Director Blake Edwards shouldn’t have been anywhere near Wild Rovers in November 1970 when filming of the western kicked off in Arizona. He should have been making a musical – his second successive one following Darling Lili (1970).

Versatility had become something of a watchword for Edwards who had segued apparently effortlessly from the gentle romance of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) to thriller Experiment in Terror/Grip of Fear (1962) to alcoholic drama Days of Wine and Roses (1962) to wild comedy The Pink Panther (1963) to slapstick The Great Race (1965) – in 70mm roadshow no less – to the satirical What Did You Do in the War, Daddy (1966). So Hollywood wasn’t enormously surprised when he decided it was time he tackled a musical, Darling Lili, especially when it starred “sure thing” Julie Andrews.

And before the figures for Darling Lili came in, and everyone thought they were onto a winner, small surprise that he was in the front line to direct She Loves Me, the movie adaptation of a 1963 Broadway musical that was the second musical reincarnation – the first being The Good Old Summertime (1949) with Judy Garland – of romantic comedy The Shop around the Corner (1940) starring James Stewart.

But in 1969 – before Darling Lili slumped at the box office – a takeover of MGM by Kirk Kerkorian was imminent and in anticipation of some drastic action studio executives canned its three biggest projects, Fred Zinnemann’s Man’s Fate, the $10m She Loves Me – also to star Julie Andrews (now Edwards’ wife) – and the $12m-$15m Tai Pan. Edwards sued for $4.6 million.

Edwards had other fish to fry – his company Cinema Video Communications had purchased the latest Harold Robbins’ novel The Betsy plus The Peacemaker, the first novel by war historian Cornelius Ryan (The Longest Day). Edwards had plans to film Svengali with Jack Lemmon and Julie Andrews and Kingsley Amis’s novel The Green Man with Richard Burton.

Despite having informed MGM that he would not accept any substitute for She Loves Me, he capitulated when the studio agreed to back his pet project, a buddy western with a serious theme, Wild Rovers. Paul Newman was initially sounded out with the younger character looking a good fit for Michael Witney, expected to be the breakout star of Darling Lili.

William Holden was picky about his projects. He complained that most scripts he received were “aimed at exploitation or titillation.” Though he had not had a hit since the start of the previous decade with The World of Suzie Wong (1960), his global investments had paid off and he was happier spending seven months of the year on his 1,260-acre ranch in Kenya. He was impressed enough with the Blake Edwards script for Wild Rovers and, possibly optimistic about its commercial prospects, to defer part of his salary against a percentage of the gross (he had made a fortune from his percentage on Bridge on the River Kwai). Apart from Wild Rovers, the only movie which had caught his attention was The Revengers co-starring Mary Ure (after it was delayed due to his illness, she pulled out).

Even so, MGM held Edwards on a tight rein financially. While trying to extricate itself from a sticky corner, it had no wish to find itself in the kind of lack of budgetary restraint that had afflicted Darling Lili. And to some extent, Edwards had to prove he was more fiscally responsible. The budget for the below-the-line cast was restricted to $1.5 million. There was considerable physical commitment to the project from the two stars, training for six weeks so the scene taming the wild horse could be completed without stunt men.

MGM had high hopes for the western, backing it with a substantial promotion campaign. In the trades there were three-page ads and a separate advert paying homage to the studio’s “writer cats.” The studio had weathered the Kerkorian storm and the massive write-offs at the end of the previous decade. The mood was buoyant. The first quarter of 1971, bolstered by an unexpectedly good showing by Ryan’s Daughter (1970). While not hitting the highs of Doctor Zhivago (1965) it had done much better than the industry predicted, especially after being savaged by critics. It looked as if MGM had turned a corner. In the first three months of 1971 the studio made $2.5 million profit and was confident that summer offerings Shaft, The Last Run and Wild Rovers would maintain the good run.

After the box office fallouts of recent years, it looked as though the entire industry was on the verge of bouncing back. Released by other studios around the same time as Wild Rovers were the likes of Klute, The Anderson Tapes, Summer of ’42, Willard, and Carnal Knowledge

The reviews weren’t promising. Variety tabbed it “uneven”, only one of the top five New York critics gave it a favorable review. An opportunity to gain some critical headway was spurned when the studio pulled the movie from the annual Atlanta Film Festival in favor of an appearance by the two stars on the Dick Cavett Show.

