kubrick? The classical composition of John Ford, long shot beloved of Henry Hathaway, in camera (minus the juddering cuts) treatment favored by Christopher Nolan? Where has this little gem been hiding?

Set in rural France in the nineteenth century, positing a Biblical reimagining of the werewolf legend, every scene so carefully measured by British director Sean Ellis (Anthropoid, 2016) that you would think this is a master sprung to life. Even more tantalizing, given the genre, is the ensemble acting. This isn’t one of those horror efforts where you’re trying to work out (or hope) who’s going to be bumped off next.

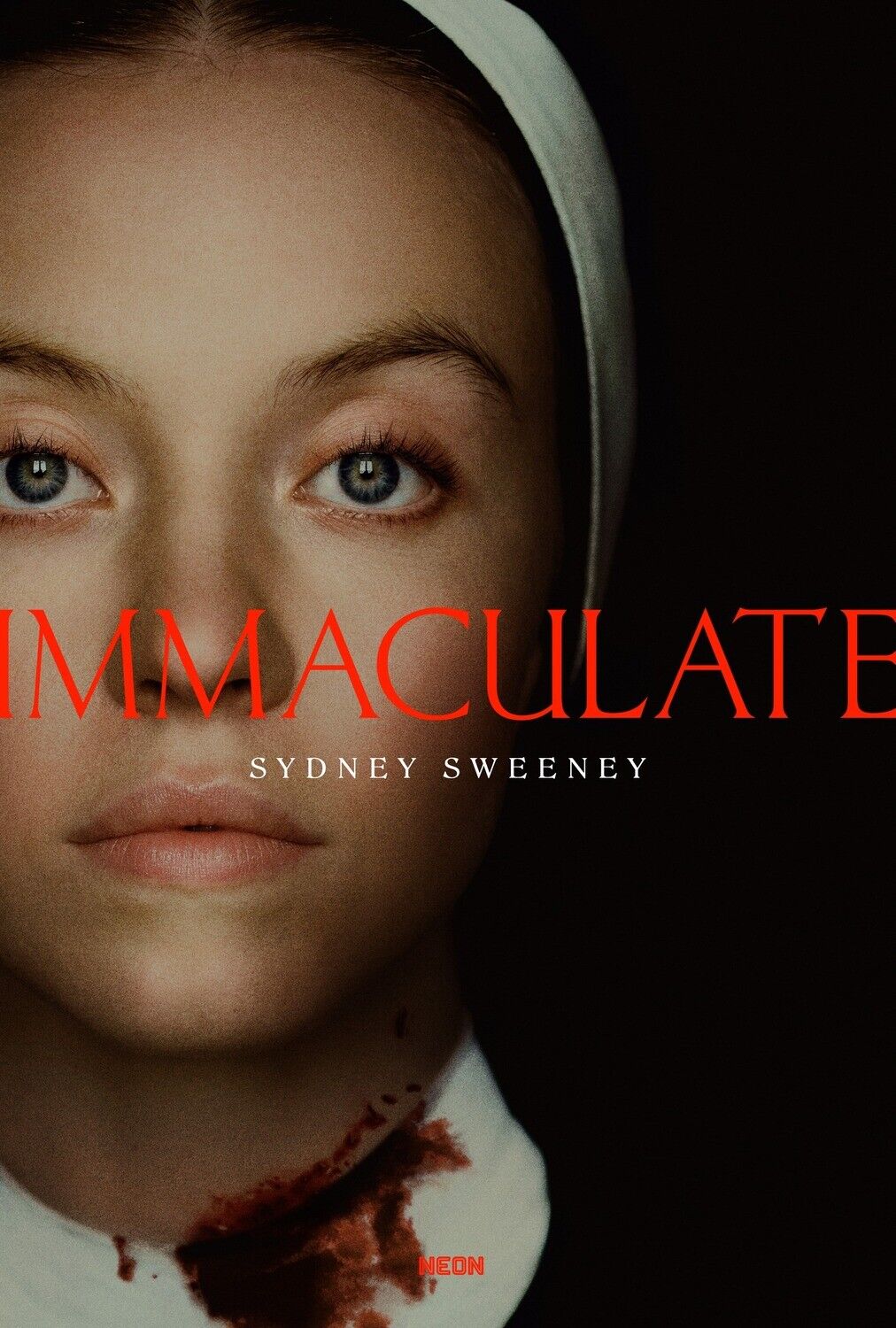

And you think – although the participants remain baffled – that you know what’s going on, so you let down your guard, until the feet are swept out beneath you by the late twist, that, too, with Biblical connotation. The first Biblical allusion seems far-fetched, I have to admit, linking Judas Iscariot’s 30 pieces of silver to the silver bullet traditionally used to kill werewolves, vampires and the like. But then it twists into left field, both thematically and intellectually, covering such wider ground as betrayal and confession. The second Biblical reference we are all familiar with – reaping what you sow.

