What wouldn’t Hollywood give now for a pair of personable players who could take as slight a piece of fluff as this and through sheer force of screen personality turn it into an enjoyable experience. Based entirely around misconception, misunderstanding, characters at cross purposes and mild business satire this would have been hailed as a classic had it appeared in the golden age of the screwball comedy.

Playboy Tony Ryder (Dean Martin) inherits a publishing empire from his uncle but discovers an unsavoury fact about his relative’s demise that could severely damage the business. A naked woman was seen running from his hotel room. When hotel house detective Lasker (Jack Weston) identifies her as Katie Robbins (Shirley MacLaine), a lowly employee in the company, the suspicious minds of big business surmise that she intends to blackmail them.

The plot, such as it is, concerns Ryder and Co’s attempts to avoid this, by bribing her to shut up and at the same discrediting her. Ryder is conflicted, in part because he fancies her rotten, in part because he doesn’t quite believe she could be so duplicitous, and in part because he can’t afford to risk believing her. For some reason, as a researcher, she is involved in union negotiations, giving him the opportunity to get to know her better, as part of a “sub-committee of two” established to examine union claims more thoroughly.

So it’s basically one set-piece after another. A flashback explains why Katie came to be in the uncle’s bedroom – to escape in the same hotel the lustful attentions of the elderly wealthy guest Kirby Hackett (Johnstone White) whom she saved from drowning. Her behaviour at the uncle’s funeral suggests she is stricken by his death. And unfortunately, she is the recipient from the grateful Hackett of a mink coat worth thousands of dollars which, on her meagre salary, she can’t explain.

Katie is dithering over her planned wedding to dull vet Warren Kingsley Jr. (Cliff Robertson) and, aiming to discredit her with him, Ryder plants the seed that actually she is a showgirl on the side, arranging for her to receive five star treatment at various nightclubs, inciting suspicion from her fiancé and his extremely conventional parents. In order to get to the bottom of everything, Ryder agrees to be bugged for a private meeting with Katie. You can imagine how that goes. But the outcome is never in doubt of course.

What the audience knows but the participants do not is that this couple is well-suited. Ryder is far from the playboy of his reputation, having started at the bottom of a rival publishing empire and worked his way up to the top, so he turns out to be a more astute businessman than the sycophants on the board anticipate – “you may not be much but you’re all we’ve got” typical of the welcome he receives. Far from being a good-time girl, Katie is a woman of principle, refusing to take the mink coat as a gift and determining to pay it off at the rate of $10 a week.

The humour derives almost entirely from the cross-purpose nature of the plot and the set-pieces work out well, especially when Ryder kidnaps a sheepdog as an excuse to visit the vet, and stumped for a reason comes up with the notion the animal is suffering from amnesia. “He gives me that ‘who are you’ look,” Ryder explains. As the tale unfolds Kingsley becomes more insufferable by the minute.

There’s a romantic subplot involving Katie’s outgoing office chum Marge (Norma Crane) and the shy detective and some satirising of big business but that all plays out in relation to the main story.