The version released ran 110 minutes. There was no critical outcry at the film being savagely edited by the studio – nobody cared sufficiently about the picture to be up in arms about it.

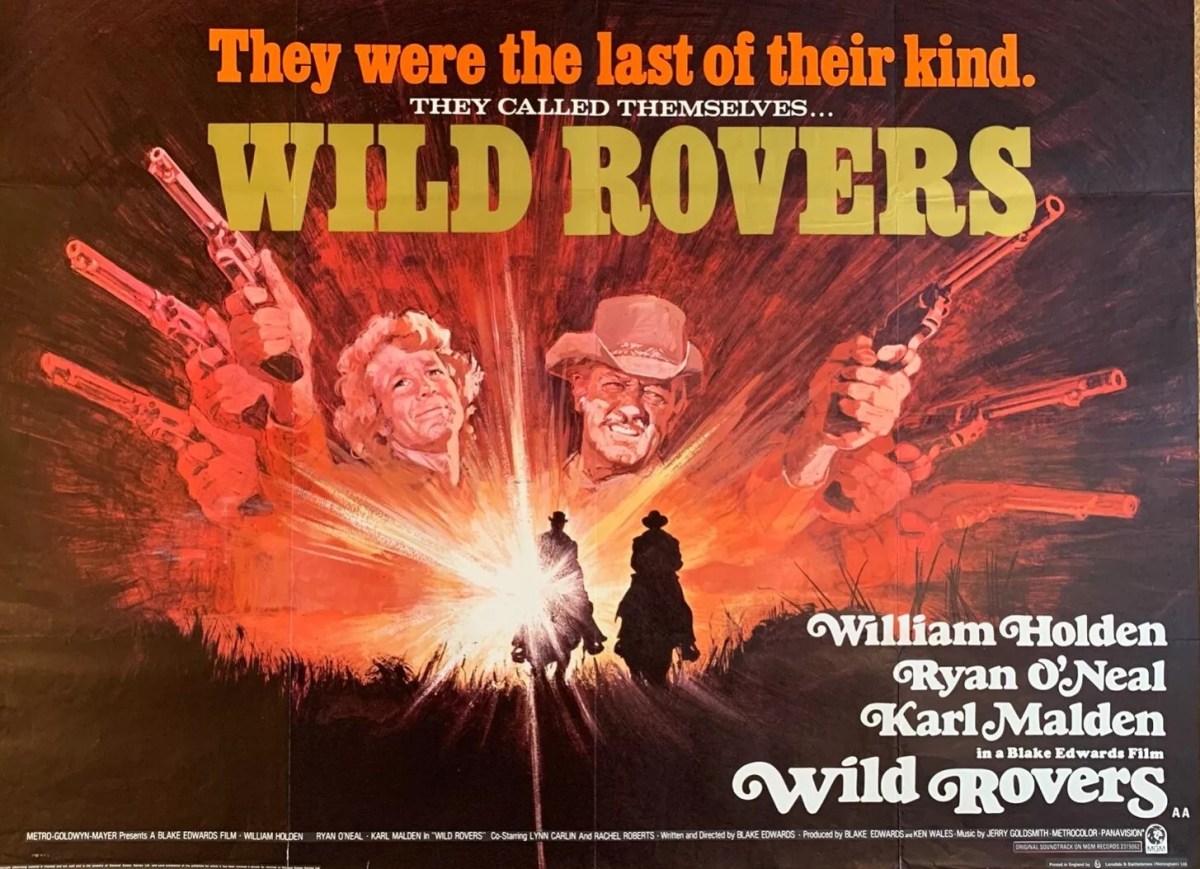

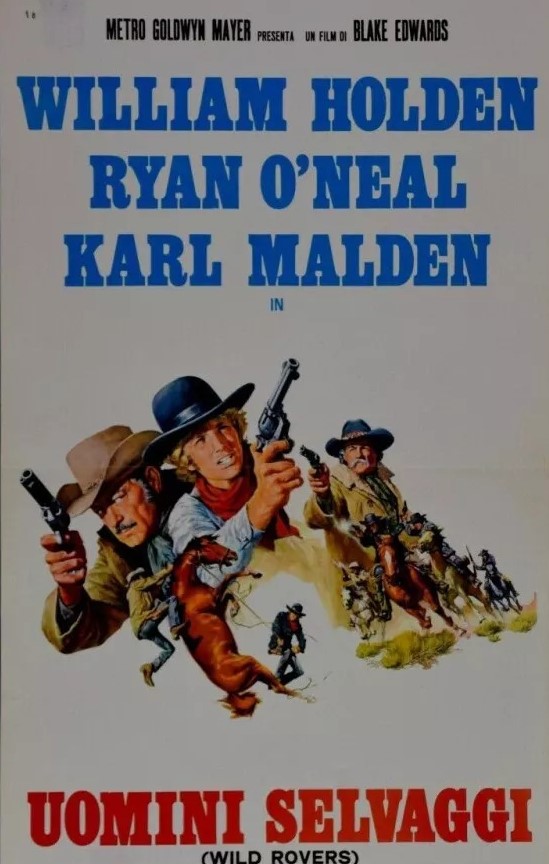

Worse, the marketing campaign was widely derided. The image of William Holden and Ryan O’Neal astride the same horse, the youngster grinning, leaning into the older man’s back, gave off, unintentionally, homo-erotic undertones. Audience dismissal of the advert only became clear to MGM at the end of the movie’s first six days at the first run Grauman’s Chinese in Los Angeles which registered less than $20,000 at the box office. Shocked at the low result, MGM “scrapped its entire pre-release and opening campaign” shifting the emphasis from the “man-to-man image” to “guns, horses and adventure” suggesting an old-fashioned shoot-em-‘up.

The new advertisement was accompanied by anonymous quotes, comparing Holden and O’Neal to Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy – though as Variety acidly noted, without identifying which was which – and describing the shootout as “so electrifying your impulse is…to run for cover.” Phantom quotes had been used before by Avco Embassy for De Sica’s war drama Sunflower (1970) starring Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni. But while Hollywood was fond of editing reviews to find an often-misleading quote, studios generally drew the line at making them up.

The New York release in a trio of first run houses coincided with the showcase outing of Love Story (1970). That movie had played for months in first run and this was the first time it was generally available. Love Story, the hit of the decade so far, would open in 80 suburban cinemas on the same day in June, 1971, as Wild Rovers. In the era before “Barbieheimer”, there was still an expectation of cross-over, that the fans of a new star coming good like Ryan O’Neal would automatically seek out his latest picture. And it may have been that the advertising campaign was specifically designed to ensure his fans did not go to the western expecting another romantic drama.

They weren’t tempted at all. Love Story cleaned up – a gross of $1.25 million from 80 outlets and another $750,000 the following week. Compared to that, Wild Rovers scarcely got out of the gate – a “less than roaring” $20,600 from the three. At the 1,096-seat Astor it was on a par with the fourth week of Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) which had just completed its run there.

There was a little solace elsewhere. Its $15,000 in Baltimore was deemed “tall” and $12,500 in Boston “slick” but more reflective of the general interest was a “dim” $65,000 from eight theaters in Detroit, a “mild” $7,500 in Denver and “moderate” $8,500 in Minneapolis. By the end of the year it had amassed $1.8 million in rentals, languishing in 59th place.

