It was Hollywood’s worst nightmare. Two major studios – Columbia and Warner Brothers – were competing to make films about the Battle of the Bulge, one of the most famous episodes of the Second World War. Rival movies on similar or the same subject – classic examples You Only Live Twice (1967) vs Casino Royale (1967) or Deep Impact (1998) vs. Armageddon (1998) – risk cannibalising each other, each entry eating into the prospective audience of the opposition.

At first it seemed like the Columbia entry had the upper hand. Writer-producer Anthony Lazzarino had spent four years preparing The 16th of December: The Story of the Battle of the Bulge (the date referring to the start of the battle). Lazzarino’s project was endorsed by the U.S. Department of Defense which offered exclusive cooperation. Advisors were of the top rank – General Omar Bradley, General Hasso E. von Manteufel who had commanded the Panzers during the battle, British generals Sir Francis de Guingard and Robert Hasbrouck and Colonel John Eisenhower plus the cooperation of Eisenhower himself and Field Marshal Montgomery.

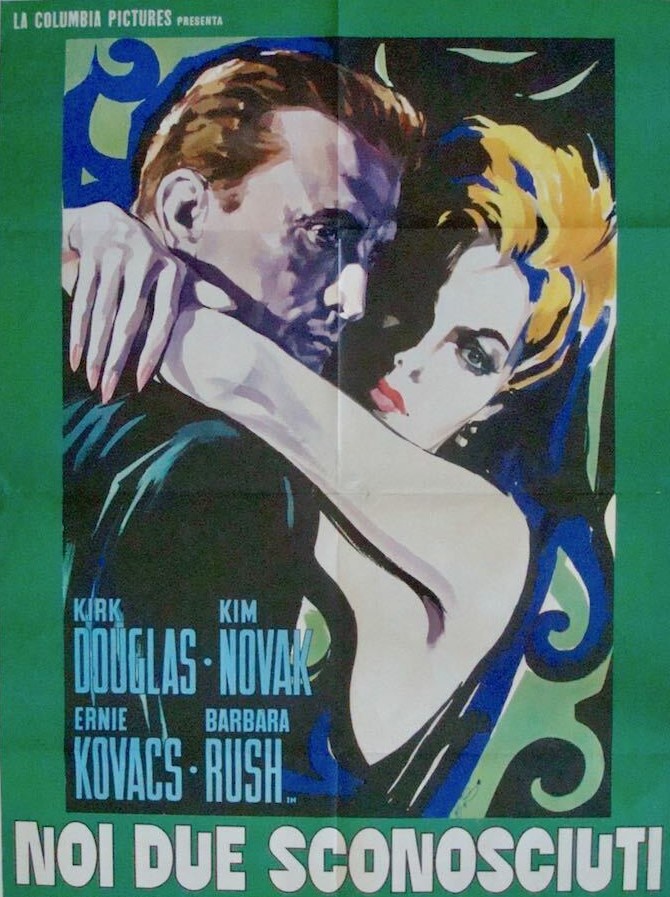

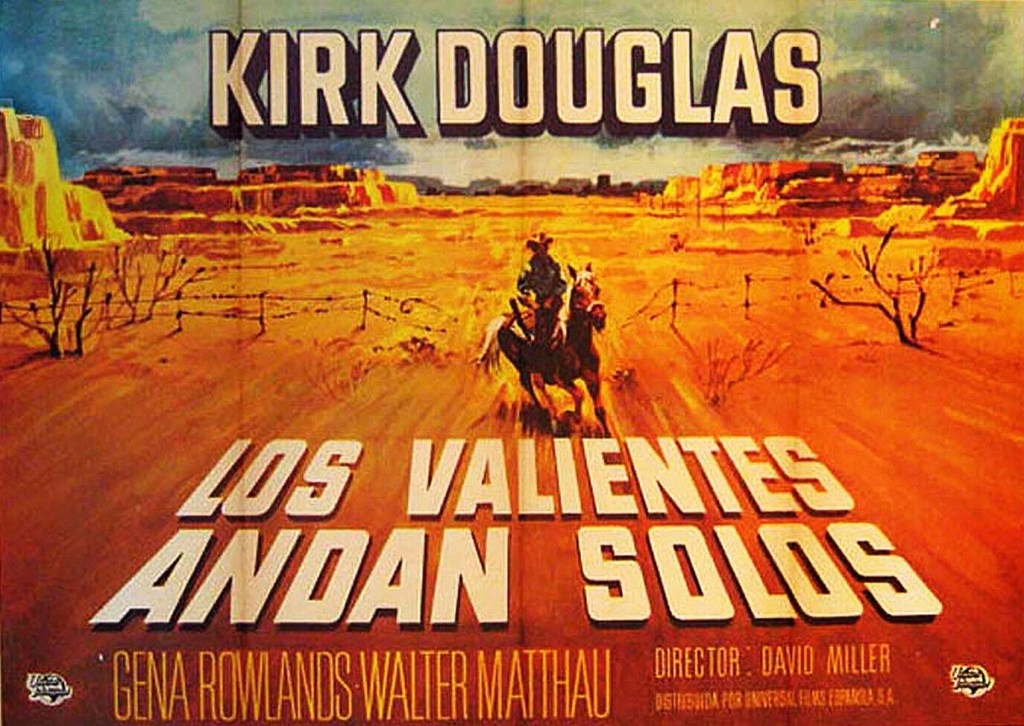

With a budget in the $6 million – $8.4 million range, and shooting was set to start in winter 1965, William Holden was lined up to play General Eisenhower and Kirk Douglas for General Hasso. Although initially intending to film in the Ardennes and