It’s Angie Dickinson vs Ann-Margret at the top of the All-Time Top 40. The two female stars take four of the top seven spots with Ann-Margret’s The Swinger replacing at the top long-time favorite The Secret Ways. These two have been duking it out over the past year, in which time the top spot has changed hands four times, with Jessica and Once Upon a Time in the West also taking a turn in the premier position. It’s also noticeable that women are top-billed in seven of the pictures in the Top Ten.

I started this Blog three years ago in June. Last year it was being read in 120 countries but that’s now gone up to 182 (out of the 193 recognized by the United Nations plus the Vatican state and the State of Palestine). Reviews have also increased and I’m now approaching 7,000 views a month, so thanks to you all.

I’ve been doing an Annual Top 40 since I started so this is the third iteration of that idea based on those reviews – out of the 900-plus posted so far – which have attracted the most attention over the three-year period. This isn’t my choice of the top films in the Blog, but yours, my loyal readers. The chart covers the films viewed the most times since the Blog began, from June 1, 2020 to July 31, 2023. (Yeah, it should have been May 31, but I’ve been remiss.)

- (7) The Swinger (1966). Ann-Margret struts her stuff as a magazine journalist trying to persuade Tony Franciosa she is as sexy as the characters she has written about.

- (-) Once Upon A Time in the West (1968). Rated the top western of all time, Sergio Leone’s operatic epic with Claudia Cardinale, Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson and the astonishing Ennio Morricone score.

- (2) Jessica (1962). Innocently gorgeous widow Angie Dickinson finds her looks turn so many male heads in a small Italian town that the female population seek revenge.

- (5) Fraulein Doktor (1969). Suzy Kendall in the best role of her career as a sexy German spy in World War One.

- (-) Stagecoach (1966). Ann-Margret, Alex Cord and Bing Crosby in decent remake of classic John Ford western.

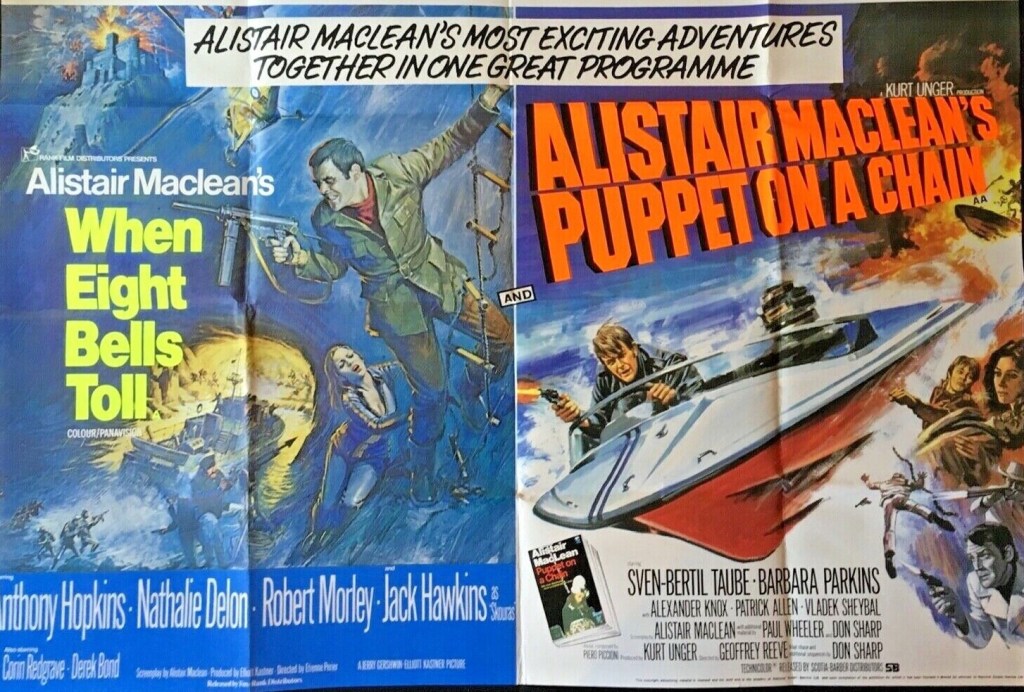

- (1) The Secret Ways (1961). Richard Widmark exudes menace in this adaptation of an early Alistair MacLean spy thriller set in Hungary during the Cold War. Senta Berger has a small role.

- (-) The Sins of Rachel Cade (1961). Angie Dickinson as a missionary who falls in love with Peter Finch in war-torn Africa.

- (-) Gerry Anderson’s Fireball XL5. Colorized version of the famed sci fi television show.

- (11) Moment to Moment (1966). Hitchcockian-style thriller with Jean Seberg caught up in murder plot in the French Riviera. Also features Honor Blackman.

- (3) Ocean’s 11 (1960). In the Rat Pack debut Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr. et al plan an audacious Las Vegas robbery.

