Pure confection. There was a sub-genre of romantic comedy pictures that spun on a simple plot device to throw together actors with terrific screen charisma. Doris Day, Rock Hudson and Cary Grant did little more than meet a potential new partner, fall out with them and then resolve their differences. The importance of actors of this calibre was the difference between a high class piece of froth and mere entertainment. This falls into the latter category, neither Ann-Margret nor Anthony Franciosca reaching the high standards of the likes of That Touch of Mink or Pillow Talk.

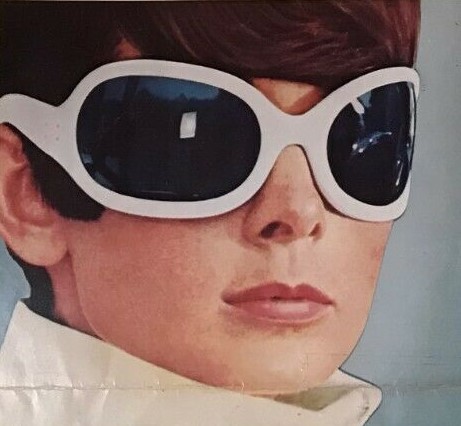

That said, this was clearly custom-made for Ann-Margret and her growing fan-base. Despite displaying unexpectedly serious acting chops in Once a Thief (1965) this plays more obviously to her strengths. She gets to sing, dance and generally throw herself around. The face, hair, smile and body combine in a sensational package.

Kelly Olsson (Ann-Margret) plays a budding writer so naïve she tries to sell her stories to Girl-Lure, a Playboy-type magazine, owned by high-class Brit Sir Hubert Charles (Robert Coote) and run by Ric Colby (Anthony Franciosca). When her work is rejected, Olsson writes an imitation sex-novel, The Swinger, purportedly based on her own life. Sir Hubert buys the idea and Ric sets up a series of accompanying photo-shoots using Kelly as the model until he discovers her book is pure fiction.

The setting is an excuse to show an avalanche of young women in bikinis. The slight story is justification enough for Ann-Margret to strut her stuff as a singer and dancer. Since her stage show depended more on energy than singing, this effectively showcases her act.

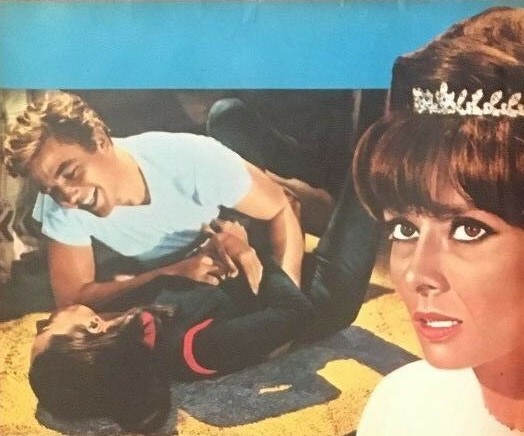

So two-dimensional are the principals, you are not going to mistake any of these characters for actual characters. The film lacks such depth you would not be surprised if the likes of Elvis Presley or Cliff Richard popped up. The comedy is very lite, an initial attempt at satire soon dropped, the few bursts of slapstick seeming to catch the stars unawares.

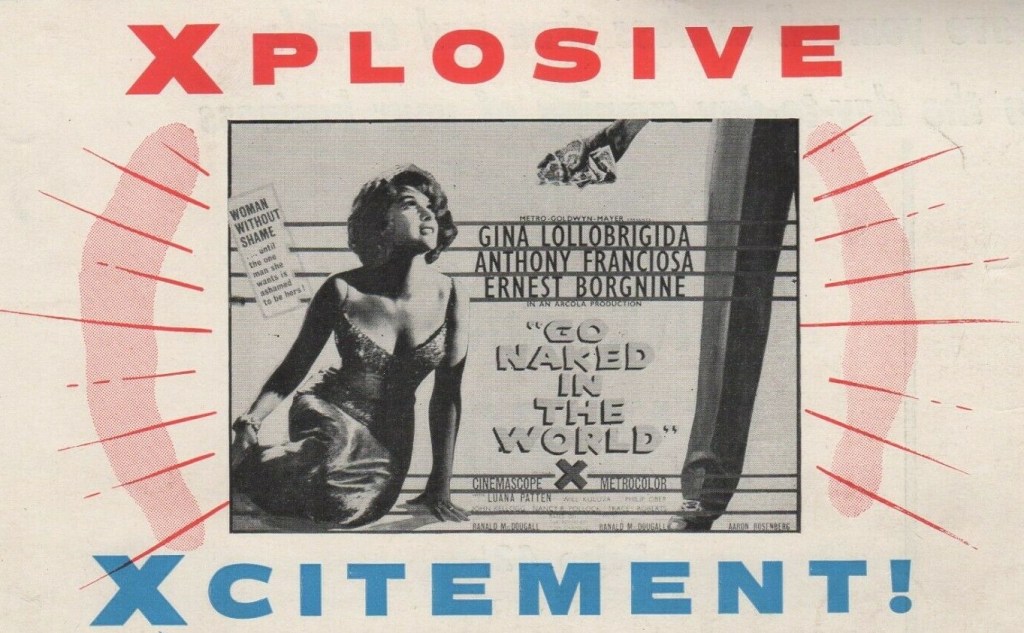

But that’s not to say it’s not enjoyable, Ann-Margret is a gloriously old-fashioned sex symbol and certainly knows how to shake her booty. The standout (for lack of a better word) scene revolves around body painting. She even gets the chance to ride a motorcycle, one of her trademarks. Anthony Franciosca (Go Naked in the World, 1961) has little to do except smile. Yvonne Romain (The Frightened City, 1961) has a thankless role as Ric’s girlfriend.

Director George Sidney teams up with Ann-Margret for the third time after Bye Bye Birdie (1963) and Viva Las Vegas (1964). This was his penultimate outing in a 20-year Hollywood career whose highlights included Anchors Aweigh (1945), The Three Musketeers (1948), Annie Get Your Gun (1950), Showboat (1951) and Pal Joey (1957). So he certainly had the musical pedigree to ensure the songs had some pizzazz but clearly less impact on the script which was reputedly scrambled together at short notice by Lawrence Roman (McQ, 1974) to fulfil a studio commitment to the star.

The film is available on Youtube.

CATCH-UP: Previous Ann-Margret films reviewed in the Blog are The Cincinnati Kid (1965) and Once a Thief (1965).