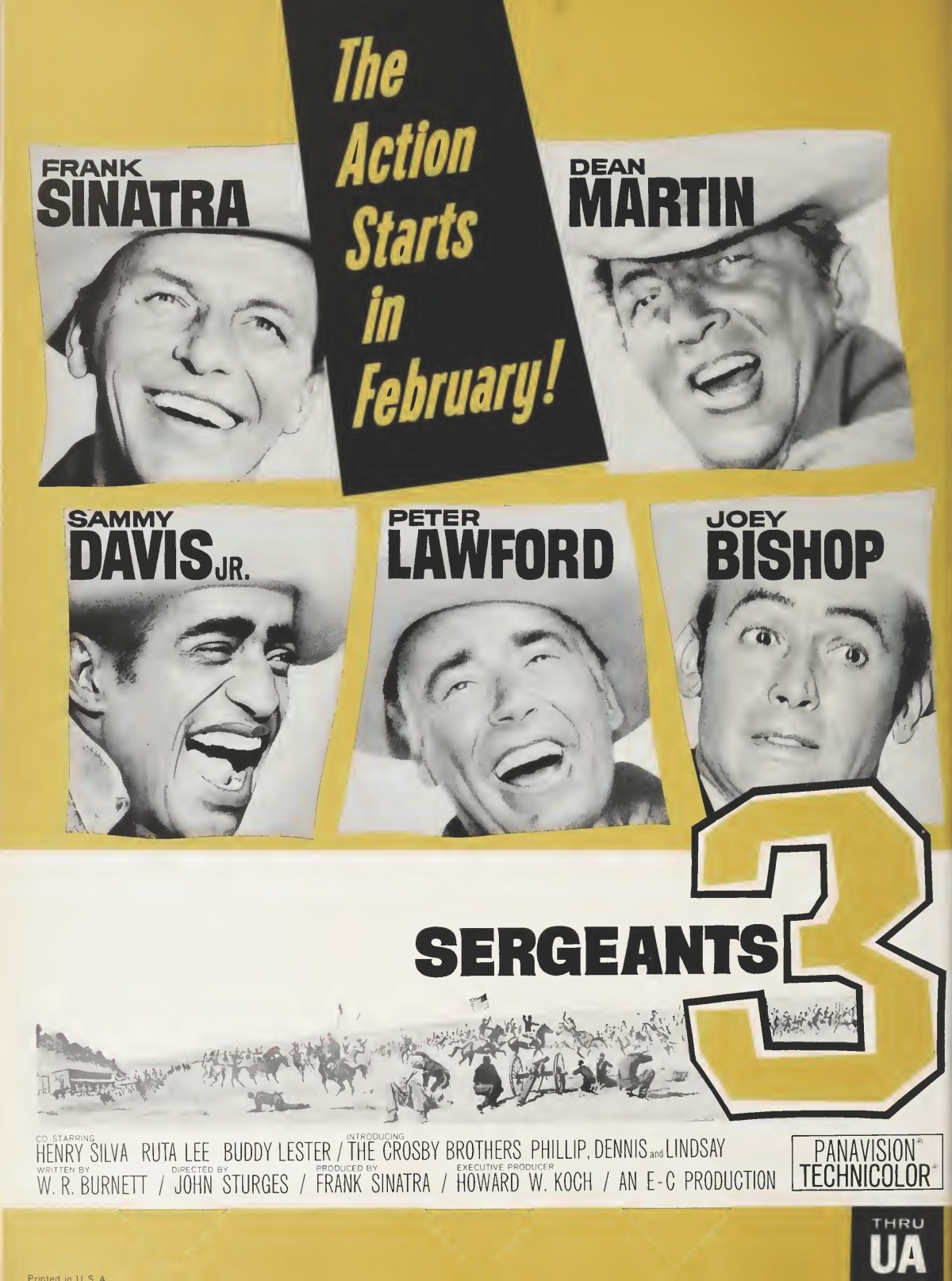

If you remember Dean Martin from heavyweight dramas like The Young Lions (1958), Some Came Running (1958), Rio Bravo (1959) or the breezy Rat Pack comedies and the equally breezy Matt Helm spy pictures will probably not be aware he started his career in comedy, as one half of the Dean Martin-Jerry Lewis combo, a box office sensation in the early to middle 1950s. So, although he was primarily the straight man to the more obviously comedic Lewis, he was still well versed in the nuances of the genre. Nothing is ostensibly played for laughs, but he gets the laughs nonetheless.

Martin was always badly under-rated, in part because of the perma-tan, in part down to the his television show, and in part because he just wasn’t Frank Sinatra. But he was an accomplished actor, as this proves. One of the aspects of his performance I liked was that he moves with purpose. In most movies, characters cross a room or change position simply because a director calls the shots. But here, every time Martin moves it’s for a designated reason, to touch something, admire something, maneuver himself closer to someone else.

Shirley MacLaine is also refreshing, considerably less conniving or lovelorn than in her breakthrough role in The Apartment (1960), and coming to believe in her screen presence. She inhabits this character’s innocence very well, is suitably baffled on occasion, and exhibits a screen persona that simply lights up the screen. Together they are a great screen couple and in the charisma-starved Hollywood of today would be very welcome.

Cliff Robertson (The Honey Pot, 1967), almost unrecognizable without that hefty hunk of hair and the grandstanding he often effected, plays his small role to perfection. Norma Crane (Penelope, 1966) and Jack Weston (The Cincinnati Kid, 1965) – minus the screen tics he later exhibited – are quietly effective. Veteran Charles Ruggles (The Parent Trap, 1961) puts in a decent shift.

Confident direction by Joseph Antony (The Rainmaker, 1956) in just his fourth film out of a grant total of five makes you forget this was based on a hit play by Margit Veszi and Owen Elford. The screen transition was down to Maurice Richlin (The Pink Panther, 1963), Edmund Beloin (Donovan’s Reef, 1963) and future bestselling author Sidney Sheldon (Billy Rose’s Jumbo, 1962).

The real beauty of this piece is how effortless it all looks. The characters are grounded and believable, viewed from varying perspectives the plot remains logical, and there is enough daft invention to tickle your fancy.