- (17) Can Heironymous Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humpe and Find True Happiness? (1969). Off-the-wall musical awash with nudity and Fellini-esque cavorting, directed by star Anthony Newley. Has to be seen to be believed. Joan Collins pops up.

- (4) Pharoah(1966). Priests battle kings in Polish epic set in ancient Egypt. Fabulous to look at and thoughtful.

- (-) Sisters (1969). French drama bordering on the incestuous starring Nathalie Delon and Susan Strasberg.

- (-) Vendetta for the Saint (1969). Feature length version of the television show sees Roger Moore and Rosemary Dexter battling the Mafia in Sicily.

- (6) The Golden Claws of the Cat Girl (1968). Cult French movie starring Daniele Gaubert as a sexy cat burglar.

- (-) Baby Love (1969). Orphan Linda Hayden finds herself in a predatory middle-class London household.

- (-) Pendulum (1969). The under-rated George Peppard as a cop accused of murdering cheating wife Jean Seberg.

- (-) Lady in Cement (1969). Frank Sinatra reprises private eye Tony Rome as he tangles with Raquel Welch.

- (15) Subterfuge (1968). C.I.A. operative Gene Barry hunts an M.I.5 mole in London. Intrigue all round with Joan Collins supplying the romance and a scene-stealing Suzanna Leigh as a villain.

- (-) Plane (2023). Gerard Butler goes Die Hard as stranded pilot outwitting terrorists on a remote Pacific island.

- (18) Pressure Point (1962). Prison psychiatrist Sidney Poitier must help racist Nazi Bobby Darin.

- (31) Fade In (1968). Long-lost modern western with Burt Reynolds serenading low-level movie executive Barbara Loden whose company is actually filming Terence Stamp picture Blue.

- (16) A House Is Not a Home (1965). Biopic of notorious madam Polly Adler (played by Shelley Winters) who rubbed shoulders with the cream of Prohibition gangsters.

- (19) Deadlier than the Male (1967). Richard Johnson as Bulldog Drummond is led a merry dance by spear-gun-toting Elke Sommer and Sylva Koscina in outlandish thriller.

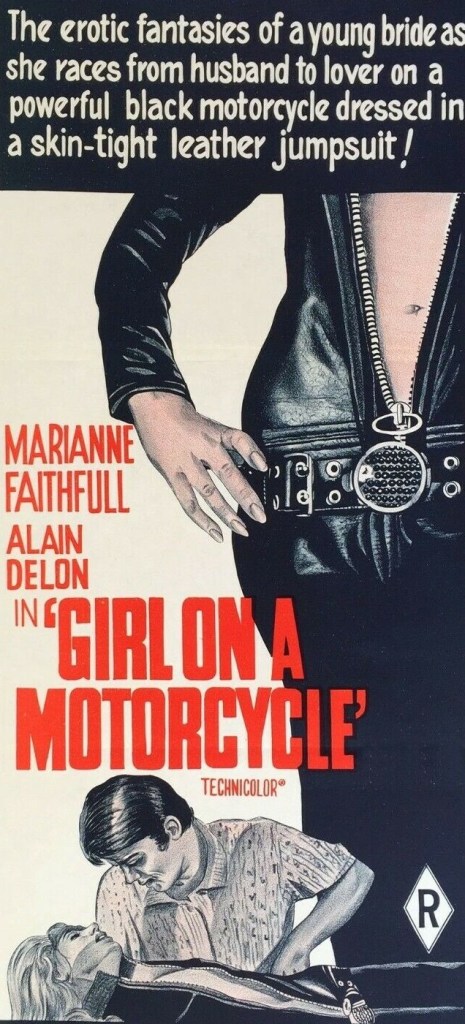

- (-) The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968). Marianne Faithful dons – and slips out of – leathers in erotic drama with Alain Delon.

- (-) Some Girls Do (1969). Daliah Lavi and Beba Loncar get tough with Bulldog Drummond in sequel to Deadlier than the Male.

- (-) Beat Girl / Wild for Kicks (1960). London teenager heads for shady Soho. Starts out in milk bars, ends up in strip clubs.

- (-) Sodom and Gomorrah (1962). Robert Aldrich biblical epic sees Stewart Granger giving way to temptation in the infamous locale.

- (-) A Dandy in Aspic (1968). Director Anthony Mann died during shooting of spy picture so star Laurence Harvey took over. Mia Farrow co-stars.

- (-) The Brotherhood (1968). Martin Ritt’s Pre-Godfather take on the Mafia starring Kirk Douglas and Alex Cord as duelling brothers.

- (23) Once a Thief (1965). Ann-Margret (again) is a revelation in crime drama with ex-con Alain Delon coerced into a robbery despite trying to go straight. Supporting cast boasts Jack Palance, Van Heflin and Jeff Corey. .

- (-) Uptight (1968). Jules Dassin remake of John Ford classic The Informer set among black revolutionaries.