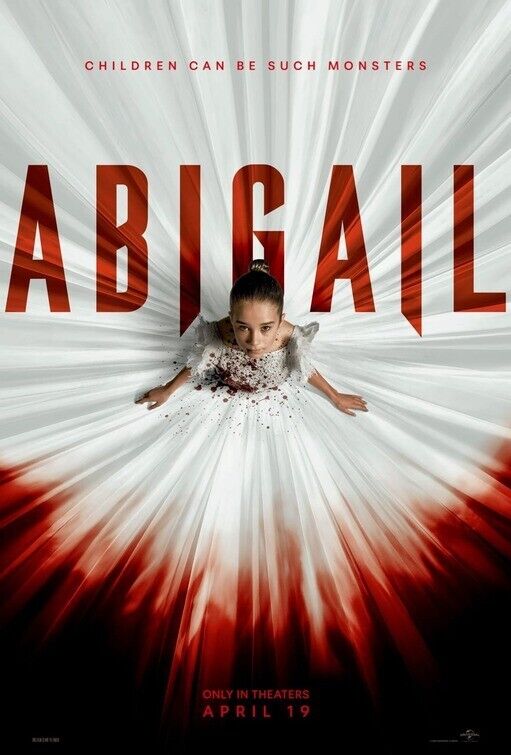

Technically, the narrative revolves around a gypsy curse. Nothing unusual in that you might think. Gypsies – and teenagers for that matter – are known for handing out curses for any minor breach or discrepancy. In this case, you wonder how the curse was set, given every single gypsy within the vicinity has been slaughtered, buried alive or, hands and feet chopped off, turned into a human scarecrow.

