Until a technological invention first used in Once a Thief (1965) it was impossible to shoot “day for night” without it appearing very obvious. So when director Vincente Minnelli aimed for as much verisimilitude as possible for the Rome-set drama it meant half the shoot took place at night. “Minnelli could sleep easily during the day,” recalled star Kirk Douglas (The Arrangement, 1969), “sometimes till six o’clock in the evening, but I couldn’t so there were three unpleasant weeks of night shooting and not much sleep.”

But the movie suffered, Douglas later complained, by studio interference at the editing stage. When the movie fell foul of the Production Code, change of MGM management vetoed the more salacious aspects of the movie – the worst aspects of “La Dolce Vita” including a sequence in a nightclub where guests watched an unseen sexual act. Fifteen minutes were cut including a scene that showed Cyd Charisse’s character in a more sympathetic light. In an ironic reflection of the film’s narrative, Minnelli played no part in the editing, not due to production deadlines as in the movie, but out of choice.

The actual producer John Houseman – producer of Douglas starrers The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) and Lust for Life (1956) though later best known as an actor in Rollerball (1975) etc – backed out of any tussle with MGM head honcho Joseph Vogel. Douglas implored Vogel and editor Margaret Booth, to no avail. Consequently, in Douglas’s opinion, the film was “emasculated.” He argued MGM had turned an “adult” picture into a “family” film. Quite how this could be squared with marketing that promised a “shocking intimate view of Rome’s international film set” (see below) was not mentioned.

Following the commercial and artistic success of Spartacus (1960), Douglas was at the peak of his career, though his last three pictures had been flops. After nabbing an Oscar for Gigi (1959), Minnelli also enjoyed a career high, and although best known for musicals like Meet Me in St Louis (1944) and An American in Paris (1951) was equally adept at drama like The Bad and the Beautiful, Lust for Life (1956) and Some Came Running (1958). But he, too, was running empty, his last three serious films – Home from the Hill (1960), All the Fine Young Cannibals (1961) and big-budget roadshow The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962) coming up short at the box office.

Douglas earned $500,000 and a percentage of the profits (though none were forthcoming – it made a loss of $3 million) and top-billing. Although co-star Edward G. Robinson (Seven Thieves, 1960) appeared above the title, Douglas refused to accord female lead Cyd Charisse (Maroc 7, 1967), on one-tenth of his salary, that concession.

Douglas recalled that he build up his acting skills through wrestling. A college wrestling champ, he barnstormed across the country in a carnival, playing the cocky person reputedly from the audience who challenged the giant resident wrestler. “My job was to make the audience think he was going to murder me,” Douglas told the Pressbook/Campaign Manual. “And the way to do this was by expressions on my face. To yell out in pain would seem cowardly. But I learned a hundred and one ways of showing it through use of my eyes and the muscles in my face.”

The actor escaped serious injury when lightning, preceding one of the worst thunderstorms in a decade, struck a 200-year-old clock on the top of the church in Santa Maria Square. Four huge iron numerals were torn off and crashed to the ground, one grazing Douglas’s head.

In fact, the movie’s authenticity owed much to being filmed on the streets of Rome rather than reconstructed on the studio lot. In particular, scenes utilizing the Via Veneto, two long blocks of sidewalk cafes where the movie industry socialized, created a realistic atmosphere, especially when a hundred or so of the extra employed were actually people who would naturally populate the location. So, for example, when the script called for an opera star among the extras, casting director Guidarino Guidi used Bostonian Ann English, an opera singer studying in Rome. Among those sitting in the background at café tables were a promising young painter, a poet and a librettist.

George Hamilton (Act One, 1963), who had worked in Home from the Hill and just finished Light in the Piazza (1962) also shot in Rome, reckoned he couldn’t have been more miscast given his role called for a “funky James-Dean type.” He got the role through the influence of Betty Spiegel, wife of producer Sam, and her friend Denise Gigante, the director’s current girlfriend (later wife). Hamilton drove around in a red Ferrari costing $18,000 (ten times that at today’s prices) and, as he put it, “Italians knew how to worship” Hollywood stars.

