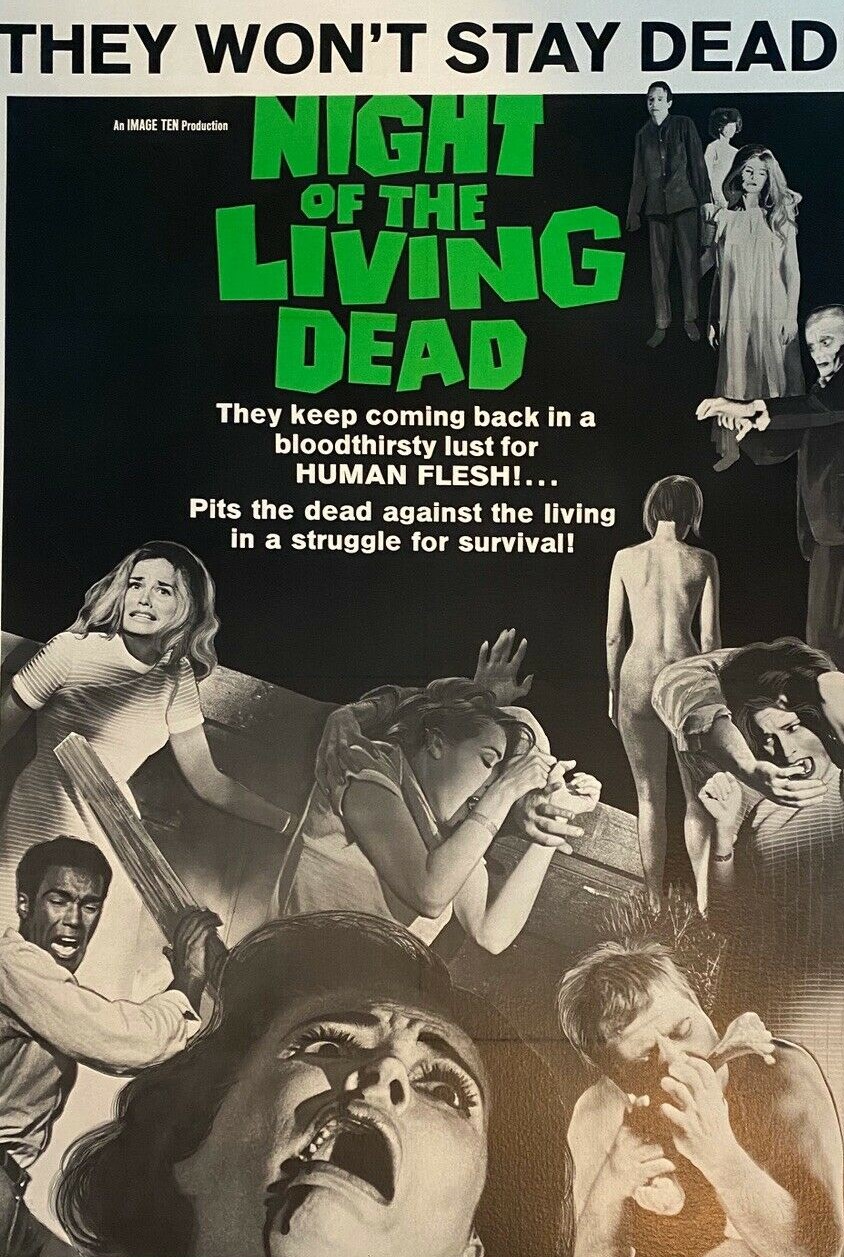

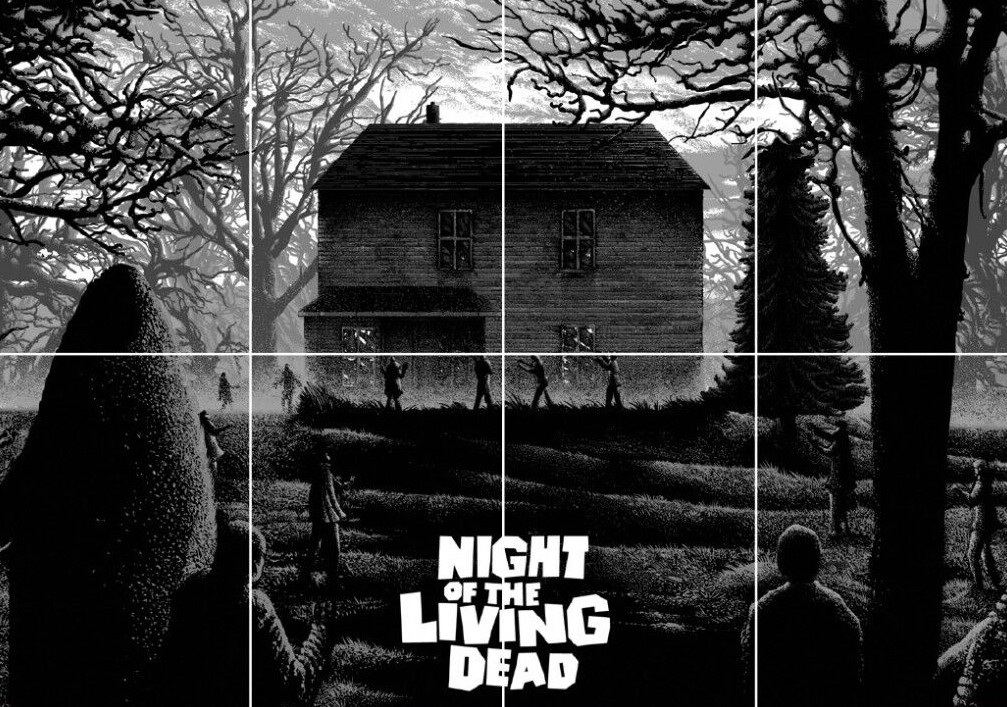

Ground-breaking thriller in the apocalyptic vein that appeared destined for oblivion after being judged too over-the-top by the AIP/Hammer criteria suitable only for the denizens of late-night horror quintuple bills. I say “thriller” because even by today’s slaughter-fest standards when the heroes/heroines generally escape, it was unheard-of for the entire cast to die, especially considering the post-ironic ending which made a sharp political point.

