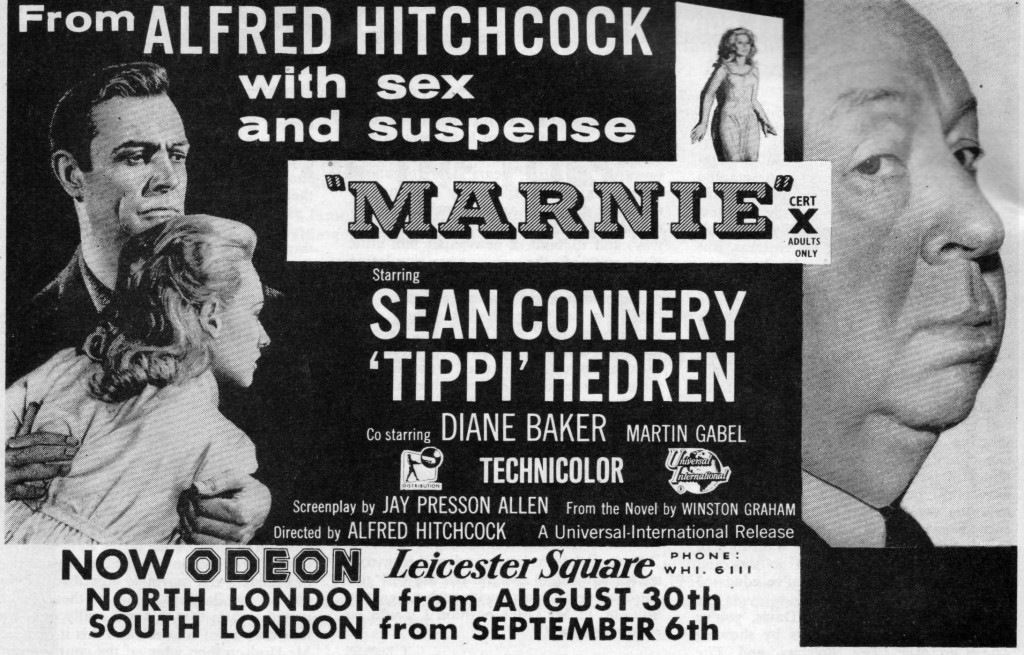

Arguably Alfred Hitchcock’s most difficult film and with some attitudes that will not sit well with today’s audiences nonetheless this is an assured work and the completion of an unofficial trilogy that tries to explain the unexplainable. The director had not been making what might be termed traditional Hitchcock pictures for well over half a decade if you take North by Northwest (1959) as the anomaly in a sequence that began with the obsessive Vertigo (1958). You could argue that Hitchcock had turned a bit “north by northwest” himself, the “hero” of Psycho (1960) a mother-obsessed serial killer, the “bad guys” in The Birds (1963) the titular rapacious creatures who besiege the leading characters and set the world on an apocalyptical course.

Attempts are made in both Psycho and The Birds to explain the actions of the predators, but such explanations are external, remote, and with Marnie Hitchcock takes the bold step of attempting to explain what makes such a devious, compulsive, frigid liar tick. Hitchcock called the movie a “sex mystery” but it was unclear whether he was just once again trying to tantalize his audience or whether he believed it was film about the mystery of sex, what causes attraction between two people and what sets others up to steadfastly reject the concept. To embellish his thesis he chose one of the world’s most beautiful actresses (Tippi Hedren) and the actor (Sean Connery) who could easily lay claim to being the world’s sexiest man (as he was later anointed in various polls).

It seemed almost an indecent proposal to deny the bed-hopper-par-excellence – as viewed from the James Bond perspective. And it certainly took all the charm Connery could muster to prevent audiences baulking at the almost perverse scientific aspects of his character, an amateur zoologist who welcomed a known criminal into his world for the chance to examine her at close quarters. The audience is constantly kept at one remove. In the first section we watch enthralled as Hedren carries out her bold thefts, as if she is capable of wrapping the entire male population around her little finger by the simple device of adjusting her skirt.

But in the middle section, it is Connery who is in control and the trapped Hedren who is twisting and turning searching for an escape route. In the final section, when it is clear that it is the lover, not the scientist, in Connery that tries to find a way round the problem, the tension is at its height because we have no idea whether she will run true to form and manage to steal and lie her way out or whether Connery’s patience will snap and he will throw her to the wolves who are certainly by this point circling.

The central device on which Hitchcock hooked an audience was the moviegoer demand for a happy ending. He duped cinemagoers in Psycho, slaughtering the heroine halfway through. In The Birds Rod Taylor and Tippi Hedren underwent a harrowing physical assault and while clearly romantically involved by the end Hedren was a wreck. Here, the assaults are mental. There is none of the romantic banter that defines the greatest of his traditional works. Hedren and Connery are together because he has forced the issue and loving though his blackmail is it is still an unequal relationship and one from which she will seek to escape at every opportunity. Hedren’s compulsive character is a mystery that appears insoluble as she resists every attempt to break down the wall she has erected to protect herself from her past.

The story is straightforward with few of the twists of other pictures. We meet Hedren as she escapes with nearly $10,000 stolen from her employers. We learn quickly that she is a master of disguise, has several social security cards up her sleeve, can turn from brunette to blonde, and is so practiced in her deception that she can convince an employer to take her on without references. As that particular duped employer is spelling out his predicament to the police, an amused Sean Connery, a customer of her employer, appears. Hedren runs off to a bolthole, an upmarket hotel, close to the stables where she keeps a horse, Forio.