Canada, ultimately the producers settled for the cheaper option of Camp Drum, one of the largest military installations in the U.S, a remote area in upper New York where the buildings could stand in for Bastogne, around which much of the real battle revolved, production there feasible because the Camp closed for winter. .

But that meant it would already be behind the eight-ball since Battle of the Bulge intended opening at Xmas 1965. Richard Fleischer (The Boston Strangler, 1968) was originally signed to direct. But he had become embroiled in a lawsuit with producer Samuel Bronston (El Cid, 1961, The Fall of the Roman Empire, 1964) whose production outfit had gone bust, killing off a deal for Fleischer to make The Night Runners of Bengal. The director was seeking g $910,000 in compensation.

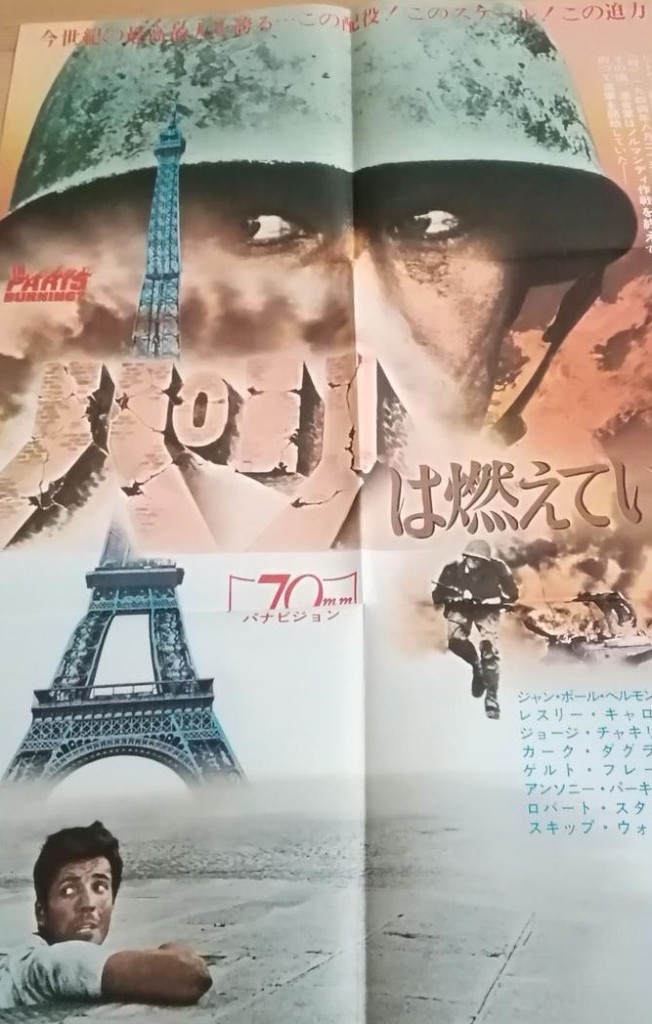

Warner Brothers had enlisted Cinerama as co-producer, the studio’s first involvement in the stunning widescreen process and the first time war was considered a subject. The process had been utilised in other Hollywood pictures most notably MGM How the West Was Won (1962), but that has been as a supplier of the equipment, and taking a small share of the profits. But now Cinerama planned to enter the production business and had contracted with WB to shoot the film in the single-lens process instead of the more complicated three-camera approach which had led to vertical lies on screens.