- (9) A Place for Lovers (1969). Faye Dunaway andMarcello Mastroianni in doomed love affair directed by Vittorio De Sica.

- (-) The Misfits (1961). Stunning last hurrah for Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable in John Huston tale of ageing cowboys.

- (-) Father Stu (2022). Biopic of boxer-turned-priest with Mark Wahlberg and Mel Gibson.

- (-) Blonde (2022). Andrew Dominik’s controversial take on the life of Marilyn Monroe with Ana de Armas.

- (12) 4 for Texas (1963). Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin face off in a Robert Aldrich western featuring Ursula Andress and Anita Ekberg with Charles Bronson in a smaller part.

- (-) Istanbul Express (1968). Gene Barry, John Saxon and Senta Berger involved in nefarious dealings on the other famous trans-European express.

- (33) P.J./New Face in Hell (1968). Private eye George Peppard is duped by shady millionaire Raymond Burr and mistress Gayle Hunnicutt in murder mystery.

- (10) The Venetian Affair (1966). Robert Vaughn hits his acting stride as a former C.I.A. operative turned journalist investigating suicide bombings in Venice. Great supporting cast includes Elke Sommer and Boris Karloff.

Dropping out of the Top 40

The surge of new entrants and other films attracting a vast new audience has meant some previous favorites tumble out of the Annual Top 40. (Previous year’s position shown in brackets).

(8) It’s Not All Rock’n’Roll (2020). Ageing rocker Dave Doughman aims to mix a career with being a father in this fascinating documentary

(13) Age of Consent (1969). Helen Mirren stars as the nubile muse of jaded painter James Mason returning to his Australian roots.

(14) The Double Man (1967). Yul Brynner chases his doppelganger in the Swiss Alps with Britt Ekland adding a touch of glamour.

(20) Valley of Gwangi (1969). Special effects genius Ray Harryhausen the star here as James Franciscus and Gila Golen encounter prehistoric monsters in a forbidden valley.

(21) The Naked Runner (1967). With his son held hostage, Frank Sinatra is forced to carry out an assassination in east Germany.

(22) Orgy of the Dead (1965). Bearing the Ed Wood imprint, mad monster mash-up with the naked dead.

(24) The Sicilian Clan (1969). Stunning caper with thief Alain Delon and Mafia chief Jean Gabin teaming up for audacious jewel heist with cop Lino Ventura on their trail. French thriller directed by Henri Verneuil. Great score by Ennio Morricone.

(25) Dark of the Sun / The Mercenaries (1968). More diamonds at stake as Rod Taylor leads a gang of mercenaries into war-torn Congo. Jim Brown, Yvette Mimieux and Kenneth More co-star. Based on the Wilbur Smith bestseller

(26) Stiletto (1969). Mafia hitman Alex Cord pursued by tough cop Patrick O’Neal. Britt Ekland as the treacherous girlfriend heads a supporting cast including Roy Scheider, Barbara McNair and Joseph Wiseman.

(27) Maroc 7 (1967). Yet more jewel skullduggery with Gene Barry infiltrating a gang of thieves in Morocco who use the cover of a fashion shoot. Top female cast comprises Elsa Martinelli, Cyd Charisse, Tracy Reed and Alexandra Stewart.

(28) The Rock (1996). Former inmate Sean Connery breaks into Alcatraz with Nicolas Cage to prevent mad general Ed Harris blowing up San Francisco. Michael Bay over-the-top thriller with blistering pace.

(29) The Swimmer (1968). Burt Lancaster’s life falls apart as he swims pool-by-pool across the county. Superlative performance.

(30) Hour of the Gun (1967). James Garner as a ruthless Wyatt Earp and Jason Robards as Doc Holliday in John Sturges’ realistic re-telling of events after the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

(32) Dr Syn Alias the Scarecrow (1963). The British movie version of Disney American television mini-series sees Patrick McGoohan as a Robin Hood-type character assisting local smugglers.

(34) Sol Madrid/The Heroin Gang (1968). In his second top-billed role David MacCallum drags hooker Stella Stevens to Mexico to capture drugs kingpin Telly Savalas.

(35) A Twist of Sand (1968). Diamonds again. Smugglers Richard Johnson and Jeremy Kemp hunt long-lost jewels in Africa. Honor Blackman is along for the voyage.

(36) Genghis Khan (1965). Omar Sharif plays the legendary warlord who unites warring Mongol tribes. Stellar cast includes Stephen Boyd, James Mason, Francoise Dorleac, Eli Wallach, Telly Savalas and Robert Morley.

(37) Interlude (1968).Bittersweet romance between famed conductor Oskar Wener and young reporter Barbara Ferris.

(38) Woman of Straw (1964). Sean Connery tangles with Gina Lollobrigida in tangled tale of the killing of wealthy uncle Ralph Richardson.

(39) Bedtime Story (1964). Marlon Brando and David Niven are rival seducers on the Riviera targeting wealthy women.