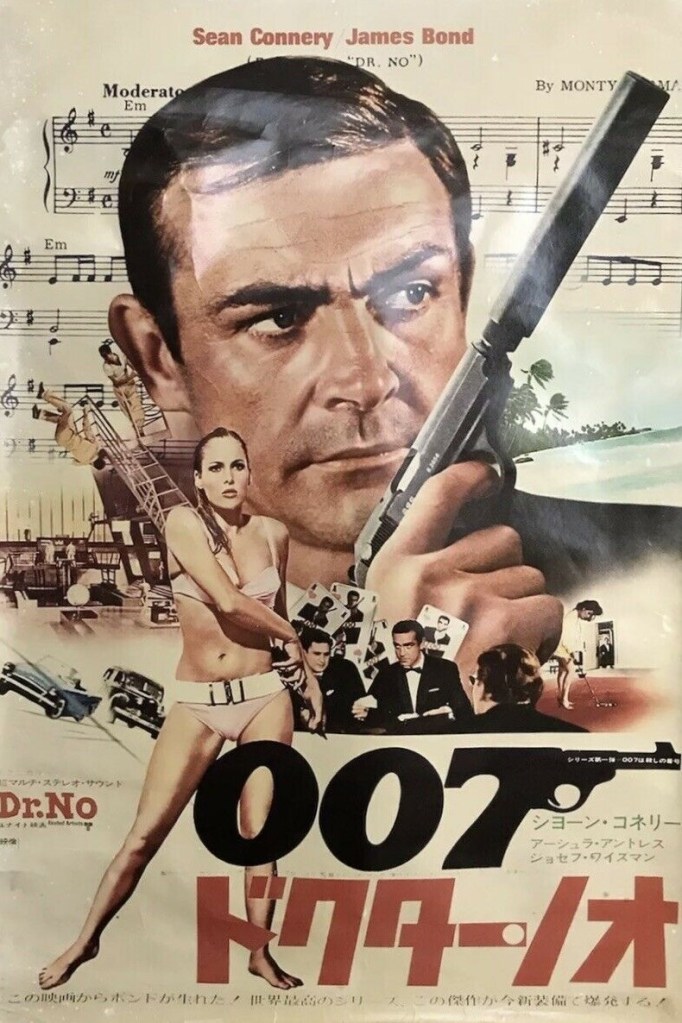

Half a century ago it would have blasphemy to do anything but mock this oh-so-obvious James Bond rip-off. That was the year, if you remember, when another bigger-budgeted spoof, Casino Royale, took an almighty chunk out of the box office of You Only Live Twice. Where the former had a multitude of Bonds, Operation Kid Brother settled for the premise that its main character was the brother of the famed secret agent.

