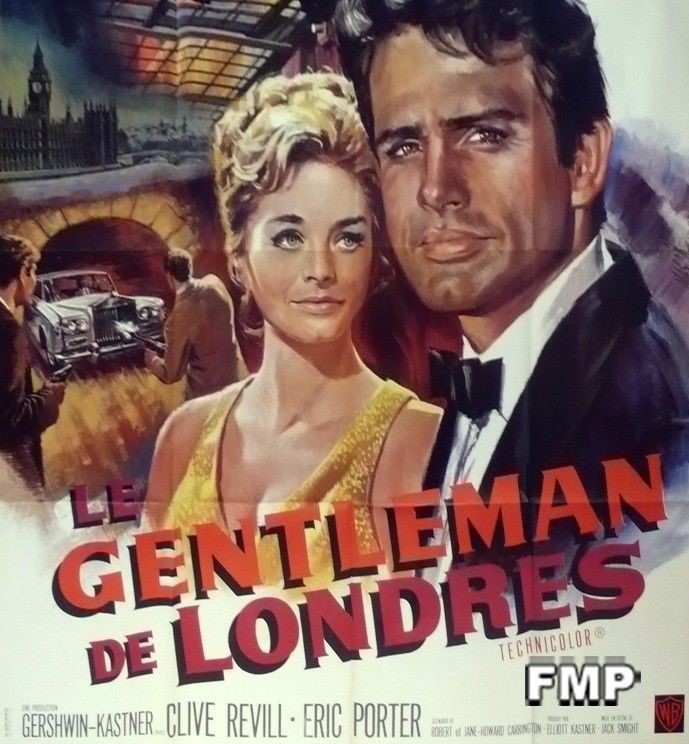

You wouldn’t figure director Henry Hathaway for a caper movie. He seemed more at home with action, whether that be war (The Desert Fox, 1951), adventure (Legend of the Lost, 1957) or western (Nevada Smith, 1966) although he was a dab hand at film noir (Kiss of Death, 1947). And before the big-budget all-star Oceans 11 entered the equation in the same year as Seven Thieves – and stole much of its thunder – the heist movie ran mostly on B-movie steam such as Rififi (1955), The Killing (1956) and Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958).

And probably judged against other glossy efforts of the 1960s like Topkapi (1964) and Gambit (1967) Seven Thieves would appear on the surface to come up a bit short. No doubt accounting for it being so under-rated. But while this is in itself a neat little thriller the kick comes in the emotional entanglements and a succession of twists at the end that sends it in my book into a higher category.

And it’s so outrageously clever that the mystery of why French-based criminal mastermind Theo Wilkins (Edward G. Robinson) would reach out across the Atlantic Ocean to recruit former jailbird Paul Mason (Rod Steiger) to spearhead the heist of a cool four million dollars from a Monte Carlo casino is not resolved until the end, and in spectacular fashion.

Technically, there are actually only six thieves, the other is an inside man, Raymond (Alexander Scourby), who has fallen for the seductive charms of nightclub dancer Melanie (Joan Collins). Making up the rest of the septet are safe cracker Louis (Michael Dante) and muscle-cum-driver Hugo (Berry Kroeger) with Poncho (Eli Wallach) playing the key role of the pretend crippled, arrogant, irascible millionaire – and contrary to the claims of one poster he is the decoy not Melanie.

Distrust of his team makes Theo bring in Paul, who ruthlessly knocks them into shape, putting into seamless action the plan devised by Theo. Simply put, Poncho is going to act as a distraction by having a heart attack at the gambling table while Paul and Louis climb out a window along a ledge to the casino director’s flat which provides, by means of an elevator, direct access to the underground vaults. Once they’ve stolen the cash, they clamber back along the ledge and hide in the flat where, by this time, Theo, playing the role of Poncho’s personal physician, has taken him. The money will be hidden in Poncho’s wheelchair and removed to a waiting ambulance.

But Paul is a rather suspicious character and wants to know what he’s letting himself in for so in turn works out the weaknesses of his team. Melanie hides behind a façade of high birth, Pancho is too reckless, “measuring danger only in terms of profit,” Hugo prone to unnecessary violence, while Louis has omitted to mention he is terrified of heights, the ledge on which the operation depends standing on a 100ft high cliff.

vs Little Caesar (Robinson).

The plan relies on Poncho actually appearing to be dead, so dead that the casino director (Sebastian Cabot) will not hesitate, at Theo’s insistence, to shift him out of sight of the rest of the gamblers into his flat. But Complication No 1 is that Poncho doesn’t want to be dead, even if it is a ruse, skeptical of Theo’s plan to convincingly knock him out by means of a carefully measured dose of cyanide. Complication No 2 is that a night club client recognizes Melanie and casts doubt on her credentials as a lady of quality. Complication No 3 is that English physician Dr Halsey (Alan Caillou) questions whether Poncho is as dead as he seems.

But such complications are nothing compared an extraordinary range of twists that raise tension sky-high at the movie’s denouement. I challenge you to guess what these three superbly-conceived twists would be, all of them one by one turning the project on its head, and it rapidly shifts from one direction to another, ending with an unbelievable – and yet so in keeping with the premise – climax.

Attention to character detail lifts this out of the rut, whether it be Theo’s penchant for collecting seashells, Paul resplendent in a white suit, Melanie resisting the blandishments of becoming a kept woman, Raymond trying to climb out the murky depths into which the lure of Melanie has taken him, and a series of subtle relationships, some developing through the robbery, others which began long before the heist working themselves out.

The heist itself is well done, tension kept constant mostly through the failings of the crew and the suspicions of the dupes. All in all an excellent picture.

This was a critical film in the careers of most of the cast. Edward G. Robinson (The Cincinnati Kid, 1965) was handed his first top-billed role in four years. It was a deliberate change of pace for Rod Steiger (The Pawnbroker, 1964). For Eli Wallach, best known at the time for stage work, it was the first of three films that year that would launch him into the higher ranks of top supporting stars; it was followed by The Magnificent Seven and The Misfits. After being leading lady to the likes of Gregory Peck and Richard Burton, this spelled the end of Twentieth Century Fox’s belief in Joan Collins’ star qualities while for Michael Dante (The Naked Kiss, 1964) it was a step up.

Wallach and Dante could be accused of over-acting but Robinson, Steiger and Collins all act against type with considerable effect. Hathaway does a superb job working from a script by Sydney Boehm (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967) based on the Max Catto bestseller.