Neither company was in great shape. Cinerama had posted a $17.9 million loss in 1964, WB $3.8 million. But whereas WB had My Fair Lady on the horizon, Cinerama was less reaons for optimism. Its income stream relied on sales of its equipment, either for filming or projection, and a levy from every cinema using the process. Expansion was seen as key to renewal. With only 67 cinemas equipped to show Cinerama in the U.S. and only 59 overseas, a major program was underway to reach 230 by 1967. Setting up a production division would ensure there were enough films to feed into Cinerama houses, and since such films were intended as roadshows, they would keep the cinemas product-secure for months on end.

Cinerama planned to spend $30 million on five films – John Sturges western The Hallelujah Trail (1965) budgeted at $5 million, Battle of the Bulge ($.75 million) while $6.5 million had been allocated to an adaptation of James Michener bestseller Caravans, $6 million for Beyond the Stars which became 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and $7 million for Grand Prix (1966). Added to the list was epic William the Conqueror, due to film in England in early 1966 with Robert Shaw taking top billing.

The WB-Cinerama project, which had taken a year to negotiate, was to be filmed in Spain under the aegis of producer Philip Yordan, one time associate of Bronston who had built a mini-Hollywood there. Yordan, Bronston’s chief scriptwriter, had written the screenplay along with his co-producer Milton Sperling. Instead of seeking official support or reproduce the battle in documentary detail, Yordan and Sperling aimed for a fictional account that took in the main incidents. The cast would include “ten important stars.”

