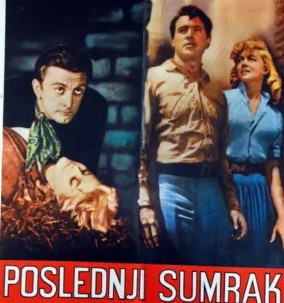

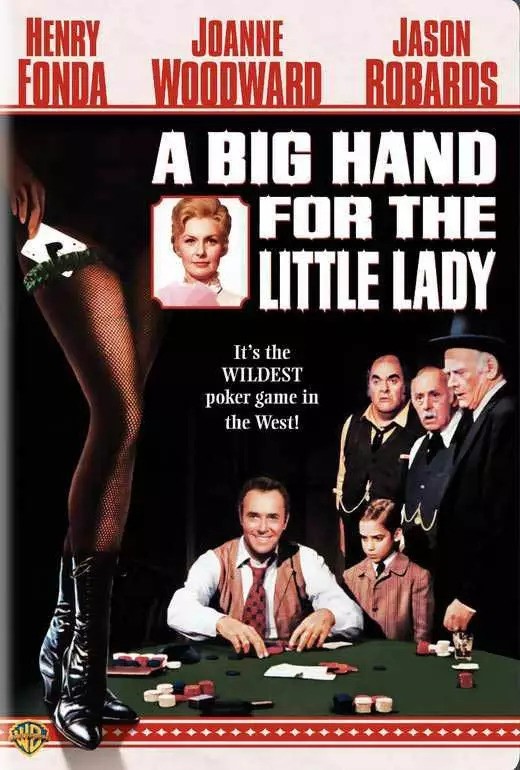

Woefully under-rated western with three A-list stars at the top of their game in a taut drama with an explosive ending. Not surprising it was overlooked at the time with John Wayne duo El Dorado and The War Wagon, Paul Newman as Hombre and an onslaught of spaghetti westerns garnering more attention at the box office. Though a rewarding watch, be warned this is more of a slow-burn drama than a traditional western and both male leads play against type.