Hamilton reckoned part of the problem of the film was that Minnelli was so “besotted with Denise that he had lost his vision.” Jumping to the defence of Cyd Charisse against a tirade from journalist Oriana Fallaci at the Venice Film Festival won Hamilton, unexpectedly, the cover of Paris-Match.

Daliah Lavi owed her career break to Douglas. As a nine-year-old in Hiffa, Israel, she struck up a friendship with the actor when he was filming The Juggler there in 1952. The actor and other stars attended her birthday party, Douglas presenting her with a ballet dress. Later a dancer and then an actress, this was her Hollywood debut. Erich von Stroheim Jr, making his movie acting debut, had his head shaved to make him appear more like his famed director father. Originally employed as an assistant director on the picture, Minnelli decided he would make a good Ravinski, the “fast-talking press agent.”

Chauvinism reared its ugly head, especially when women had to apologise for being on the receiving end. “What goes on in the minds of beautiful women when they get slapped for the cameras?” mused the editor of the Pressbook/Campaign Manual. Rossano Schiaffino’s response regarding being whacked on the behind by Douglas: “He hits hard so charmingly I didn’t mind standing up for a day of two.”

The actress proved tougher than many of her colleagues. She turned down the offer of a double for a scene in which she jumped into a lake. That might not have been such an undertaking had the sequence been shot in the hot Italian sunshine at the height of summer. But the MGM studio tank on Lot 3 was a different – and much colder – proposition. “She shrugged off her stunt with the remark that heated pools are unknown where she comes from.”

Irwin Shaw, author of the best-selling source novel, wasn’t too upset at the way the movie turned out. “An author who wants complete control of his work on the screen is in something of a cleft stick,” he observed. “He can either go into production himself, which is often neither possible nor desirable, or he can refuse to sell his work to the movies. Minor deviations in screen conception don’t send me reeling back a stricken man. I think I’m sufficiently realistic to know that even in the most enlightened films there must be some compromise if they are to be a success. What does matter very strongly to me is that the theme of the novel…should come over on the screen.”

Music trivia: Kirk Douglas was the first big Hollywood star to perform “The Twist” on screen and the song “Don’t Blame Me” was reprised from The Bad and the Beautiful, sung here sung by Leslie Uggams and in the older film by Peggy King.

French designer Pierre Balmain created the dresses, allowing a marketing campaign to be built around those stores which supplied his clothes. TWA, which flew directly to Rome, was suggested to cinema owners as an ideal tie-in. Not only did New American Library issue a new movie tie-in paperback/soft cover but cinemas were encouraged to build a campaign around a director, many of whose films would be well-known to audiences. The marketeers also had material to tie in with stores retailing music, women’s sportswear, menswear, men’s sweaters, beauty and hair styling.