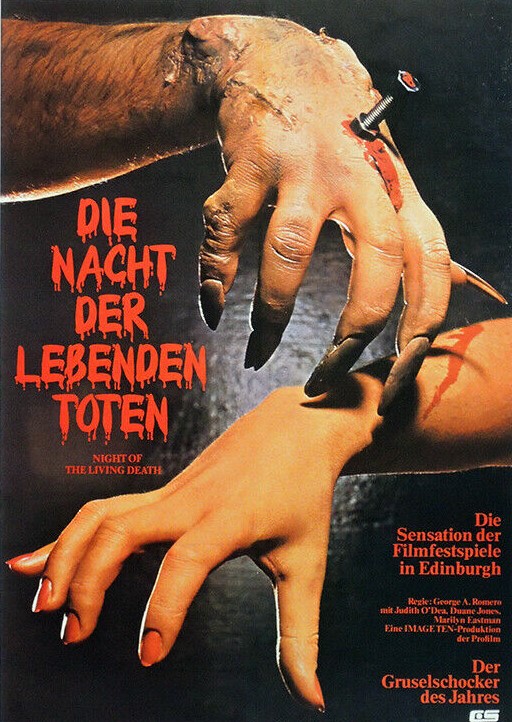

Brother and sister Johnny (Russell Streiner) and Barbara (Judith O’Dea), having driven 200 miles to visit their father’s grave, are ambushed in a cemetery by a zombie. Johnny is chalked up as victim number one. Barbara escapes to what appears to be an abandoned house, attacked by more zombies, where in a by-now near-catatonic state she is eventually joined by the more action-oriented Ben (Duane Jones) who boards up door and windows and fires at the ghouls with a rifle.

Hiding in the cellar are the Coopers, Harry (Karl Hardman) wife Helen (Marilyn Eastman) and daughter Karen (Kyra Schon), ill from being bitten by the monsters after their car was overturned, and Tom (Keith Wayne) and girlfriend Judy (Judith Ridley). In the ensuing panic and continued onslaught, the numbers of zombies growing by the minute, Harry determined they would be better off hiding in the cellar and at one point locks Ben out of the house.

Radio and television broadcasts reveal a mass outbreak of people rising from the dead and feasting on the living, the result it appears of radiation in space, caused by man-made accident. The zombies can be killed off by a bullet or blow to the head or being burned. A gas pump being nearby, Ben, Tom and Judy drive there but while Ben lays down a carpet of fire to deter the marauders Tom accidentally spills gas over the truck which catches fire. Ben escapes but the couple are incinerated, turned into a tasty barbecue for the invaders.

While the relentless siege continues, Karen dies and is reanimated. And so, as you don’t expect, there is no escape, the survivors fighting zombies outside and the living dead inside.

The final image, a photographic montage, takes the movie in another direction, down the Civil Rights route, as the corpse of the only African American is hoisted up on meat hooks.

Until George A. Romero (Dawn of the Dead, 1978) took this idea and ran with it, the indie-scene was populated by cheaply-made movies of no discernible artistic credit aimed at the bottom end of the distribution market or by artistically-minded directors who hoped their talents might be acclaimed and lead to a fat Hollywood contract.

Although there was no shortage of shockers, most had laughable special effects, little in the way of narrative, and certainly no earth-shattering concept like nobody gets out of here alive.

A budget of just over $100,000 ensured there was little room for grandiose special effects but nonetheless the scenes of relentless zombies striding forward, the single creature at the outset joined by a mass, was cinematic genius. Nor were these fragile ethereal beings, but strong enough to physically kill and turn over cars. On top of that was the revelation that death did not sate their hunger, and they weren’t vampirically-inclined either, the tastes lying in the cannibalistic. If you were able to die quickly enough to be reanimated you might escape being turned into a meal.

Taboo-busting came easily. Never mind flesh-eating zombies, and graphic violence, what about matricide? And perhaps a nod towards the power of relentless pressure, the armies of the night here could easily translate to the armies of protesters taking to the streets in broad daylight to march against injustice and Vietnam, whose continued opposition to government would drive change.

No doubt the decision to film in black-and-white was budget-driven, but that turned out to be a boon, no need to invest in gallons of what might pass as red blood, or create bloody corpses, just focus on the relentless threat.

It helped, too, that the characters under siege were very human, Barbara going out of her head with fear, isolationist Harry willing to kill the others to defend his notion of hiding out in the cellar, hoping to escape unscathed.

This was the ultimate word-of-mouth picture, critically dismissed not to say reviled on initial release, but gradually picking up an audience until it became a must-see movie. Romero’s horror approach became widely imitated, though his influence took years to permeate down. Co-writer John A. Russo later became a director, helming Santa Claws (1996).