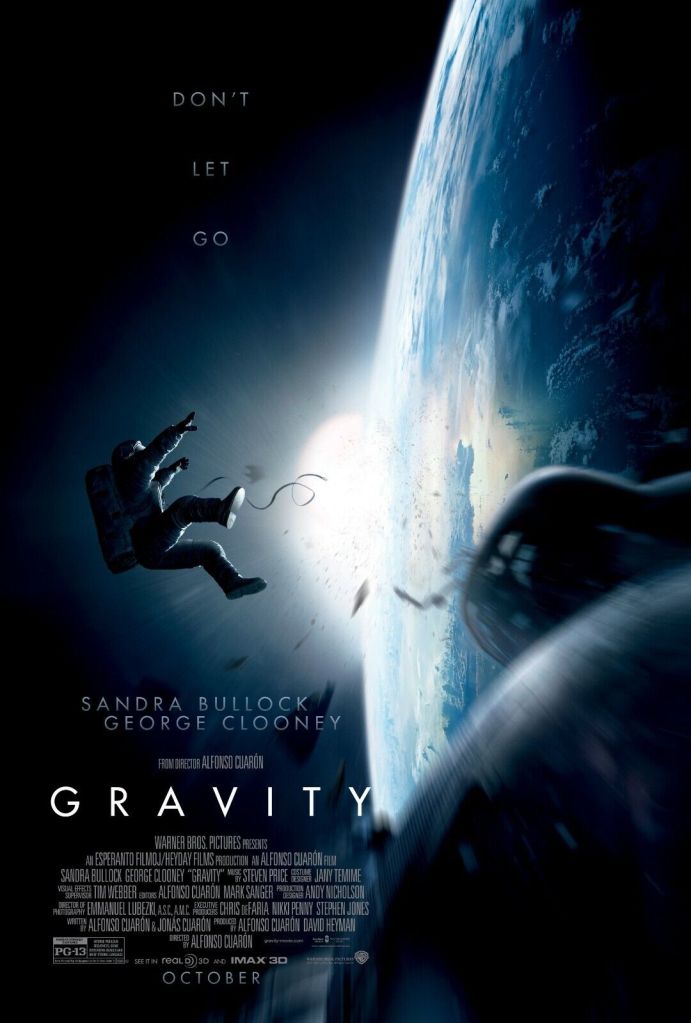

Superb piece of counter-programming saw this sleek sci-fi disaster picture pitted against the uber-lengthy Killers of the Flower Moon. Clocking in at under half the running time of the Scorsese feature (but with the bonus of 3D), almost B-movie style in a mean 93 minutes, it still stands as an awesome achievement by Oscar-winning director Alfonso Cuaron (Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, 2004).

Stripping away the tedious back story that generally afflicts sci fi, and bold enough Psycho-style to dispense with a major box office figure halfway through, like John Wick it’s action from the get-go. No aliens here, just a couple of almost nerdy astronauts, sewn-up grieving mother Ryan (Sandra Bullock) and jabber mouth Matt (George Clooney), doing boring maintenance on a pretty mediocre-looking space vehicle, not the kind that’s going to blast off into deep space mapping unknown territories.

Russian space trouble causes a chain reaction that sends hundreds of miniature missiles in diabolic orbit around Earth, hitting the beleaguered Yanks time and again until their entire crew, and that of Russian and Chinese space units, is wiped out. Fits into the survival-in-space mini genre that accommodates Apollo 13 (1995) as easily as The Martian (2105) and the sub-sub-genre of women-surviving- in-space that Sigourney Weaver kicked off in Alien (1979).

So, you know from the off that you’re not going to get a woman bleating about the situation and unable to cope. It’s all about hanging on and using whatever skills got humanity into space in the first to get them back out. As usual, the answer is a pretty straightforward piece of reverse engineering.

But mostly this is sheer spectacle held together by one of the greatest actors of modern times in Sandra Bullock (The Lost City, 2022). When you need someone to emote for the most part from under a space suit, she’s the one. Takes the feet from under you though in the human twist. Why not just let nature take its course, instead of fighting for your life? Might have made a bigger psychological impact if Ryan had just let go, but that’s not, I would imagine, as big box office as the battle for individual survival, especially from someone who has zilch to live for.

I’ve no idea how they achieved the effects and don’t want to know, but a lot of it looks as if shot in-camera, with Ryan floating around in the spaceship. Quite how Cuaron, on triple-hyphenate duties here, writer-producer-director, captured her helplessly turning cartwheels across empty space is anybody’s guess.

If it had been the usual muscled-up candidates hurtling towards their doom, I doubt if audiences would have cared so much, but the everywoman aspects of Ryan nailed it. No point trying to explain the narrative of destruction, suffice to say that whatever deadly comes her way is just as mundane as whatever is helpful.

Pure raw cinematic ride with no let-up in the action. Not sure it will hold up so well on a small screen (though the Blu Ray should provide a hefty impact) so I’m grateful for Warner Brothers for bringing this back for a reissue one-night stand to celebrate its tenth anniversary. Not sure either that it found much of an appreciative audience though. There was just me and one other person in the cinema audience last night.

A blast with heart.