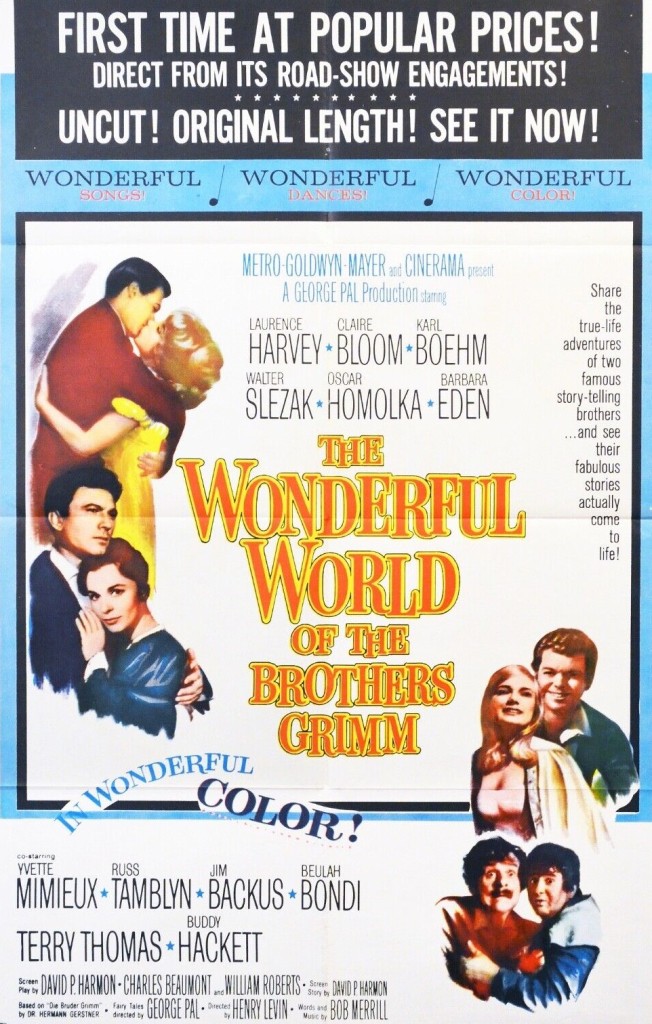

With Hollywood already snagging the best characters of the Grimm inventory – Snow White, Cinderella, The Sleeping Beauty and Tom Thumb – and others like Rumpelstiltskin not deemed cute enough, George Pal (The Time Machine, 1960) had a battle on his hands to come up with a decent enough second string. Spurning for no obvious reason contenders like Hansel and Gretel and The Frog Prince, he plumped for a strange hybrid.

He incorporated three fairy stories – The Dancing Princess, The Elves and the Shoemaker and The Singing Bone – in a drama about the authors. Both sides of this tale had a common background, 19th century Germany with its rich vein of fairy castles and cobbled streets where kings ruled. The Grimms are posited as wannabe writers but with warring personalities.

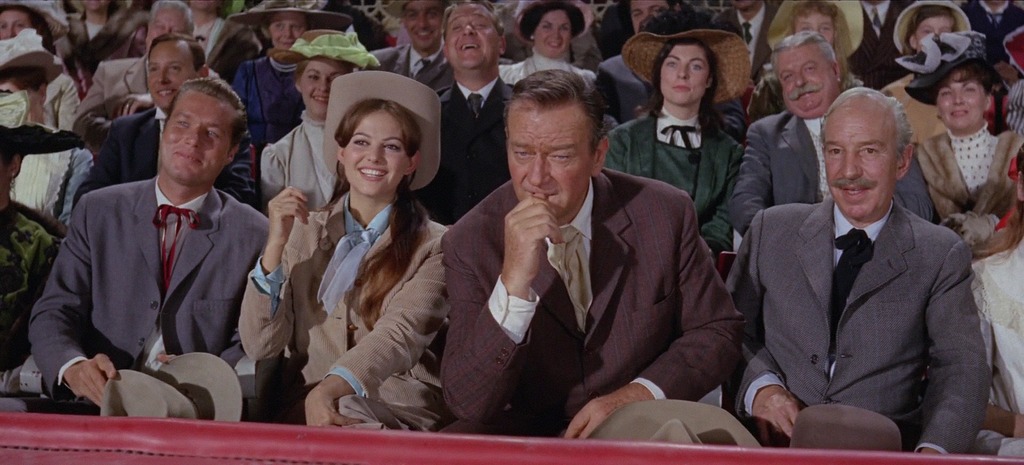

Unmarried Jacob (Karl Boehm) wants to stick to the knitting and complete the work, a biography of the Duke (Oscar Homolka), they are being paid for while married Wilhelm (Laurence Harvey) prefers to use that time instead to write down the stories he has collected from a variety of sources.