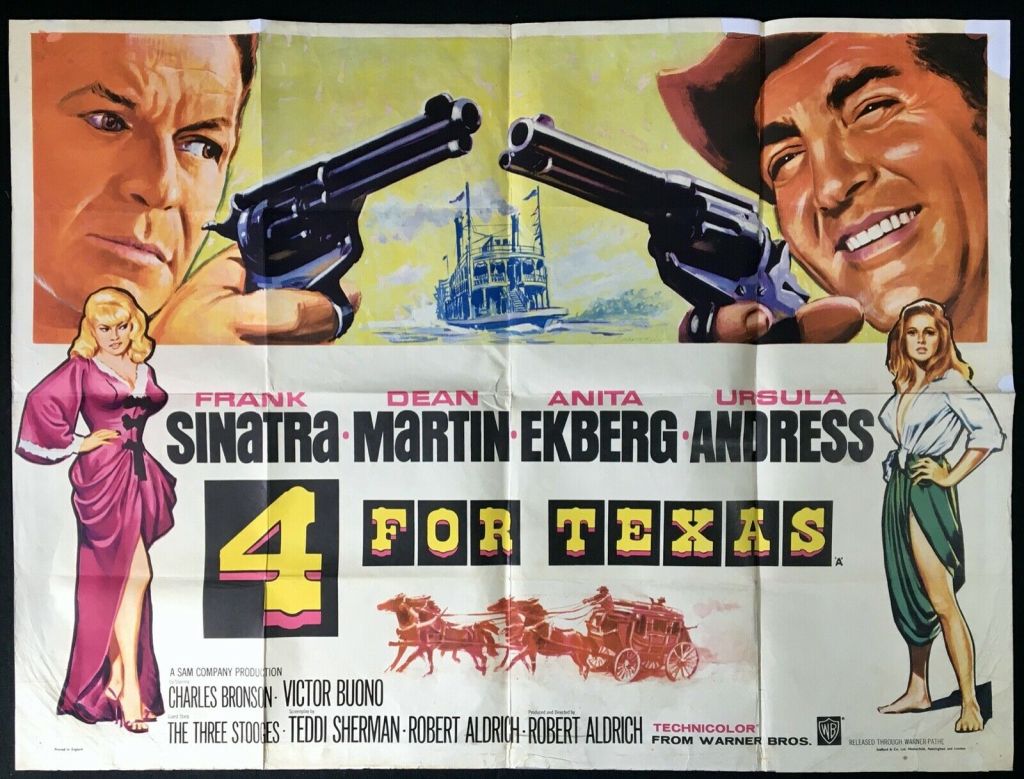

Former lawmen Dolen (George Peppard) and Ben Hickman (John McIntire) have invested in a stagecoach business owned by twice-widowed Molly Lang (Jean Simmons), just about the only business in Jericho in which Alex Flood (Dean Martin) does not have a controlling share. Dolen’s first reaction on surmising Flood’s power is to quit, “stepping in’s a habit I outgrew.” And it’s not a bad approach given that Flood is judge, jury and executioner and apt to leave victims strung up to dissuade dissent.

Dolen and Flood have a great deal in common, moving from ill-paid law enforcement into business, Flood, having cleaned up the town, stayed on to reap the profit. While Dolen avoids confrontation, Molly aims to stir up opposition, invoking ruthless reaction.

What’s unusual about this picture is it’s mostly a duel of minds, Dolen and Flood sounding each other out, neither backing down even while Dolen intends quitting and when he happens to win a bundle on a poker game with Flood you have the notion that was somehow an inducement to help him on his way. It’s a power game of sorts, too, between Dolen and Molly, she determined to give no quarter to the point of drinking him under the table.

But when violence occurs it is absolutely brutal, Flood’s knuckles bloodied raw as he batters a man foolish enough to challenge his rule of law, Dolen taking an almighty whipping from Yarbrough (Slim Pickens), Molly viciously slapped around by Flood for daring to look at Dolen. When Dolen does move into action it is with strategic skill, gradually reducing the odds before the inevitable shoot-out between respectable citizens and gangsters.

A good half-century before the notion took hold, this is a movie as much about entitlement, about those doing the hard work receiving just reward, Flood, having risked his life to tame the town, deciding he should be paid more than a sheriff’s monthly salary. And the western at this point in Hollywood development had precious few female businesswomen in the vein of Molly.

Both Dean Martin and George Peppard play against type. An unexpected box office big hitter through the light-hearted Matt Helm series, Martin explodes his screen persona as this vicious thug, town in his thrall, contemptuous of his victims, turning politics to his advantage, but still happy to hand out a beating when charm and chicanery fail. This is one superb, and brave, performance.

For Peppard, this picture is the bridge between the brash persona of The Blue Max (1966) and Tobruk (1967) and the thoughtful introspective characters he brought to life in P.J. / New Face in Hell (1968) and Pendulum (1969). Perhaps the most telling difference is a little acting trick. His blue eyes are unseen most of the time, hidden under the shade of his wide-brimmed hat. He is not laid-back in the modern sense but definitely unwilling to plunge into action, movement both confined and defined, a man who knows his limits and, no longer paid to risk his life, unwilling to do so.

Jean Simmons (Divorce American Style, 1967) is in excellent form, neither the feisty nor submissive woman of so many westerns, but clever and determined, perhaps setting the tone for later female figures like Claudia Cardinale in Once Upon a Time in the West (1969) and Raquel Welch in 100 Rifles (1969).

And this is aw-shucks Slim Pickens (Major Dundee, 1965) as you’ve never seen him before. John McIntire had spent most of the decade in Wagon Train but he punches above his weight as a mentoring lawman. If you are trying to spot any other unusual figures keep an eye out for legendary Variety columnist Army Archerd who has a walk-on part as a waitperson.

More at home in television, director Arnold Laven took to the big screen on rare occasions, only twice previously during the decade for Geronimo (1965) and The Glory Guys (1965), but here he handles story and character with immense confidence and considerable aplomb. The direction is often bold – major incidents occur off screen so he can concentrate on the reactions of the main characters. There is a fabulous drunk scene, one of the best ever – plus an equally good hangover sequence. The violence is coruscating, all the more so because it is not delivered by gun.

There’s a great screenplay by Sidney Boehm (Shock Treatment, 1964) and Marvin H. Albert (Duel at Diablo, 1966) which swings between confrontation and subliminal menace.

This would have been Peppard’s picture, given he was demonstrating under-used acting skills, but he’s been to the draw by even better performances by Dean Martin as you’ve never seen him before and Jean Simmons.

A cracker.