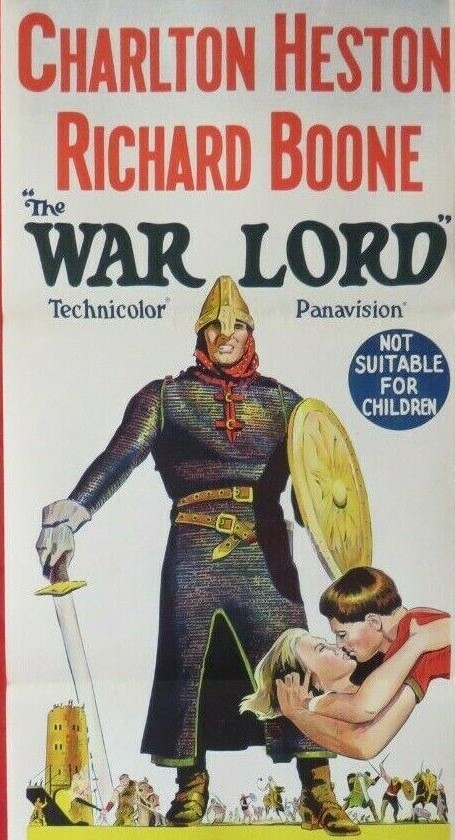

King Arthur (plus Excalibur) meets Robin Hood (minus Merrie Men). I wouldn’t have been surprised to see Billy the Kid put in an appearance in this kind of history-defying picture. In case you were unaware, or less of a pedant than myself, there were at least two centuries (possibly eight, depending on your sources) between monarch and outlaw. There’s a princess, but going by the more prosaic name of Katherine, rather than the legendary Guinevere, and for that matter Lancelot and Galahad are excused duty, though the wizard Merlin pops up.

I hate to break it to you, but there is no siege. But there is, as if this more than makes up for that omission, marauding Vikings. Or at least marauders pretending to be Vikings, or that might just be my fault, assuming that those helmets with the rounded pointy bits were the preserve of the Norsemen.