The stories Pal chooses to bring to life pop into the narrative by the simple devices of telling kids a bedtime story or overhearing the tale. Jacob is actually more interested in academic writing; books on law and grammar are what capture his imagination. The narrative switches between the brothers falling out, enduring poverty and Jacob falling in love with Greta (Barbara Eden) but lacking the romantic touch mostly making heavy weather of it.

The first tale in the triptych – The Dancing Princess – is simple enough. A King (Jim Backus) promises the hand of his daughter (Yvette Mimieux) in marriage to whoever can find out what she does at night which a humble woodsman (Russ Tamblyn) manages with the help of a cloak that makes him disappear. In the second story elves come to life to save the skin of a shoemaker more interested in helping orphans than his rich clients.

The third, demanding the biggest special effects, less successfully translates to the screen since it involves the creation of a dragon to be slaughtered. However, it is saved by humor, since the knight (Terry-Thomas) is too cowardly to do the job and relies on servant Hans (Buddy Hackett) for the actual slaying, and by the most gruesome of endings.

Plus, since it is in Cinerama, something speeding is required seen from the audience point-of-view or a hero who could fall into a canyon. And in the best fairy tale tradition the heroes are unsung and under pressure.

Laurence Harvey (A Dandy in Aspic, 1968), Karl Boehm (The Venetian Affair, 1966) , Claire Bloom (Two Into Three Won’t Go, 1969) and Barbara Eden (I Dream of Jeannie television series, 1965-1970) are just about buoyant enough to keep the main story ticking along and carve out a piece of Disney territory without so much as a decent song to help proceedings. Three unexpected twists – four if you count a miraculous recovery from serious illness – nudge this in unexpected directions.

The first is the solidity of brotherly love, with one having to choose wife over his close bond with his sibling – the kind of emotional hit that would be more common in an adult picture, though kids obviously couldn’t care less. The second is the appearance of virtually all the famous Grimm characters in what amounts to a cameo. Last is a proper fairy tale ending where it’s the kids who elevate the brothers to literary success.

Laurence Harvey hides his snide side and does his best Dirk Bogarde impression as the errant brother whose imagination brings his family to near-ruin. Despite being offered love on a plate, Karl Boehm remains steadfastly dour, while Claire Bloom as Wilhelm’s wife has little to do. Scene stealing honors go to Oscar Homolka (The Happening, 1967) while Terry-Thomas (How to Murder Your Wife, 1965) just about shades it in the comedic duel with Buddy Hackett (The Love Bug, 1968).

George Pal concentrated on the fantasy elements with Henry Levin (Genghis Khan, 1965) directing the drama so it’s a mixture of very grounded and very flighty. It’s not really long enough for a true Cinerama roadshow movie but with an overture and intermission it stretches enough.

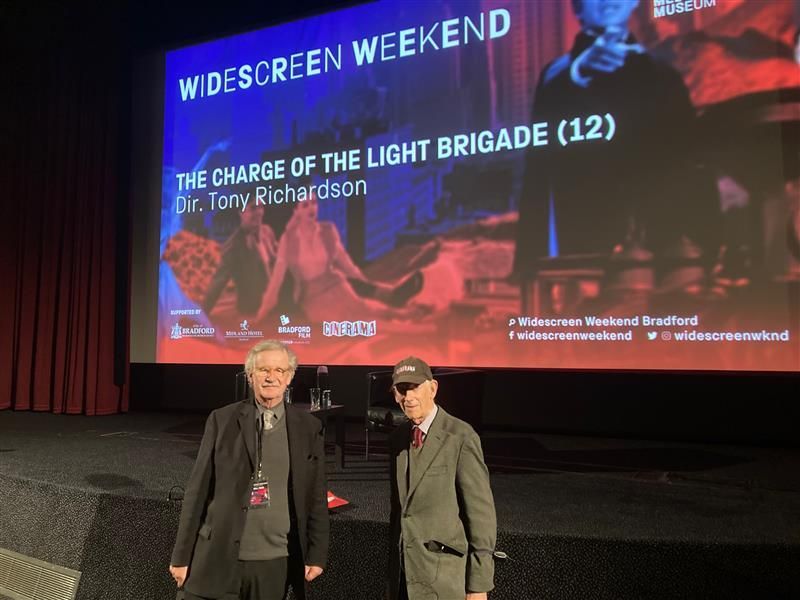

It was filmed with the traditional three Cinerama lenses and would have been projected with three projectors but at the Bradford Widescreen Weekend I saw a new restoration that does away with the vertical lines. For contemporary audiences who only view fairy stories through the microcosm of animation and for whom live-action means Ray Harryhausen, the special effects here will come as something of a disappointment. But on the other hand it is still George Pal, so enjoy.

William Roberts (The Magnificent Seven, 1960), Charles Beaumont (Mister Moses, 1965) and David P. Harmon (Dark Purpose, 1964) cobbled up the screenplay.

As I said I saw this in the magnificence of the big screen and in widescreen Cinerama to boot so I am bound to be a shade benevolent but this still holds up, the drama dramatic enough, as a biopic interesting, and kids who might be taken with the fairy stories are way too young to complain about the effects.