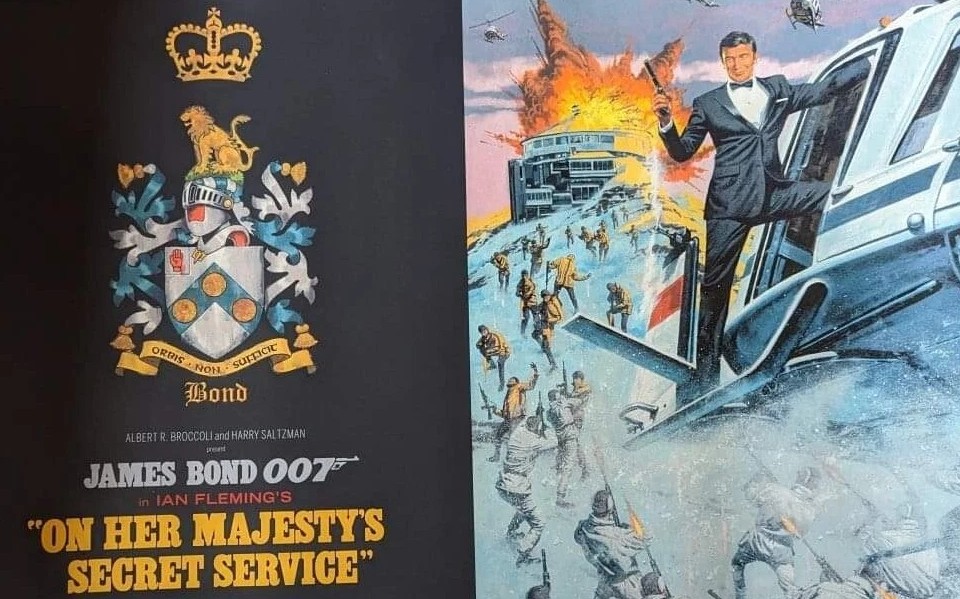

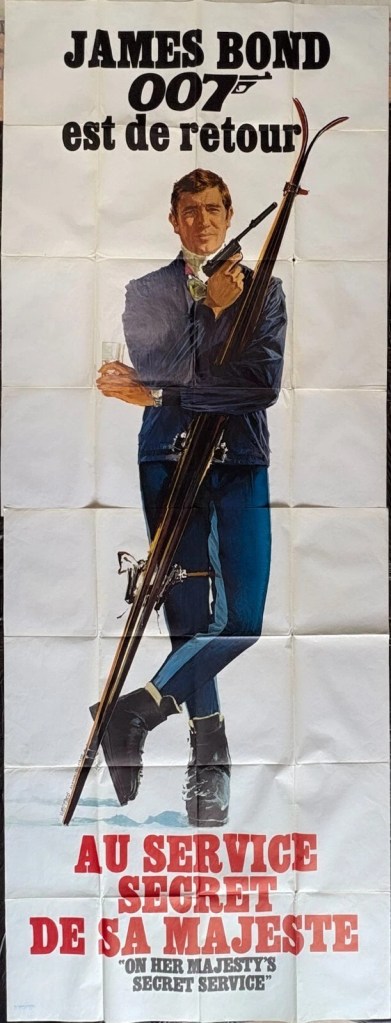

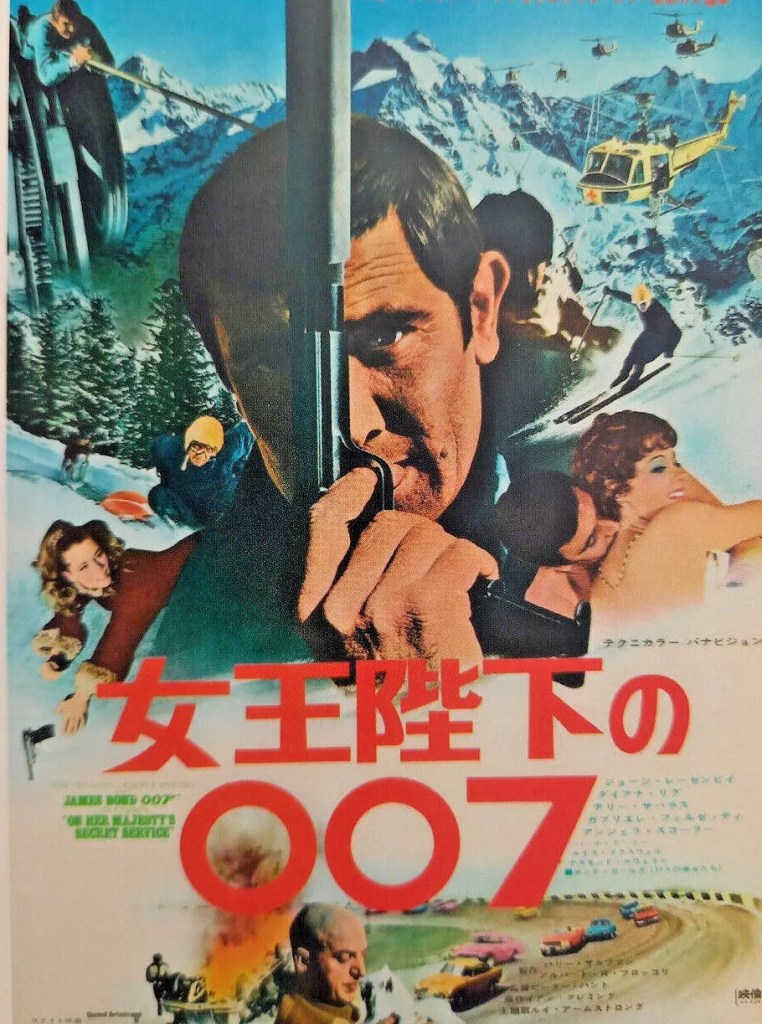

Holds a special place in my movie heart because it was the first James Bond film I ever saw and the first soundtrack I ever bought. Having, by parental opposition, been denied the opportunity to see any of the previous instalments and therefore having little clue as to what Sean Connery brought to the series I wasn’t interested in the fact that he had been replaced. I can’t remember what my younger self thought of the downbeat ending but on the current re-view felt that a rather cursory storyline was only saved by the stunning snow-based stuntwork, two races on skis, one on a bobsleigh, car chase on ice and the kind of helicopter framing against the sun that may well have inspired Francis Ford Coppola in Apocalypse Now (1979).

The heraldic subplot bored me as much to tears as it did the assorted dolly birds (to use a by-now-outlawed phrase from the period) and I was struggling to work out exactly what global devastation could be caused by his brainwashed “angels of death” (the aforementioned dolly birds). This is the one where Bond threatens to retire and gets married. Given the current obsession with mental health, the bride has a rather more contemporary outlook than would have been noted at the time. We are introduced to her as a wannabe suicide. Good enough reason for Bond to try and rescue her from the waves, and her mental condition not worthy of comment thereafter.

Turns out she’s the feisty spoiled-brat daughter Tracy (Diana Rigg) of crime bigwig Draco (Gabriele Ferzetti) and Bond persuades that Mr Big to help him snare the bigger Mr Big Blofeld (Telly Savalas), hence the convoluted nonsense about heraldry. There’s the usual quotient of fisticuffs and naturally James Bond doesn’t consider falling in love with Tracy as a barrier to seducing a couple of the resident dolly birds.

I takes an awful long time to click into gear but when it does the stunt work – perhaps the bar now having been raised by Where Eagles Dare (1968) – is awesome. Apart from an occasional bluescreen for a close-up of Bond, clearly all the chases were done, as Christopher Nolan likes to say, “in camera.” And there’s about 30 minutes of full-on non-stop action.