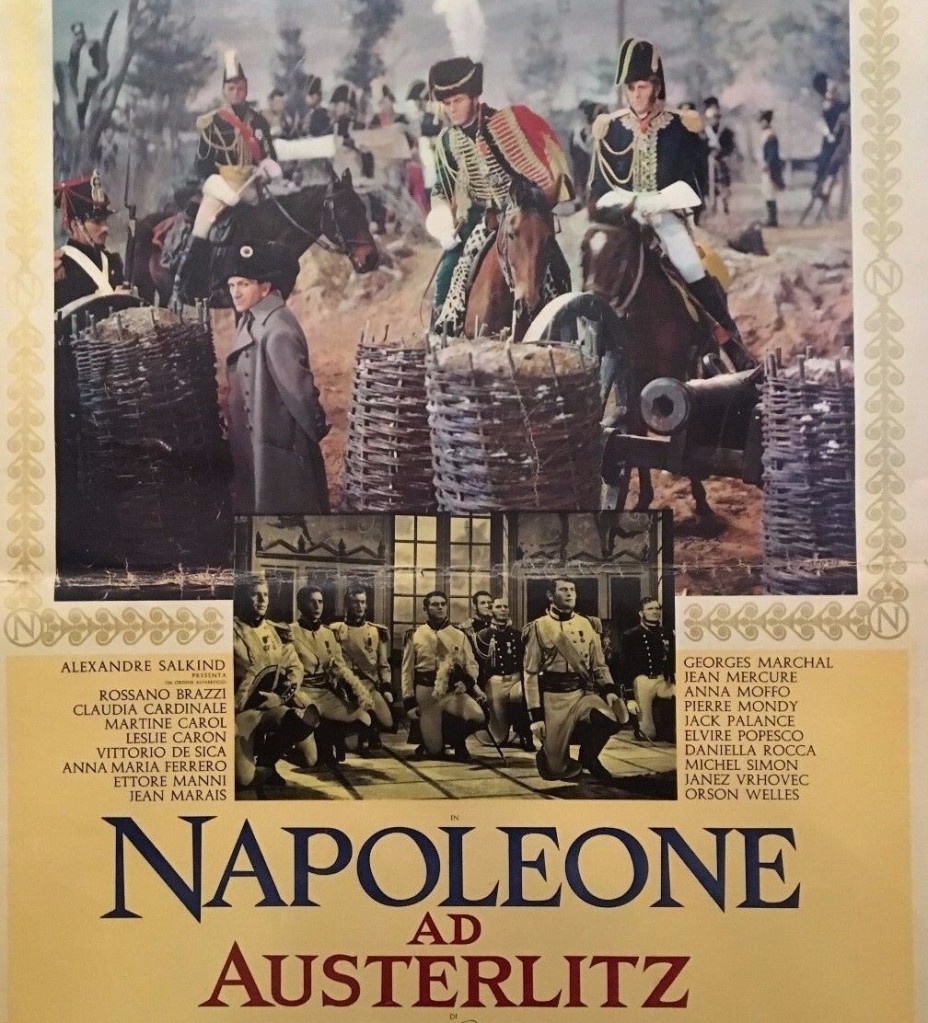

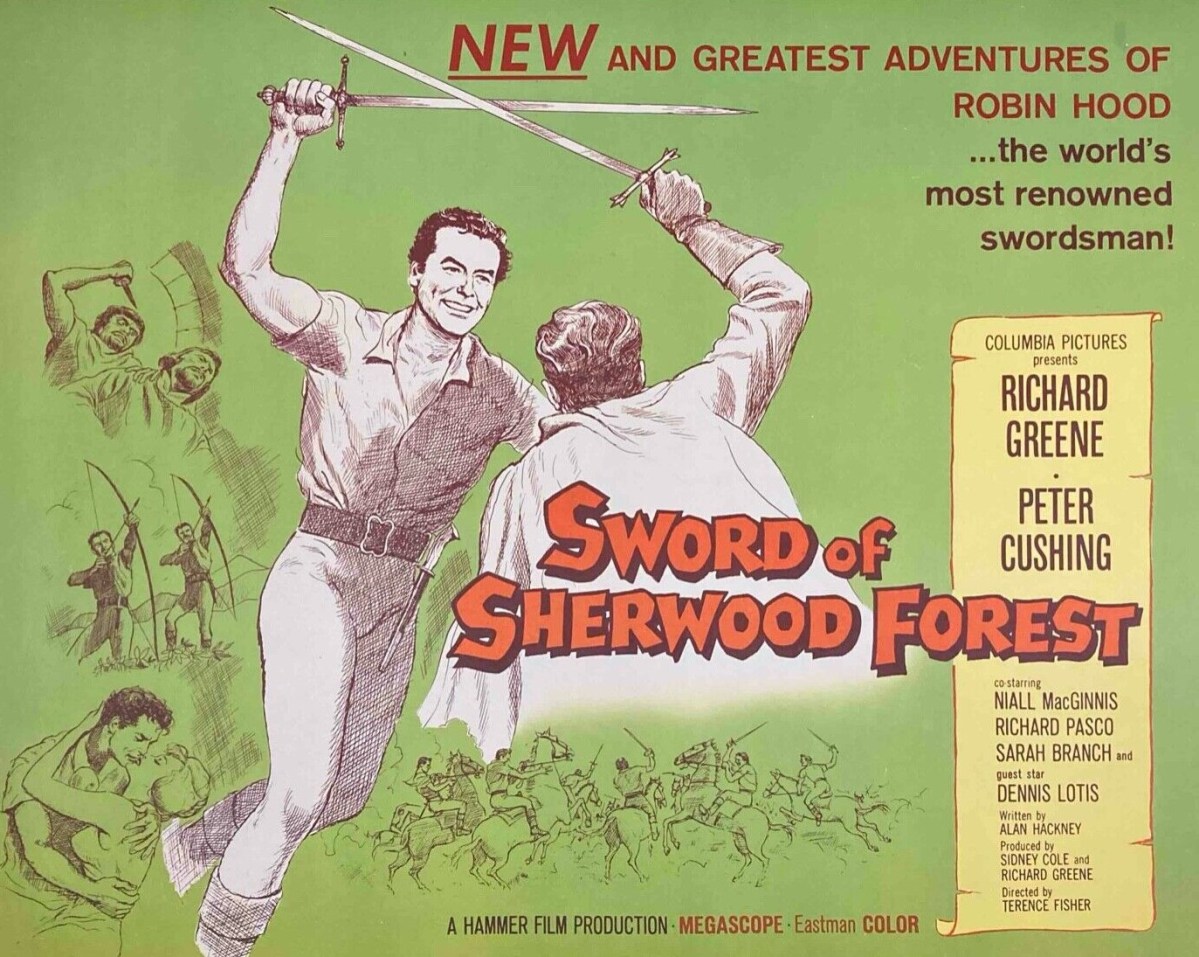

And, presumably, for legal reasons (“passing off” in the jargon and there being a British television series and Hammer film to contend with) Robin Hood isn’t called Robin Hood even though he’s an outlaw in a forest who robs the rich to give to the poor. His moniker is Robert Marshall. You’d need to be well up on your history to work out why the Saxons would be considered bad guys when England was populated by Anglo-Saxons.

But when I explain this is made by the same duo that plundered a stock footage hypermarket for East of Sudan (1964) you’ll probably agree that accuracy was not their strong suit. Which is a shame, because it’s a half-decent tale of treachery and revenge and gives the underrated Janette Scott (Paranoiac, 1963) a strong role.

Anyways, Edmund (Ronald Howard), dastardly lover of Katherine (Janette Scott), daughter of an infirm King Arthur (Mark Dignam), sets up Robert (Ronald Lewis) to take the fall for his murder of the sovereign via his anonymous henchman known as The Limping Man (Jerome Willis). Katherine is reluctant, naturally, to head off into the unknown with the outlaw, especially when he insists on disguising her (none too cleverly it has to be said) as a boy while they seek out Merlin (John Laurie) in the hope that his wizardry can muck things up for the imposter.