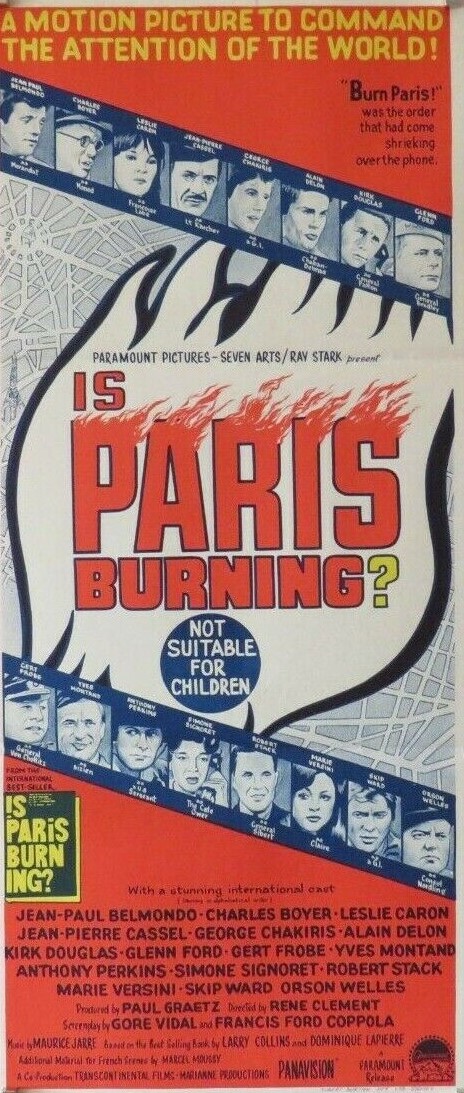

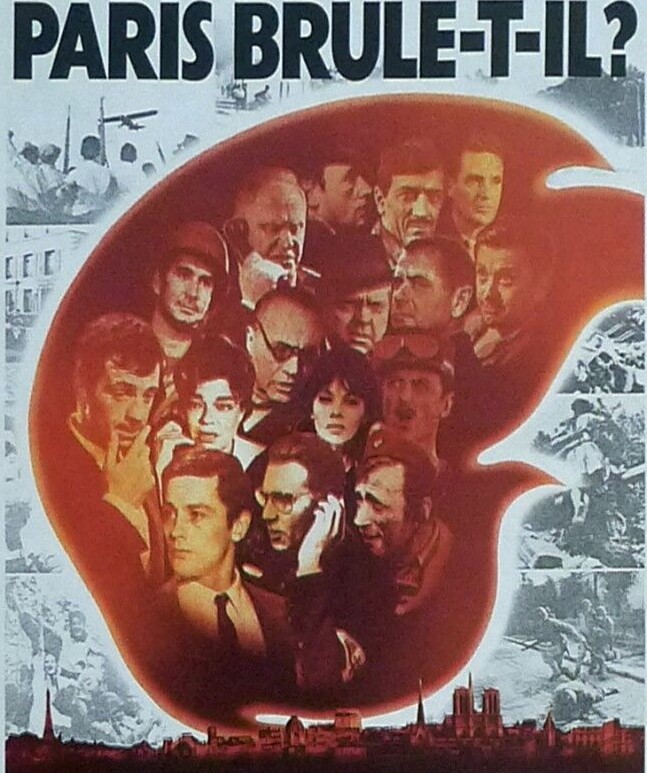

Just what constituted an “all-star cast,” one of the key ingredients of the roadshow phenomenon of the 1960s, was open to question. While The Longest Day (1962) boasted stars of the pedigree of John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, Richard Burton and Sean Connery, it was also liberally sprinkled with actors of no marquee value. David Lean in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) had loaded his film with the likes of Oscar winners Alec Guinness, Anthony Quinn and Jose Ferrer to offset unknowns Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif as the leads. While The Great Race (1965) could boast Jack Lemmon, Tony Curtis and Natalie Wood, It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) only had Spencer Tracy amid a host of television comedians.

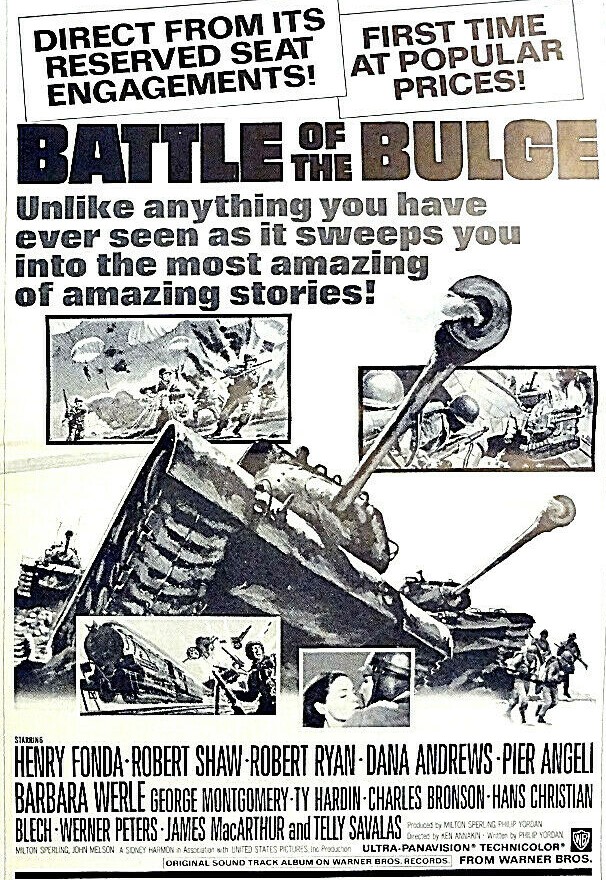

But none of the stars of Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1964) had successfully opened a major picture. Of the Battle of the Bulge contingent only Henry Fonda could truly be called a current star, although his box office star had considerable dimmed since the days of The Grapes of Wrath (1939) and Fort Apache (1948). Former stars Robert Ryan and Dana Andrews were now supporting actors, Ty Hardin was best known for television, Charles Bronson (The Great Escape, 1963) had not achieved top billing and while James MacArthur had done so that was in youth-oriented movies. Initially, Italian prospect Pier Angeli (Sodom and Gomorrah, 1962) was announced as “the only principal female role” – playing a Frenchwoman – for a touching scene showing the effect of war on innocent women caught up in the conflict.