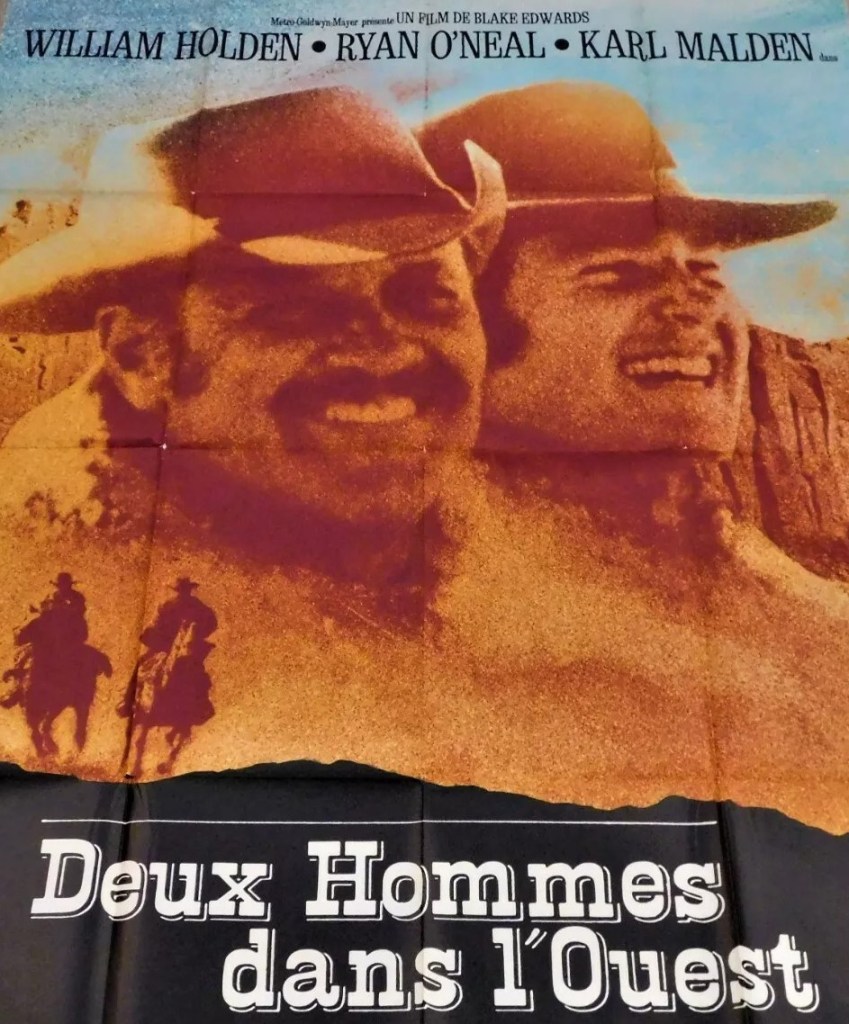

MGM took a different tack in Europe. It wasn’t unusual for movies released in 35mm in America to be shown in 70mm roadshow in Europe – The Dirty Dozen (1967), Where Eagles Dare (1968) and The Wild Bunch (1969) enjoyed up to a year in roadshow before fanning out into general release, getting two substantial bites of the commercial apple. The latter two had done better abroad than at home, in large part due to the roadshow release which turned a movie into an event rather than a routine outing. So MGM sent Wild Rovers out in roadshow. At 110 minutes, even puffed out with a 15-minute interval, it was a mighty slim offering for roadshow.

In London, half the critics came out against it, but only a quarter were favorable, the others having “no opinion.” The consensus was that it would “not survive the rough critical handling.” It opened on October 21, 1971, at the ABC2 in London’s West End. And lasted two weeks, whipped off the screen after generating an opening week of $6,200 and a sophomore of $4,100, replaced by The Last Run starring George C. Scott, another flop. MGM persevered with the roadshow. It played for five weeks at the Coliseum in my home town of Glasgow.

In the U.S. it shifted quickly to television, part of the CBS program, finishing a lowly 85th for the year in the tabulations of the movies attracting the biggest television audiences.

SOURCES: “Metro’s Loves Me As A Substitute for Former Say It With Music,” Variety, August 6, 1969, p3; Army Archerd, “Hollywood Sound Track,” Variety, October 20, 1970, p6; Army Archerd, “Hollywood Cross Cuts,” Variety, August 5, 1970, p23; “Holden Pushes for Conservation,” Variety, August 12, 1970, p25; Army Archerd, “Hollywood Sound Track,” Variety, November 4, 1970, p20; “Hollywood Production Pulse,” Variety, November 18, 1970, p54; Advert, Box Office, March 28, 1971, p3-5; “Profitable Quarter for MGM,” Kine Weekly, April 24, 1971, p3; Advert, Variety, May 17, 1971, p23-25; Advert, Variety, May 19, 1971, p12; Review, Variety, June 23, 1971, p20; “Col Delivers Atlanta Festival,” Variety, June 23, 1971, p6; “New York Critics,” Variety, June 30, 1971, p7; “Metro Scraps Rovers Campaign,” Variety, June 30, 1971, p27; “London Critics,” Variety, November 17, 1971, p62; “Big Rental Films of 1971,” Variety, January 5, 1972, p9. Box office figures from Variety June 30-August 18, 1971, and November 10-17, 1971.