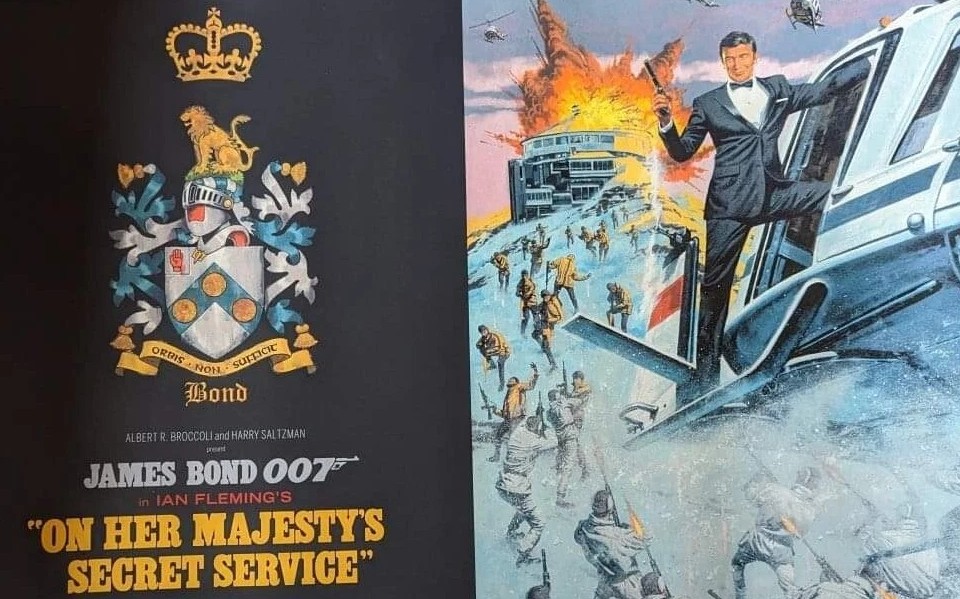

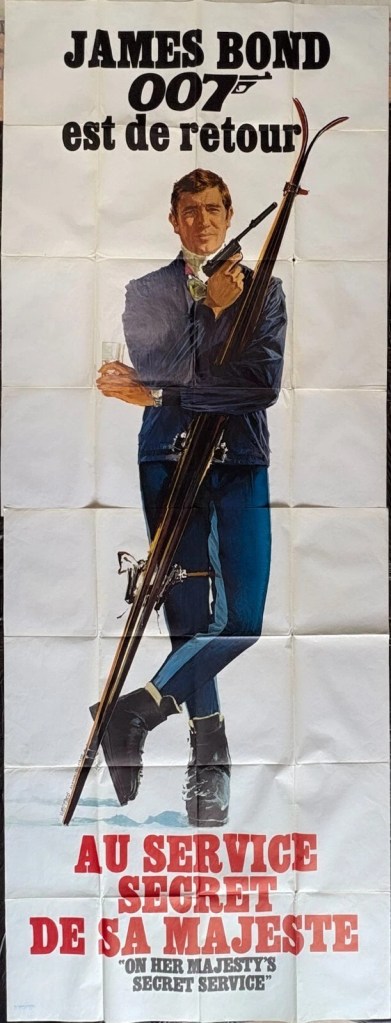

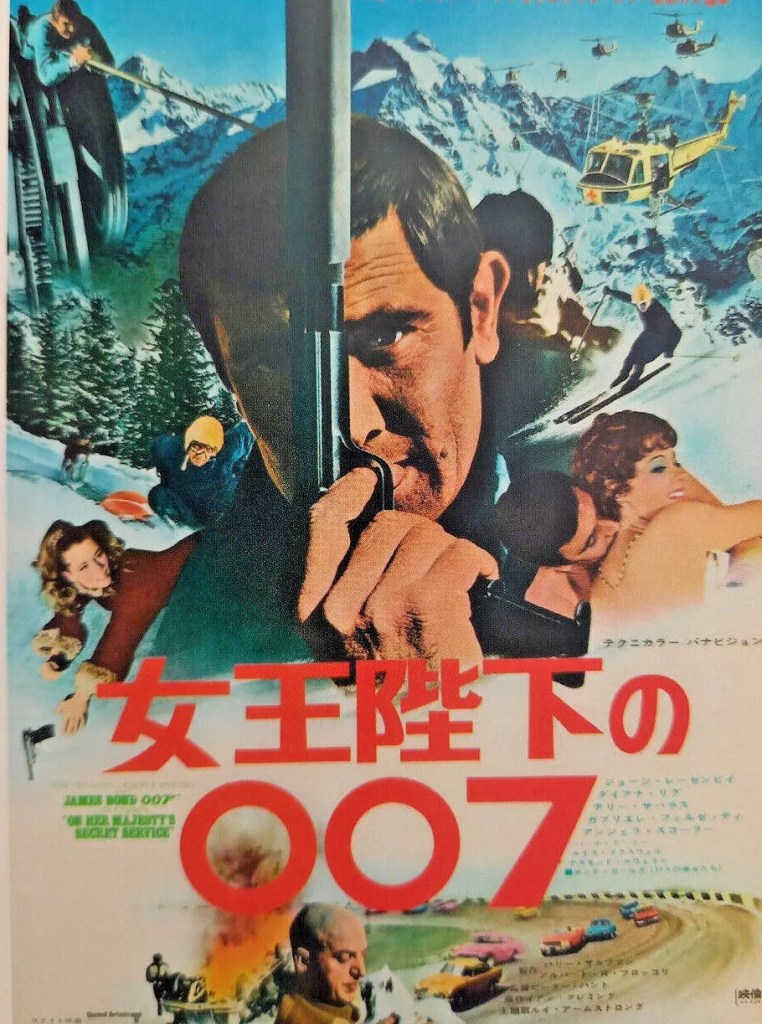

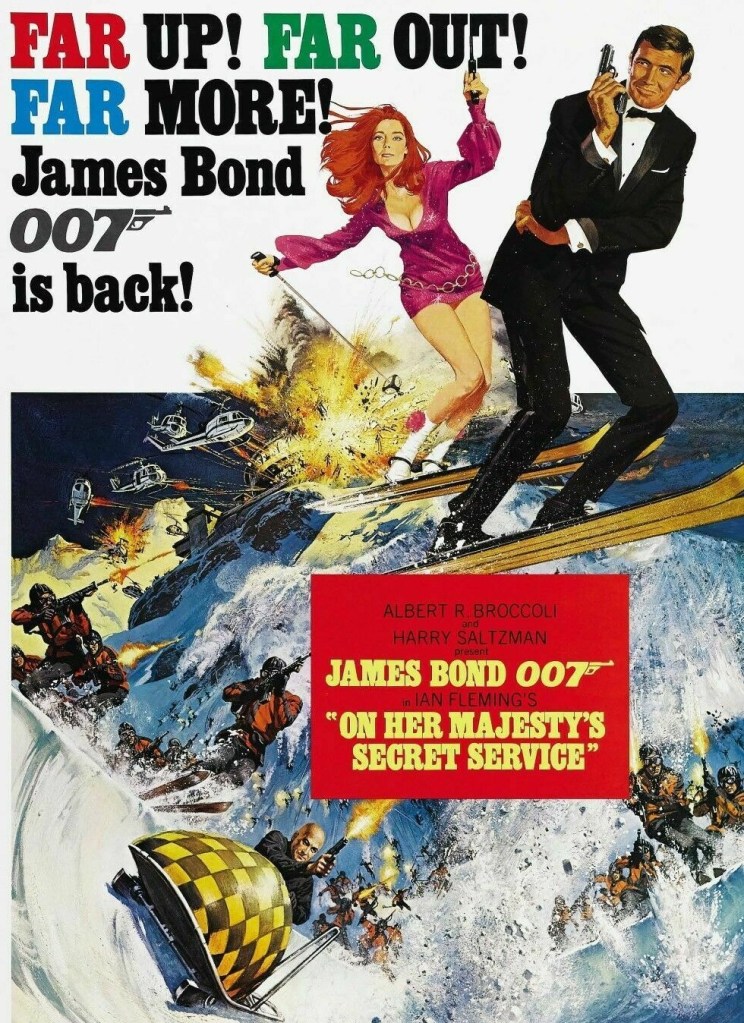

Far from being a disaster, it is, to use the alternative title, “O.K.”, and in parts more than acceptable, especially in its anticipation of ideas that would later become Hollywood tropes: packages concealed in the brain (Total Recall, 1990 and Johnny Mnenomic, 1997), driverless cars (from The Love Bug, 1968, to Tomorrow Never Dies, 1997, and beyond), electronic global blackout and its current equivalent the gravity wave (Moonfall, 2022), and even a poison ploy that popped up in The Princess Bride (1987). Perhaps you could also reference The Bourne Identity (2002), the newspaper weaponized there could be traced back to the harmless belt here. And if you want to get really contemporary – the hero has a superpower: hypnotism. Bear in mind too that sly references to “the other guy” were made in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), the first in the series not to feature Sean Connery.

Dr Neil Connery (Neil Connery) belongs to the sub-genre of innocents caught up in espionage (Hot Enough for June, 1964). As with the main character, this is more of an affectionate pastiche of the Bond films than any attempt to make fun of the series. This Connery is a plastic surgeon from Edinburgh (birthplace of his real-life brother Sir Sean) who has invented a method that permits secrets to be carried inside the brain – in essence viewed as an “impregnable safe.”

