Regular readers will know that this blog occasionally turns its attention to what comes under the generic title of “Other Stuff.” In the main and still covering movies I’ve reviewed this comprises behind the scenes looks at movies, examines pressbooks or marketing materials and analyses how books were shaped into films. I also focus from time to time on important issues that shaped Hollywood in the 1960s and write book reviews.

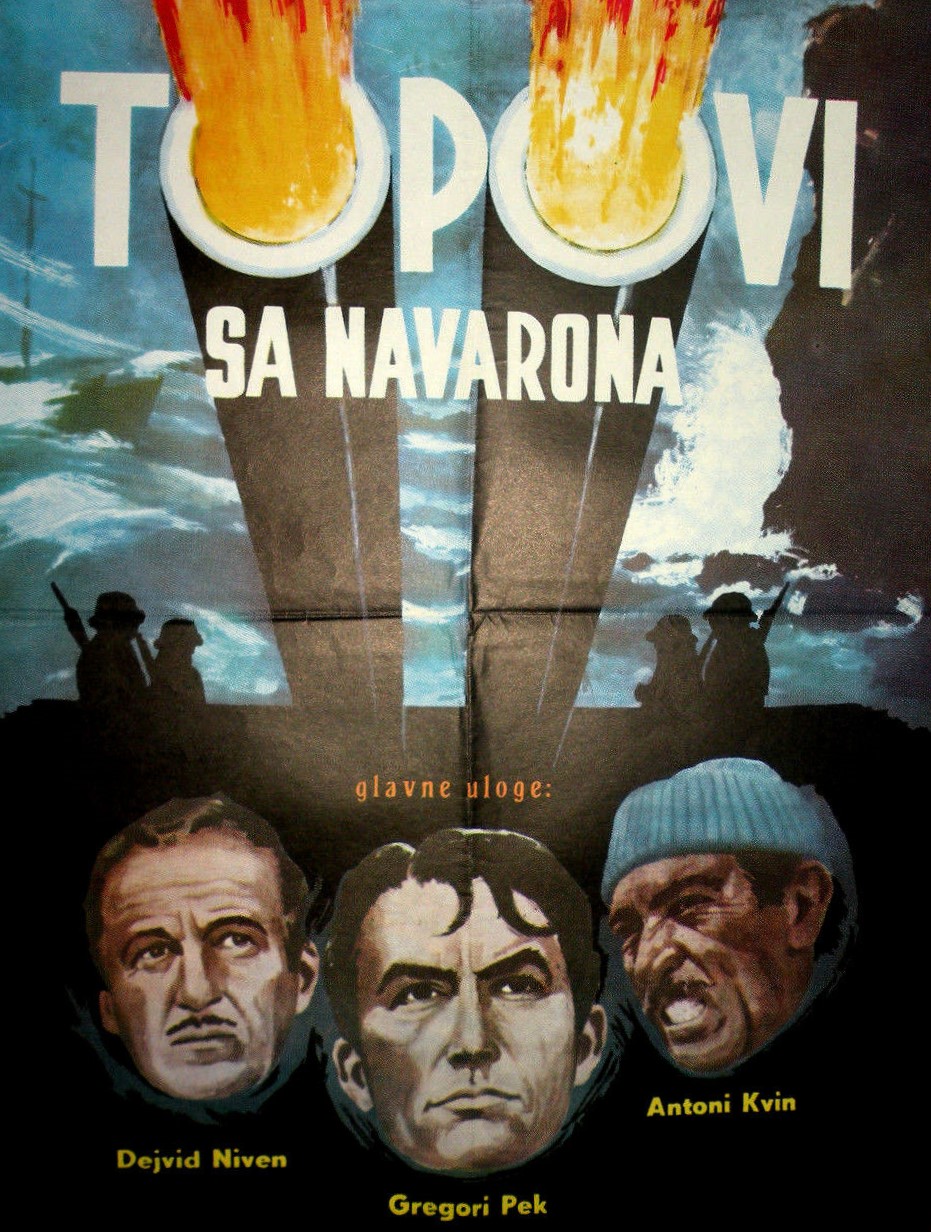

- Behind the Scenes – The Guns of Navarone (1961). The ultimate template for the men-on-a-mission war picture with an all-star cast and enough jeopardy to qualify for a movie of its own.

- Book Review – The Gladiators vs Spartacus Vol 1. Stupendous research by Henry MacAdam and Duncan Cooper explains how close Yul Brynner’s version of the Spartacus legend came to beating the Kirk Douglas movie into production.

- Behind the Scenes – The Satan Bug (1965). The problems facing director John Sturges in adapting the Alistair MacLean pandemic classic for the big screen.

- Box Office Poison – 1960s Style. Actors and actresses who had been big box office draws at the start of the decade were floundering by its end. This examines which stars while pulling down big salaries were not pulling their weight.

- Behind the Scenes – The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968). Cult classic starring Marianne Faithful and Alain Delon had a rocky road to release, especially in the U.S. where the censor was not happy.

- The Bond They Couldn’t Sell – Dr No (1962). Despite the movie’s later success and the colossal global box office of the series, American cinema owners were very reluctant to spend money renting what was perceived as just another British film.

- When Alistair MacLean Quit: Part One. Rankled by his treatment by his publishers, the bestselling author gave up his bestselling career. And not once, but twice (see When Alistair Quit: Part Two).

- Book Review – Dreams of Flight: The Great Escape (1963) in American Film and Culture. Dana Polan’s definitive book on the making of the POW classic starring Steve McQueen.

- Behind the Scenes – Genghis Khan (1965). A venture into epic European filmmaking with an all-star cast led by Omar Sharif.

- Bronson Unwanted. By the end of the 1970s Charles Bronson was one of the biggest stars in the world, but at the end of the 1960s, although highly appreciated in France, his movies could not get a box office break elsewhere.

- Pressbook – Dark of the Sun (1968). How MGM sold the action picture starring Rod Taylor and Jim Brown. Fashion anyone?

- Selling Doctor Zhivago (1965). MGM’s efforts to create huge audience awareness of the David Lean epic prior to its British launch.

- Behind the Scenes – The Night They Raided Minskys / The Night They Invented Striptease (1968). The convoluted background to the attempts by neophyte director William Friedkin to make a movie celebrating America’s vaudeville past.

- Advance Buzz. How Hollywood began to take on board the need for publicity long before the opening of a picture.

- Behind the Scenes – Topaz (1969). Detailing the problems facing Alfred Hitchcock in turning the Leon Uris bestseller into an espionage classic featuring a non-star cast.

- Book Review – The Gladiators vs Spartacus Vol 2. Abraham Polonsky’s longlost screenplay about Spartacus is brought to light.

- The Miracle of Mirisch. The Mirisch Bros were the top independent producers in the 1960s – the first of the mini-majors – and while releasing classics like The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape were also responsible for a pile of turkeys.

- Book into Film – Dr No (1962). How the filmmakers adapted the Ian Fleming original to create the James Bond template.

- Behind the Scenes – Cast a Giant Shadow (1965). Producer Melville Shavelson wrote a book about his experiences and this and other material relating the arduous task of bringing the Kirk Douglas-starrer to the screen are related here.

- Book into Film – A Cold Wind in August (1961). The novel was a lot sexier than the film, since publishing did not face the same restrictions as Hollywood, and this examines how far the movie went to retain the spirit of the book.