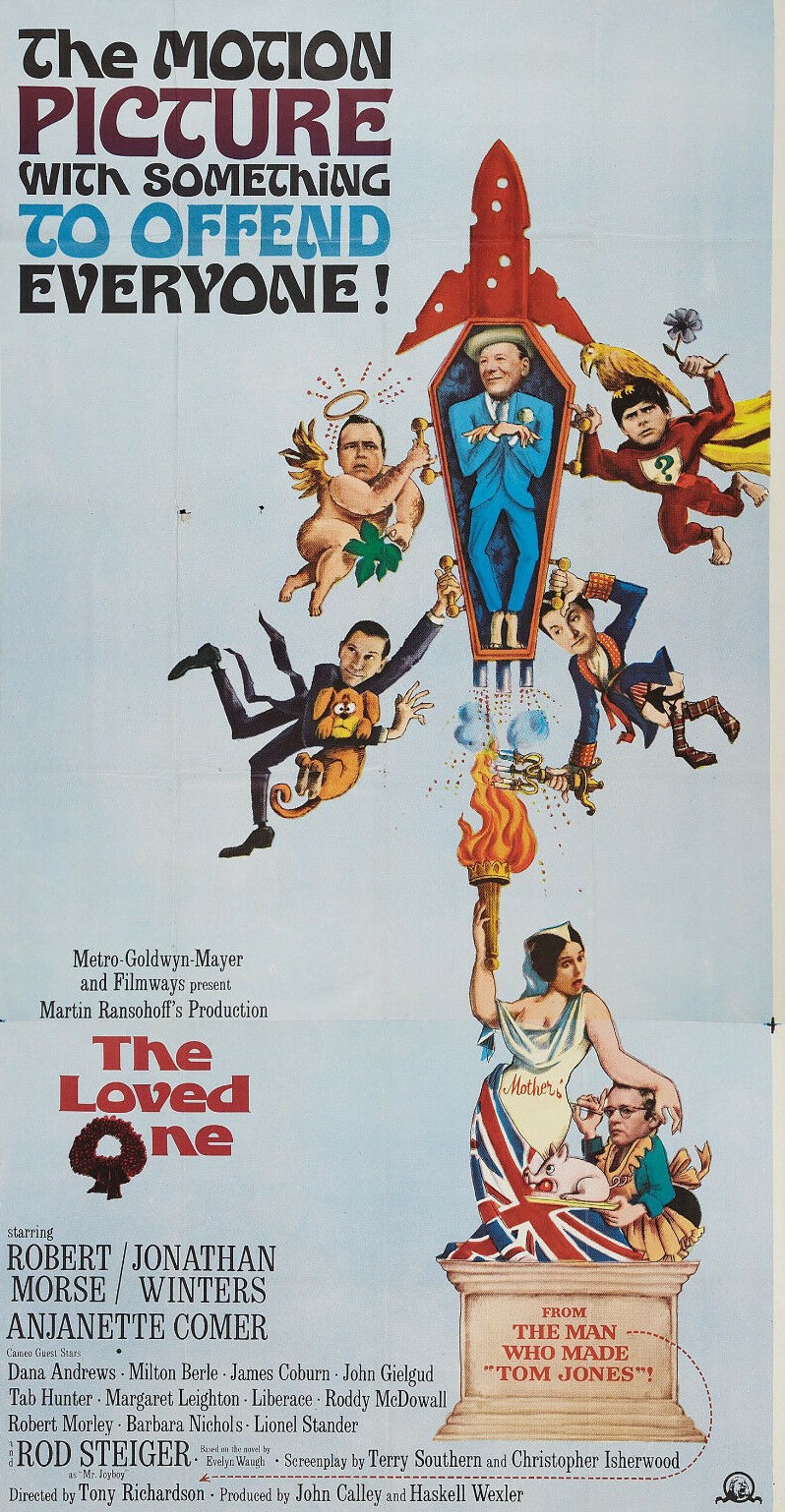

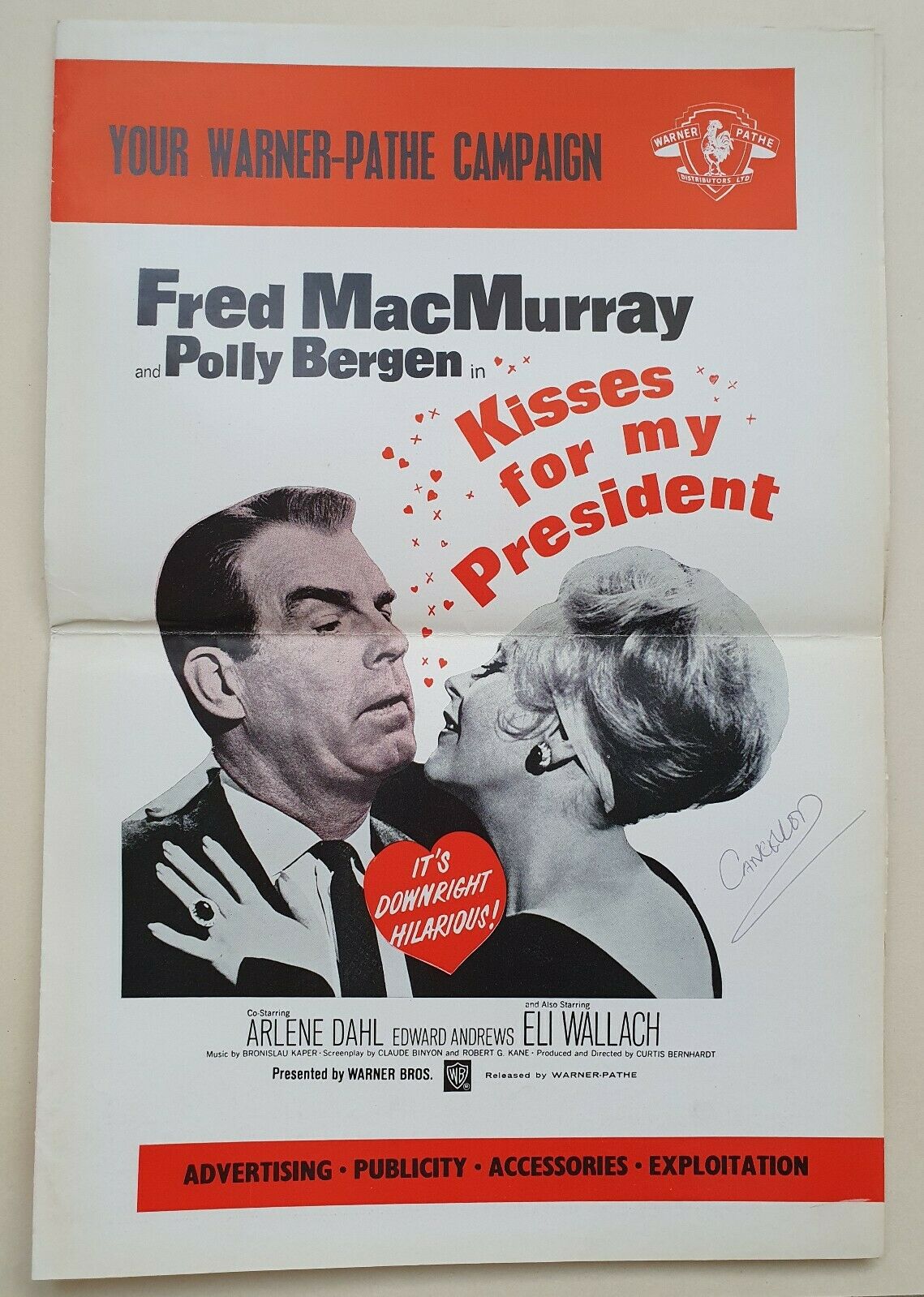

The 16-page A3 Pressbook/Campaign Manual offered a selection of advertisements and taglines. The key advert tagline ran “Another town…another kind of love…one he couldn’t resist…the other he couldn’t escape.” But there were alternatives: “Only in Rome could this story be filmed/Every town has women like Carlotta and Veronica and the kind of man they both want!/From Irwin Shaw’s great best seller.”

Or you could opt for: “Irwin Shaw’s shocking intimate view of Rome’s international film set. The world only sees the glamor. This is the drama behind it!.” Or: “Only in Rome could this story happen. Only in Rome could this story be filmed!”

SOURCES: Kirk Douglas, The Ragman’s Son (Simon and Schuster paperback, 2010) p342-344; George Hamilton, Don’t Mind If I Do (JR Book hardback 2009)pp 155-159; Pressbook/ Campaign Manual, Two Weeks in Another Town (MGM).