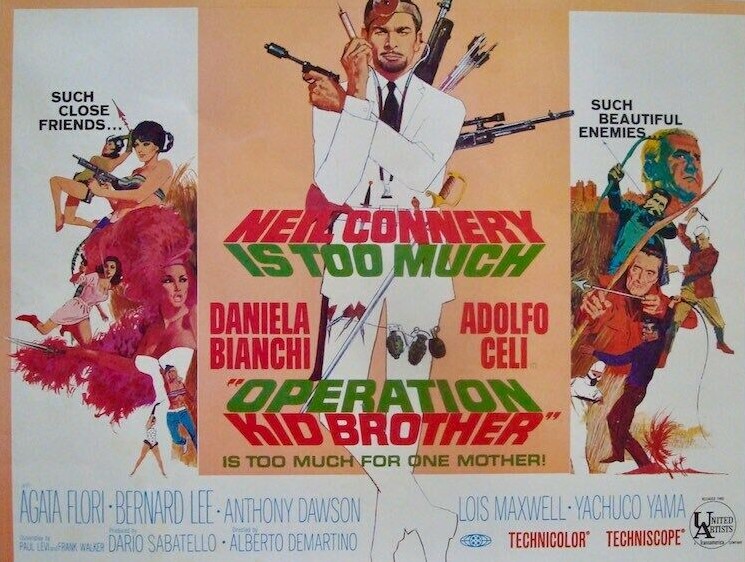

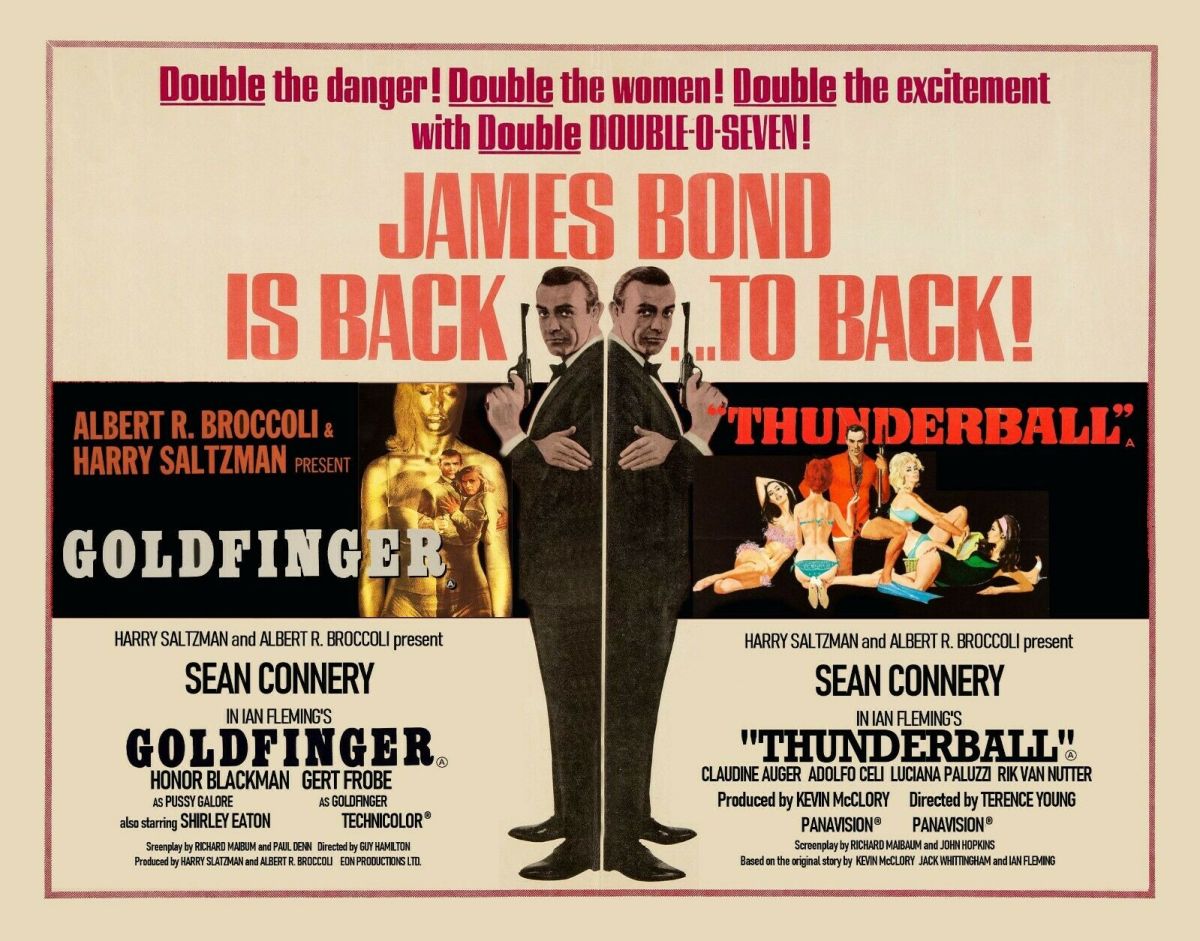

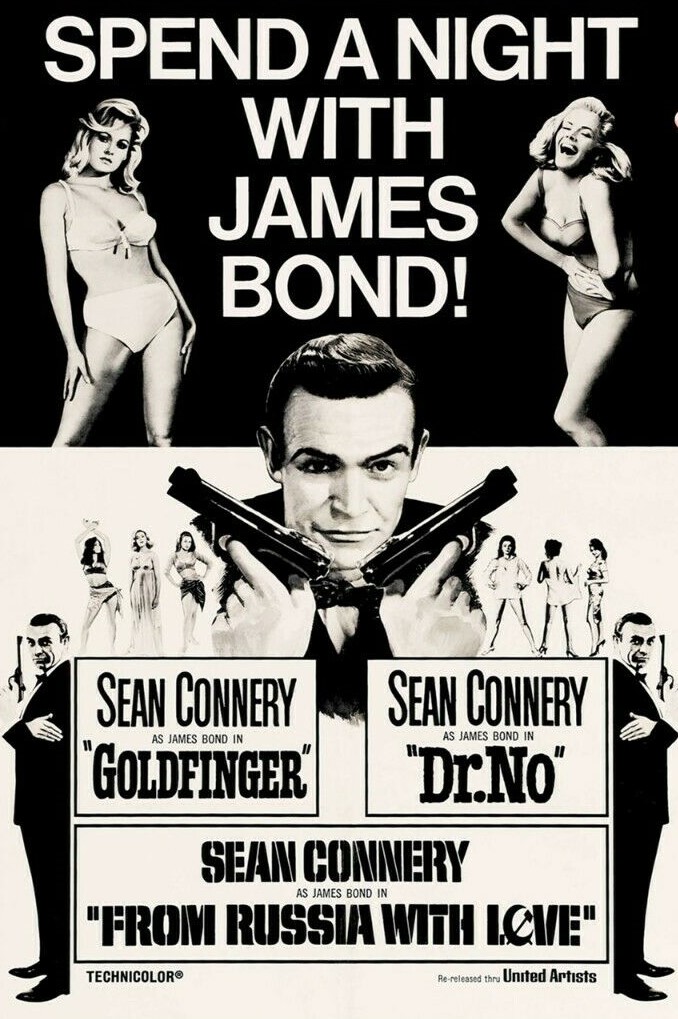

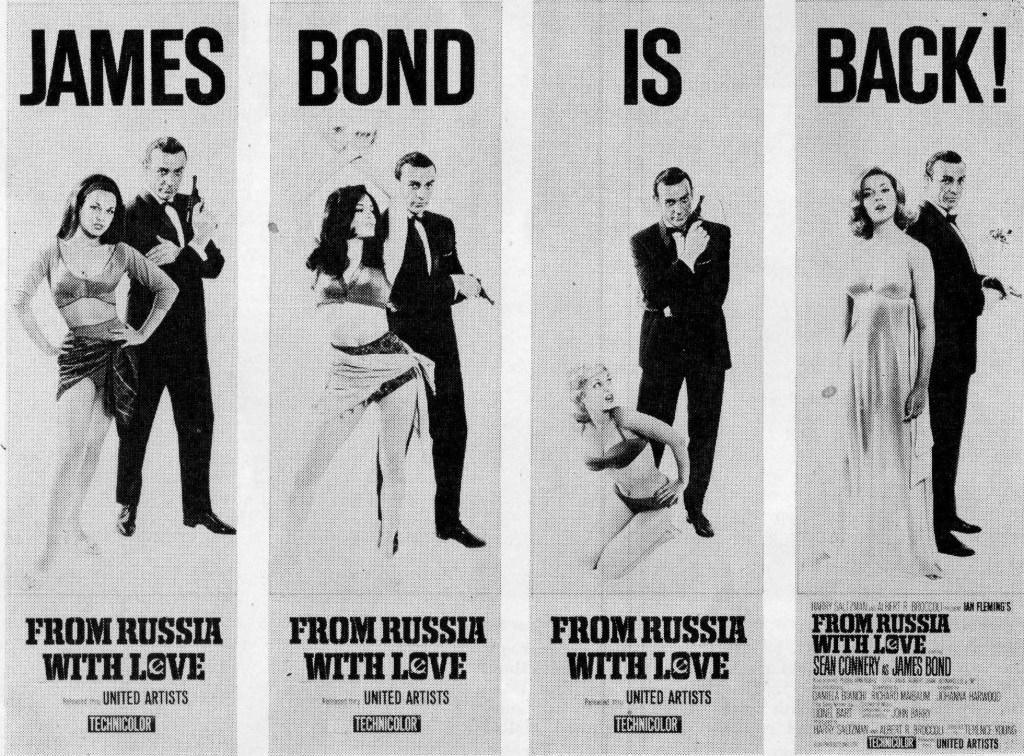

Bond alumni include Adolfo Celi (Largo in Thunderball, 1965), Daniela Bianchi (From Russia with Love, 1963), Anthony Dawson (Blofeld in From Russia With Love), Bernard Lee (M in the original series) and Lois Maxwell (Miss Moneypenny). Apart from a villainous female gang masquerading as the Wild Pussy Club, a reference to Pussy Galore in Goldfinger (1964) and a few sly references to the brother, the film is played straight.