Just before filming was about to start, Fleischer pulled out, citing differences of opinion with the producers. Yordan turned to British director Ken Annakin, who had helmed the British sequences in The Longest Day and Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines. There was soon a double whammy. Realizing he was losing ground, and hoping to sabotage its progress, Larrazino sued WB for $1 million, claiming that “another film, less accurate, would be confused with his picture.” Just as filming of the Battle of the Bulge got underway in January 1965, it was hit by a temporary restraining order. While failing to shut down the production, it imposed a marketing blockade. WB was prevented from publicising its picture, a potentially major blow given how dependent big budget roadshows were on advance bookings which could only be generated by advance publicity.

Annakin’s immediate response to the opportunity was delight. He commented that he had a “lot of toys to play with.” He found inspiration for his approach from an unusual source, the Daleks (“an apparently irrevocable onslaught of metal monsters”) from the BBC television series Dr Who. He decided he would use Cinerama as “a kind of 3D, shooting in such a way that the tanks would loom up as monsters against humans whom I would make small and puny.”

Although he had no influence in the casting, Annakin was already familiar with some of the actors, James MacArthur from Swiss Family Robinson (1960) and Werner Peters and Hans Christian Blech from The Longest Day. He did not receive such a warm welcome from Robert Shaw whom he had rejected for a role in The Informer.

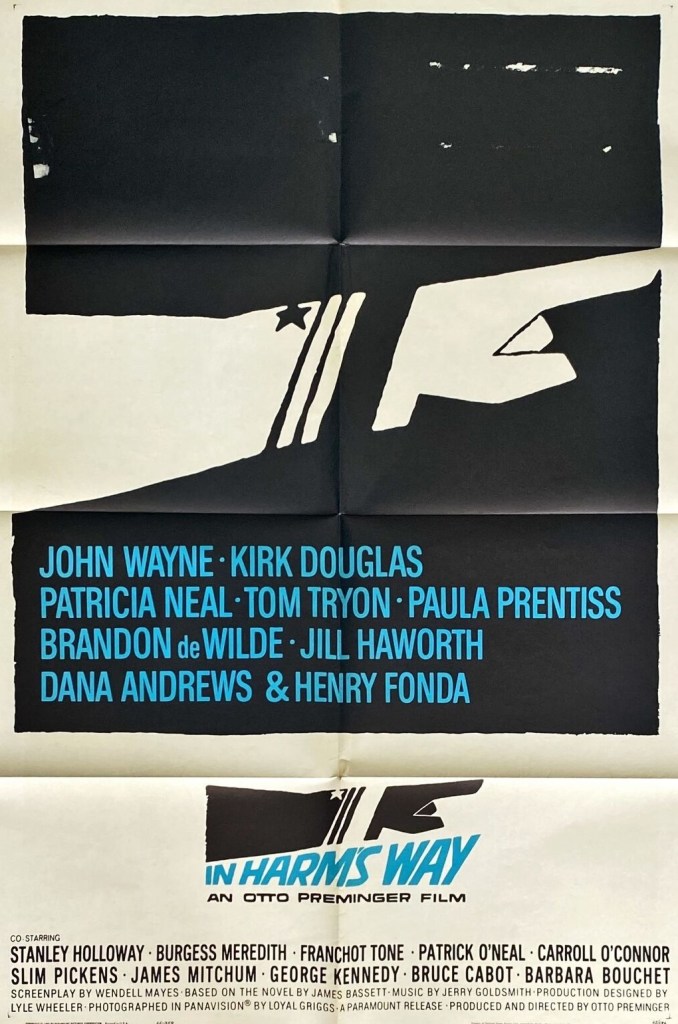

He found Fonda “a remarkable professional…always on time, patient, eager to get to work, and always knew his lines.” He confessed to being a reluctant movie actor, preferring the stage, and had not been a big office draw since his work with John Ford in the 1930s and 1940s. Even critical successes like Twelve Angry Men (1957) had lost money, some of it the actor’s own, and prestige movies like The Best Man (1964) and Fail Safe (1964) failed to attract sufficient audiences. “In the theatre,” he said, “the actor achieves fulfilment from beginning to end. But on a picture you create a minute here and a minute there over a twelve-week period. When it’s finished there’s no recollection of what you did…Films are a director’s medium.” Battle of the Bulge was his 59th picture, after completing a supporting role in Otto Preminger’s In Harm’s Way (1965) and taking second billing to Glenn Ford in modern western The Rounders (1965).