Shifting back to Hedren we find her visiting her mother in a tawdry street near the docks. The artifice of confidence is shredded away. She is jealous of the attention her mother gives a little girl whom she looks after. She wants love that her mother is unable to give. When she lays her head on her mother’s lap waiting for the soothing stroke of a hand all she receives is rebuke for leaning too heavily on her mother’s sore leg. The mother in North by Northwest was played for comedy, in Psycho an occasion for murder, and here a means of control. Here, too, we witness the color red sparking an inexplicable and frightening experience.

When Hedren applies for a new job it is at Connery’s firm, where he is the coming man. He watches amused as she is interviewed, intervenes to ensure she is hired. They have in common that they are widowed. Hedren is already planning her next big score, discovering that the combination to the safe is kept in a drawer to which her employer’s secretary has the key.

But he is ready for her and it seems almost perverse that he does not let her know he is aware of her true identity. Instead, under the guise of asking her to work overtime, he gives her an academic paper to type. The subject is predators, “the criminals of the animal world” in which females feature. His gentle pressure is almost sadistic and she is saved by a sudden storm which triggers another bad subconscious reaction.

Her theft of money from the office is a classic Hitchcock scene. It begins in complete silence. The screen is divided in two, the office and the corridor. Seeing a cleaner appear, Hedren removes her shoes to make her getaway. Almost as she reaches the safety of the stairs, a shoe falls out of her pocket and clatters on the floor. The cleaner does not look up. She is very hard of hearing.

But Connery is again prepared and when she disappears tracks her to her bolthole, confronts her, questioning her again and again until he thinks he is close to the truth. He can’t turn her in because he has fallen in love. Her choice is stark – him or the police. Soon they are married. But the honeymoon, despite his patience, is a disaster, she cannot “bear to be handled” and they return home further apart than ever.

Meanwhile, figures from her past begin to appear. Lil (Diane Baker) who lusts after Connery brings peril to their door. Connery persists with trying to get Hedren to open up.

Eventually, there is a break in her compulsive syndrome, brought on by love, and we head back to her mother’s to get to the root of the problem. Even when the problem is solved her mother remains distant, still won’t stroke her hair. If there is a happy ending it is like that of The Birds, an immediate problem solved but who knows when or if the crows will return, and there is a similar resolution here, Hedren learns the source of her nightmares but it would be a very blind person who did not see terrible ramifications for the future.

There are certainly a few jarring moments, Hitchcock’s insistence on back projection for a start, but then you didn’t really think in North by Northwest that the director was allowed to film in front of the United Nations, did you? Rather than a technical flaw, the back projection seems to fit another purpose, a device to make the audience stop and examine what is going on, for much of it occurs when Hedren is in her fantasy world. And you would have to take exception to Connery’s actions in the bedroom on honeymoon, no matter how gentle his caresses at other times. And certainly, the psychological assumptions ring hollow given our current knowledge of such conditions, but despite that make for tense viewing.

But the meat of the movie is self-deception. Hedren is convinced she can get away with a series of thefts. Connery is convinced her can cure her. His constant interrogation is what passes for lovers’ banter. In aligning himself as her moral guardian and perhaps her savior, “dying to play doctor,” Connery has entered a nightmare of his own making. Only an arrogant man would believe all women would fall at his feet and Hitchcock clearly makes a connection with Connery’s ongoing incarnation as James Bond where that is exactly the case. Connery is every bit as flawed, as obsessive, as Scottie in Vertigo, determined to shape a woman into perfect form, and, yes, expecting to eradicate the imperfect past.

Connery emanated such ease, such amazing grace, on the screen that it backfired. Critics often didn’t believe he was putting much into his acting when in reality he was acting his socks off. This is a tremendously difficult part, walking the tightrope between looking a deluded fool and retaining audience empathy and coming across badly when he pushes a vulnerable woman too hard. This is a very rounded character, a gentle adoring lover in the main, but not one to be crossed. His interrogations are intense and yet still you can see that it will kill him if he is double-crossed. The casual amusement with which he greeted her appearance at his office is replaced by fear at her sudden departure.

Hedren, too, whose acting ability was often called into question, carries on where she left off in The Birds. By the end of that picture her nerves had been shredded. Here, her emotions, which she cannot as easily control as the rest of her life, too often fly off into a high pitch. Half the time she is the cool collected customer of The Birds, the rest of the time she is demented. Except in The Birds she was self-confident around men. Any self-assurance she has now is skin deep. There was always a fragility about Hedren, hidden behind the glossy exterior and fashionable outfits, and here it is exposed. The touching scenes with her mother, the mouth tightened in jealousy over the little girl, are perfectly played. A little girl lost in wolf’s clothing. And trapped, she is almost snarling at her captor, the submissive dialogue concealing the mind hard at work looking for an exit.

The interrogative scenes between Connery and Hedren are extremely difficult to pull off. It would have been easier if Connery was not in love with her, and to some extent pulled his punches. It would be easier for her if he was an out-and-out predator who could be paid in kind to shut up and go away. Instead, they both have to walk a verbal tightrope and only actors of some excellence can pull off that trick without losing the audience.

Many of the films from the 1960s are to be found free of charge on TCM and Sony Movies and the British Talking Pictures as well as mainstream television channels. Films tend to be licensed to any of the above for a specific period of time so you might find access has disappeared. There is a particularly awful pan-and-scan version of this film on YouTube. But if this film is not available through these routes, then here is the link to the DVD and/or streaming service.