Megalomaniacs Alpha (Anthony Dawson) and Beta (Adolfo Celi) belong to secret organization Thanatos intent on global domination by stealing atomic nuclei that will send magnetic waves across the world. Using intellect more than brawn, and with a sideline in lip-reading, Connery becomes involved because he can unlock the secrets hidden in the mind of Yachuko (Yee-Wah Yang), who is then kidnapped by Maya (Daniela Bianchi).

The costumes are slightly outre, Beta out of his depth in red leather, Maya in a hazard suit, Connery susceptible to kilts while Beta’s female yacht crew are decked out (pardon the pun) in tartan mini-skirts and pompoms. There is clever reversion to old-fashioned weaponry as archers assemble to assault the lair.

But all in all it is enjoyable. Yes, some of the pleasure derives from the twists on the Bond clichés, but Connery, complete with his brother’s pursing of the lips, is a decent enough stand-in. Daniela Bianchi (Special Mission Lady Chaplin, 1966), Adolfo Celi (In Search of Gregory, 1969) and the no-longer-deskbound Lois Maxwell (The Haunting,1963) join in the fun without making fun of the concept.

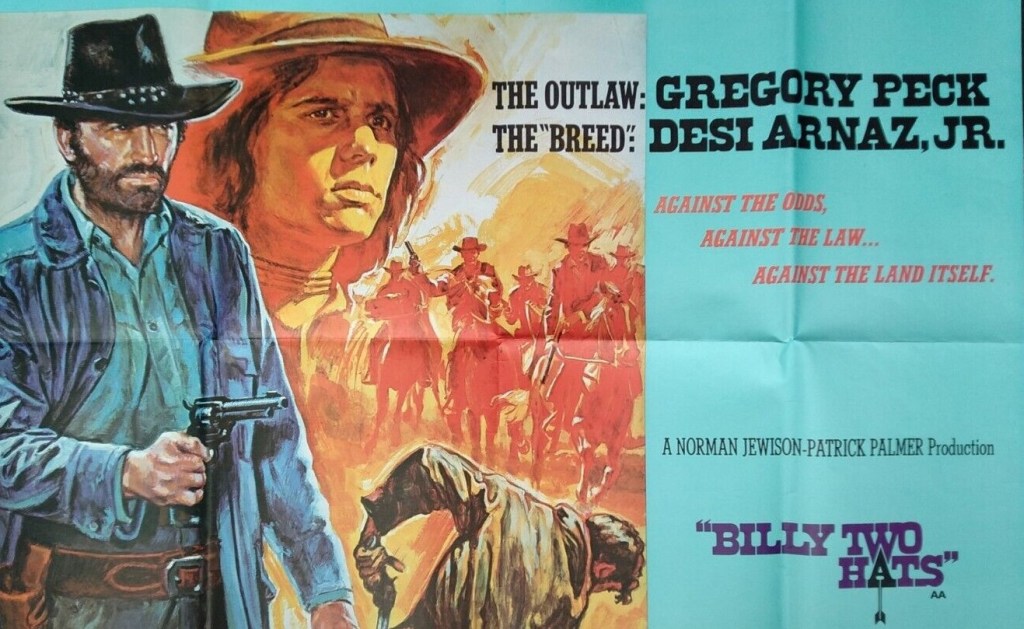

The direction by Alberto De Martino (Dirty Heroes, 1967) is competent but in the absence of a bigger budget perhaps exhilaration is too big an ask. The typical Italian production technique of lip-synching once the movie is completed does distance the picture. Three writers stitched the enterprise together – Frank Walker, in his only screenplay, Stanley Wright (Marenco, 1964) and Paulo Levi (Seven Guns for the MacGregors,1967).

Ebay is your best bet for a DVD of this one.

Check out also the “Behind the Scenes” article on this picture.