Charlton Heston was as hot as they come. He was coming off what would prove one of the biggest pictures of all time – and tucked away an Oscar as well – with Ben-Hur (1959) and followed it up with another hit El Cid (1961). He had no shortage of offers. He had pulled out of The Comancheros (1961), part of proposed three-picture deal with Twentieth Century Fox but with an unknown director rather than veteran Michael Curtiz who later helmed it with John Wayne. He had turned down Let’s Make Love (1960) with Marilyn Monroe and a remake of Beau Geste to co-star Dean Martin and Tony Curtis.

He entered into discussions with Nicholas Ray to film the bestseller The Tribe That Lost Its Head (never made) and The Road of the Snail (never made), rejected William the Conqueror (never made) and Cromwell (1970). He was turned down in turn by Otto Preminger for Advise and Consent (1961). “Zanuck’s man called from Paris,” he notes, “they have a new role for me in The Longest Day (1962).” That was another false lead.

In due course he signed up for Easter Dinner for producer Melville Shavelson (Cast a Giant Shadow, 1966) released as The Pigeon That Took Rome (1962). By this point he was being pursued by Samuel Bronston. “I had no idea how determined Sam was to have me follow El Cid with another film for him.” Bronston eventually got his wish. “No sooner had I turned down The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) than they shoved it back a year on their schedule and began work on 55 Days at Peking (1963), converting the enormous and half-built set representing Rome into an equally enormous and even more beautiful set representing Peking.”

But that meant delay while the massive Bronston machine kicked into gear. In the meatime Heston was “attracted a bit by the opening pages” of Diamond Head with Columbia. “A good part in an overwritten and melodramatic script,” he observed, concluding, “If it’s treated with great care, it might work out all right.”

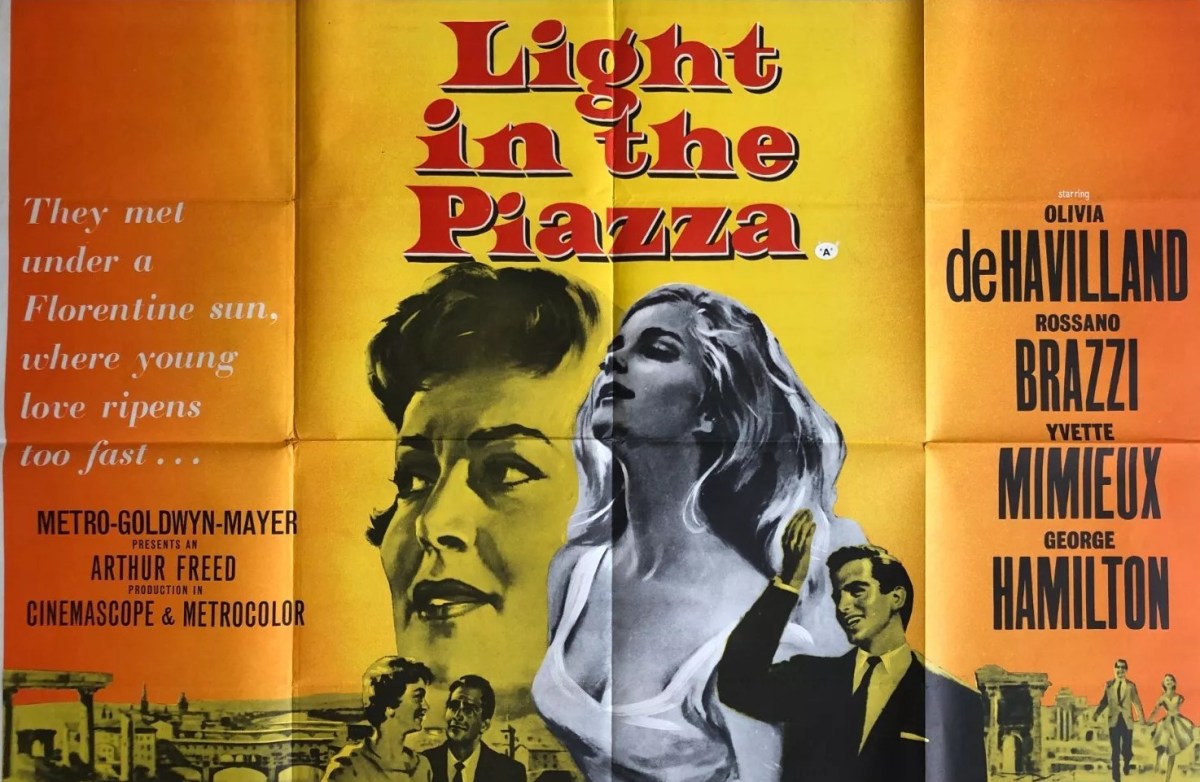

The project moved along apace. A couple of weeks after receiving the script in December 1961, he was in London meeting director Guy Green (Light in the Piazza, 1962) and producer Jerry Bresler, “an amiable man” though Sam Peckinpah might beg to differ after his experiences on Major Dundee, 1965. “He seems a very intelligent fellow,” Green observed, but queried, “how could a man refer with pride to the fact he had made a film called Gidget Goes Hawaiian?”