Pre-empting the future eyebrow-raising antics of Roger Moore, I felt George Lazenby was decent enough, bringing a lighter touch than Connery to the proceedings without his inherent sense of danger (which Moore also lacked). Diana Rigg, I felt was miscast, more of a prissy Miss Jean Brodie than a foil for Bond, even if this one was a substitute for the real thing. It was a shame Honor Blackman in Goldfinger (1964) had taken the slinky approach but that would have worked better to hook Bond than earnestness.

I’m not entirely sure how Blofeld planned to employ his angels of death but the prospect of a gaggle of dolly birds gathering in fields or rivers and being capable of distributing enough toxic material to destabilize the world seems rather ill-thought-out.

Theoretically, this is meant to be one of the better ones in the series but that’s mostly based on the doomed romance and the downbeat ending and I guess that Diana Rigg (The Avengers, 1965-1968) supposedly brought more acting kudos than others in the female lead category. Adopting something close to her Avengers persona would have been more interesting but I guess she was fighting against being typecast.

If you get bored during the endless heraldry nonsense, you can cast your eye over the assortment of Bond girls who include Virginia North (The Long Duel, 1967), Angela Scoular (The Adventurers, 1970), Joanna Lumley (Absolutely Fabulous, 1992-2012), Catherine Schell (Moon Zero Two, 1969), Julie Ege (Creatures the World Forgot, 1971), Anouska Hempel (Black Snake, 1973) and Jenny Hanley (Scars of Dracula, 1970), who, as graduates from this particular talent school, made a greater impact in entertainment than many of their predecessors.

Second unit director Peter Hunt made his full directorial debut but focussed more on his speciality – action – than the drama. Written by series regular Richard Maibaum (Dr No, 1962) and Simon Raven (Unman, Wittering and Zigo, 1971) and more faithful than usual to the Ian Fleming source novel.

Top marks for the action, less so for the rest.