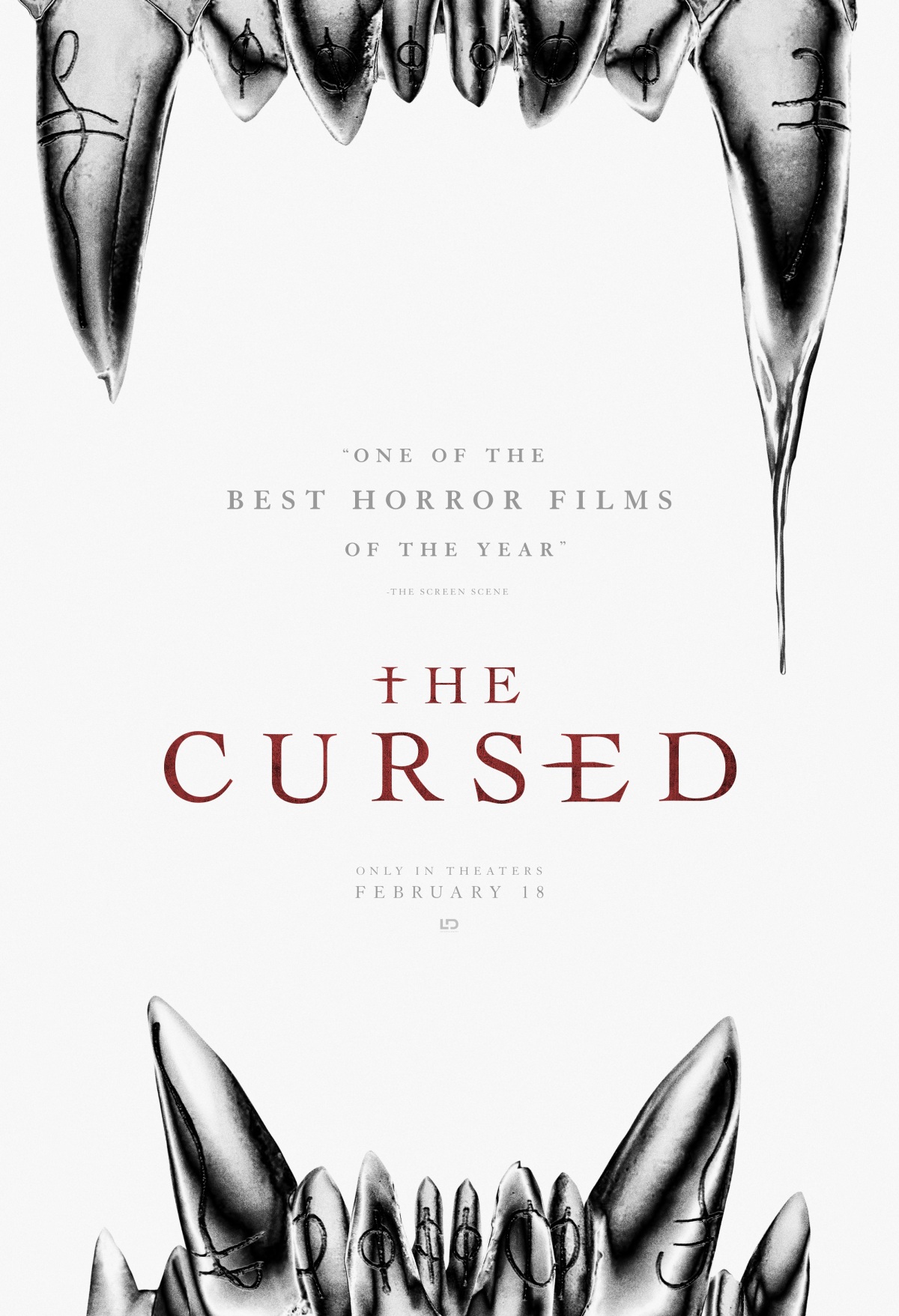

But the gypsies, suspecting imminent malevolence, have fashioned from their horde of silver coins (maybe thirty, we are not told), a pair of silver false teeth, which are buried, but then found by the local children, directed to them by dream/nightmare. These aren’t of the distinct vampiric molar kind, but seemingly more akin to those employed by wolves for savaging purposes. It’s the children who are turned into werewolves or, as here, that rarer mythical entity shamans (though not in the strict understanding of the word).

Victims appear chosen at random, and not for illicit sexual behaviour as was once the norm, and gradually a more apparent truth emerges. Eventually pathologist McBride (Boyd Holbrook) takes center stage, but that’s a slow time coming, and mostly what we have is nobody taking center stage, or focus shifting around a variety of characters, landowner Seamus (a traditional French name, don’t you know) Laurent (Alistair Petrie), submissive wife Isabelle (Kelly Reilly), their daughter Charlotte (Amelia Church) and a variety of young teenagers including Timmy (Tommy Rodger) and servants.

But, as I said, restraint is the watchword, and there are three just outstanding scenes. The movie opens – didn’t I mention this – in World War One, a field surgeon extracting bullets from a wounded soldier. The bullets don’t even, as would be the usual cliché, clang when tossed into a metal bowl. The surgeon finds two. The third is unusual. It’s much bigger for a start than your normal machine gun ammunition. And it’s silver.

And here’s the genius. Nobody exclaims, oh my goodness, a silver bullet, whatever can that mean, it just sits there dripping with blood from the operation, and the image filters down into the audience brain. Then we’re into flashback and gypsies making such a nuisance of themselves claiming ancient ownership of land that good old Seamus decides to call in the mercenaries. And that entire scene, of terrible slaughter, people shot and skewered and burned alive, is shown in extreme long shot, the camera never moving.

Third terrific scene. The Laurent’s son Edward is missing. Father, mother and daughter sit at the kind of long table you get in mansions, mother at one end father at the other. Mother is weeping scopiously, father is silently eating his dinner. Long shot again, no cuts, just the measured camera.

Virtually the only color in most scenes is a candle or a torch, and you would have to say a less showy and more effective treatment of light than in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975). And in audio terms it’s the same, scarcely a raised voice. And when McBride’s family tragedy is revealed, it’s done so visually and discreetly, though for the dumber audience member the ground is covered with dialog later on.

No showboating required from the actors so in that sense it’s the very best type of acting, as if everyone had learned from Anthony Hopkins how little you had to do to be effective. So top marks to Boyd Holbrook (Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, 2023), Kelly Reilly (Yellowstone, 2018-2022) and Alistair Petrie (Rogue One, 2016). Sean Ellis didn’t just write and direct this but he handled the cinematography too. Had this been an arthouse number, Ellis would be praised to the skies.

If you require jump-out-of-your-seat moments and copious gore, then this isn’t one for you, but if you want to appreciate a story superbly told by a director in command of his craft, then seek this out. Strangest of all it’s turned up on Netflix, not known for harvesting little gems, and probably scarcely aware of what it has uncovered.

A marvellous surprise.