There was a stand-off with Bronson on his first day after the actor kept the crew waiting while fiddling too long with his costume. Ty Hardin (television’s Bronco, 1958-1962) was accident-prone, tumbling into a frozen river in full kit, and whacking the director’s wife in the face with his helmet. Dana Andrews had a drink problem so that in some scenes Fonda and Ryan would be surreptitiously holding him up. But such veteran actors could improvise their way round scenes and “give me hints and lead me into changes.”

Andrews was enjoying career resurgence. His movie career was at a standstill, a ong way from a peak like Laura (1944). But his last significant top-billed parts were over a decade gone. “I was starting to get nothing for a while but offers came swarming in when I told my agent to go ahead and try from Walter Huston parts.” After only televisions roles in the four years since Madison Avenue (1961), Battle of the Bulge would mark his eighth role in 1965, including The Satan Bug and In Harm’s Way.

Winter in Spain was cold which meant it provided the ideal backdrop for the WB version. The chosen location, 4,500ft high in the mountains of Segovia provided identical conditions to the actual battle. Spain had provided 80 tanks including Tigers mounted with 90mm guns and Shermans. Half of the 20-week shoot would be spent in Segovia with interiors filmed at studios in Seville and the Roma facility in Madrid. The WB adviser was General Meinrad von Lauchert, a divisional tank commander during the battle. He hoped the picture would show the German solider “as he was, brave and good” rather than clichéd presentation and not give the “impression that the American Army had nothing to do but walk into Germany.”

He wanted the film to reflect the truth that the “Americans had to pay a high price for every yard.

Extras were drawn from the Spanish village of El Molar, with a population of just 2,400, which specialised in that supply. Locals could earn 200 pesetas a day. A pair of tavern owners had established this lucrative side-line, demand so high at this point that “they can play Russian World War One Deserters for Doctor Zhivago (1965) one day and shipped to World War Two the next for Battle of the Bulge.” Whenever Annakin found himself in trouble with the script he turned to the senior actors, Fonda, Ryan and Andrews who could improvise their way round scenes and “give me hints and lead me into changes.”

For the first scene, a week’s worth of white marble dust, representing snow, had been spread over the ground before 40 tanks emerged from a pine forest. But just as the cameras begun to turn, unexpectedly, against all weather forecasts, it began to snow. While initially a boon, when it continued to fall for five weeks the snow turned into a liability. Nobody was prepared for snow, not to the extent of snowploughs or even salt and it was a three-mile hike uphill to reach the tank location until army vehicles could be used to transport the crew. The tanks churned up so much mud that three or four cameras were required to catch the action.

“It was a director’s feast,” recalled Annakin, salivating about the prospect of a “vast panoramic” employing the entire array of tanks. To speed production, he had two units one hundred yards apart and jumped from one to the other, thus achieving 30-40 set-ups a day while the effects team exploded tubes and burned rubber tyres to create a fog of black battle smoke. A small town, already wrecked and shelled from the Spanish Civil War, added an air of realism when standing in for Bastogne.

Midway through shooting the producers realised the movie lacked a theme and from then on Annakin was faced with daily rewrites as new scenes were added to bring out the humanity implicit in war. Then Cinerama boss William Foreman arrived and demanded the insertion of the type of shot he believed his audiences were expecting, the equivalent of the runaway train and the ride through the rapids in How the West Was Won. He angled for a jeep racing downhill or a plane spinning and diving and happy to stump up any extra costs.

Such a request was more easily accommodated than his insistence that a role be found for his girlfriend Barbara Werle. a bit part actress Tickle Me (1965). While Yordan, wearing his producer’s hat, was willing to keep one of his main funders happy, the director and Robert Shaw were not. Shaw refused to do the scene until Foreman pleaded with both, explaining that in a vulnerable period of his personal life – when, in fact, he had been imprisoned – Werle had helped him out and he owed her a favour.

In Annakin’s opinion Werle was “willing but completely dumb…as though you had picked a girl straight from the cash desk of a supermarket.” Her one scene, as a courtesan offered to Robert Shaw by a grateful superior, was used to mark out the German commander as a man of honour when he rejection such temptation out of hand.