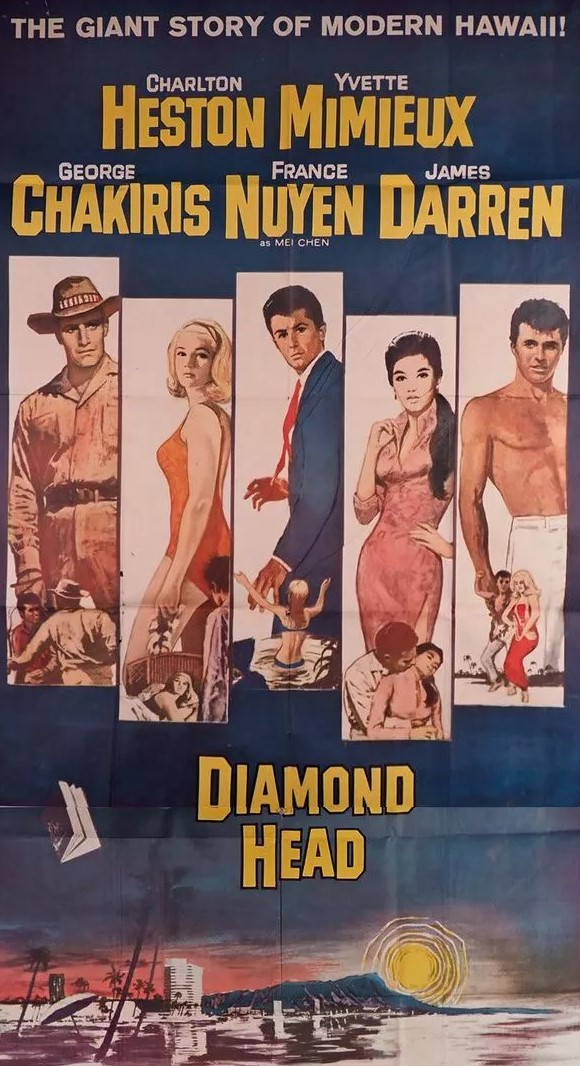

George Chakiris (hot after West Side Story, 1961) was already fixed as second male lead and Yvette Mimieux (Light in the Piazza) was being chased for female lead. She wasn’t available but Heston wasn’t keen on second choice Carroll Baker. Luckily, it turned out Mimieux could do the picture. “On the basis of what we saw in Light in the Piazza, she’s ideal for the part.”

But Heston reckoned the script needed work. He was also disgruntled with the costumes for Diamond Head, complaining, “Why is it designers like to costumes instead of clothes? It’s a grievous fault in a period film, but there’s no excuse in a modern story.”

By March, a few months after committing to the picture, he was out in Hawaii, on the island of Kauai, though the trip itself was not without incident, Heston “sick enough to call a doctor.” They were met with unseasonal rain. They were assured this was very unusual. But it wasn’t. In consequence, the first day’s filming was scrapped, filling the actor with the conviction “the whole project was doomed.” It was another three days before filming commenced – the shoot was plagued with rain.

While Heston was impressed enough with the director (“Guy Green works carefully and thoughtfully”) he was distracted by the lighting.

“Those brutes and reflectors loom larger in my mind…One of the banes of my career has been acting in exterior locations with arc lights and reflectors focused in my eyes, which are very light sensitive. (Dark-eyed actors have an unfair advantage, I’ve always felt.) Most people have no idea of the dimensions of this problem. They always ask you how you can remember the lines…they should wonder instead how you can concentrate on the scene when your every nerve is straining simply to keep your eyes open.” Negotiation with the cinematographer ameliorated the situation.

Similarly, Heston found the director responsive to his concerns. For a key scene with Mimieux, he believed “we can both do better” and taking this on board the director agreed on a reshoot the next day. “I have to project Howland’s need to be loved, though he conceals it. You can’t play this, of course, but it has to be in the scene, in the whole film, if we’re going to bring it off.”

As well as a multitude of media – Hawaii at this stage still a rare location, public interest boosted by the publication of James Michener’s Hawaii in 1958, and to a lesser extent, Diamond Head, a more modest bestseller. Swelling the ranks of visitors to the set was John Ford, obliquely sounding Heston out for an unspecified film, possibly Young Cassidy (1965).

Another issue proved to be the horse-riding. While Heston was an accomplished rider, others were not. “Anxious horse-riding…makes for anxious acting.” Even so, Heston found his mount “harder to handle than I figured.”

Heston’s last day of work was May 18. “I waited round most of the day to do one piddling shot from the dream. No dialog, just my face looming up out of the fog. It’s hard to tell what I think now except that I’m still high on Green. He may have made a film that rises above the melodramatic qualities of the script. He didn’t push me as hard as I should be pushed, but he gave me a lot all the same.”

It was October before Heston viewed the completed picture. His verdict: “Diamond Head looks very slick, smooth, not terribly real, and as though there might be some money in it.” Ever the critic, he added, “I have acted better.”

I’ve mentioned in other Blogs the part played by foreign markets in a star’s appeal – Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson both owed their breakthroughs to foreign box office. Turns out that Heston was in the same league, though an established name when first discovering the size of his fan club abroad.

“My films did invariably well in the Far East and throughout Southeast Asia. Films that flopped elsewhere did fairly well, those that were hits elsewhere did incredibly. The fact that this pattern has continued unchanged accounts in no small degree for my continued viability in films.” Apparently, this was because he represented the Confucius virtues of responsibility , justice, courage and moderation. As if to emphasize his overseas appeal, Diamond Head opened first in Japan, in December 1962.

SOURCES: Charlton Heston, The Actor’s Life, Journals 1956-1978 (Penguin, 1980).