It’s a wasted journey, not because he’s not filled with the requisite wisdom, but if they’d just left things to Excalibur in the first place all would be sorted. You see, the villain hasn’t worked out there was a good reason that Arthur managed to yank said sword out of the stone in the first place. Edmund can pull at the sword until he’s blue in the face but it’s not going to shift out of its scabbard, because, well, he ain’t Arthur. Just as well Edmund deprived Arthur of the bedside dying scene beside the lake where the king could chuck it in to ensure nobody of the dastardly persuasion could take advantage of its magical powers.

But, aha, genetics enter the equation. You could have made an entire new film out of chasing down the King Arthur Code, but luckily we are too many decades away from that kind of malarkey. So – feminist alert – it’s Katherine who’s inherited the genes. And – woke alert – who should ascend to the throne alongside her but the outlaw.

So it’s fairly straightforward stuff, swordfights, chases, a battle or two, bad guys and good guys and resolutely old-fashioned except for the feminist climax. Just a shame that nobody can match Janette Scott’s screen charisma, so though Ronald Lewis (Nurse on Wheels, 1963) can deliver a one-liner with aplomb and cut a swathe through bad guys, he’s not in her league. This is B-picture stuff without the redemptive features of noir or general nastiness or maybe a future star director making an impact.

Nathan Juran (First Men in the Moon, 1964) directed from a script by Jud Kinberg (East of Sudan) and John Kohn (The Collector, 1965) loosely based on the work of Thomas Malory who dreamed up the Camelot repertoire.

Undemanding.