To overcome problems of matching earlier Panzer footage with the climactic battle to be shot on the rolling hills of Campo – in the earlier shots the ground was covered in snow, but now it was summer and the ground was scorched by the sun – Annakin relied on aerial shots, shooting downwards, “keeping as close as possible so as not to reveal what the terrain actually looked like” while on the ground two units shot close-ups of the action. The action was augmented by 30 model shots with miniature explosions.

When shooting was completed, there was a race to get the movie ready for its schedule launch, on December 16, 1965, the 21st anniversary of the start of the battle. There were ten weeks left to do post-production. Four editors had already been working on the material but Yordan asked Annakin, who had not been near a moviola for two decades, to personally edit the climactic battle scene. The director found the experience exhilarating: “matching my location footage with miniature shots; a four-foot helicopter (i.e. aerial) shot cut with a couple of feet of a U.S tank rounding rocks to face a Panzer; a shot of Telly Savalas at his gun site yelling ‘Fire’ intercut with a miniature tank blowing up.” But all his intricate work never made it into the final cut. Another editor fiddled around with the material and since no one had thought to make a dupe of Annakin’s original it was lost.

Although the challenge from Lazzarino had died away, the Pentagon was unhappy with the amount of time allocated to the German perspective. Yordan had the perfect riposte, pointing the finger at Annakin and saying “see what happens when you get a limey director.”

Werle had the last laugh. She was billed sixth in the credits (Angeli came fifth) but in the same typeface as Fonda, Shaw, Ryan and Andrews, and above the likes of Bronson, MacArthur and Hardin who not only all had substantially greater screen experience but had a bigger impact in the movie.

With the smallest part of all the listed stars, nonetheless she managed to turn the experience to her advantage, introduced to the press part of the marketing campaign and attending the world premiere at the Pacific Cinerama on December 16, 1965 in Los Angeles and the New York premiere the following day, brought forward four days, at the Warner Cinerama. In Los Angeles she arrived in true style at the head of a marching brigade of 100 service men.

SOURCES: Ken Annakin, So You Wanna Be A Director (Tomahawk, 2001) p167-181; “Du Pont, Bronston, Co-Defendants,” Variety, July 22, 1964, p4; “Schenck-Rhodes Roll Battle of Bulge at Camp Drum in U.S.” Variety, July 22, 1964, p42; “German Military Sensitivity,” Variety, September 23, 1964, p32; “Columbia Will Distribute Battle of Bulge Film,” Box Office, September 28, 1964, p18; “Plan Battle of Bulge As Cinerama Film,” Box Office, November 23, 1964, p4; “Tony Lazzarino To Produce The 16th of December,” Box Office, December 16, 1964, p4; “Rival Battles of Bulge; Bill Holden Up for Ike in Lazzarino Version,” Variety, December 16, 1964, p5; “Warner Reports Loss of £3,861,00,” Variety, December 23, 1964, p5; “L.A. Court Has Its Battle of Bulge Hearing, 27th,” Box Office, January 25, 1965, pW-2; “Dana Andrews Strategy: Regain Momentum,” Variety, March 10, 1965, p3; “Battle of Bulge Now Being Lensed in Spain,” Box Office, March 15, 1965, pNE2; “Winter in Spain Cold But Correct for Bulge Pic,” Variety, March 17, 1965, p10; “Cinerama Plans Five Films to Cost $30 Mil,” Box Office, April 19, 1965, p13; “For Actor Satisfying Legit Still Beats Pix, Reports Henry Fonda,” Variety, May 3, 1965, p2; “London Report,” Box Office, May 3, 1965, p8; “One Girl in WB Bulge,” Variety, May 5, 1965, p20; “Battle of Bulge Pic May Roll Next Winter,” Variety, May 5, 1965, p29; “El Molar, Spain’s Village of Extras,” Variety, May 12, 1965, p126; “Cinerama Report Loss,” Variety, May 13, 1965, p15; Advert, Box Office, July 12, 1965, p22; “WB To Film Cinerama Epic in England,” Box Office, October 11, 1965, p11; “Introduce Barbara Werle,” Box Office, October 18, 1965, pE3; “Battle of Bulge Opens N.Y. Now Dec 21,” Box Office, October 18, 1965, p10; “Actress To Attend Bows of Bulge in L.A., N.Y.,” Box Office, December 6, 1965, pW4.