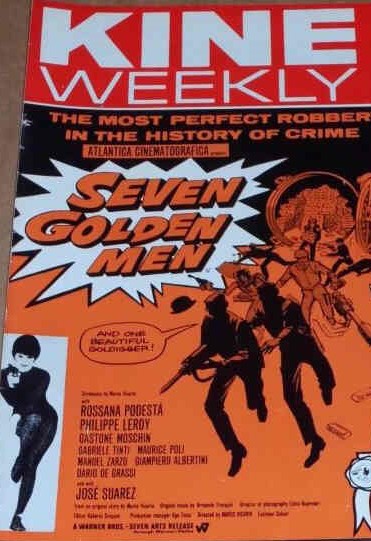

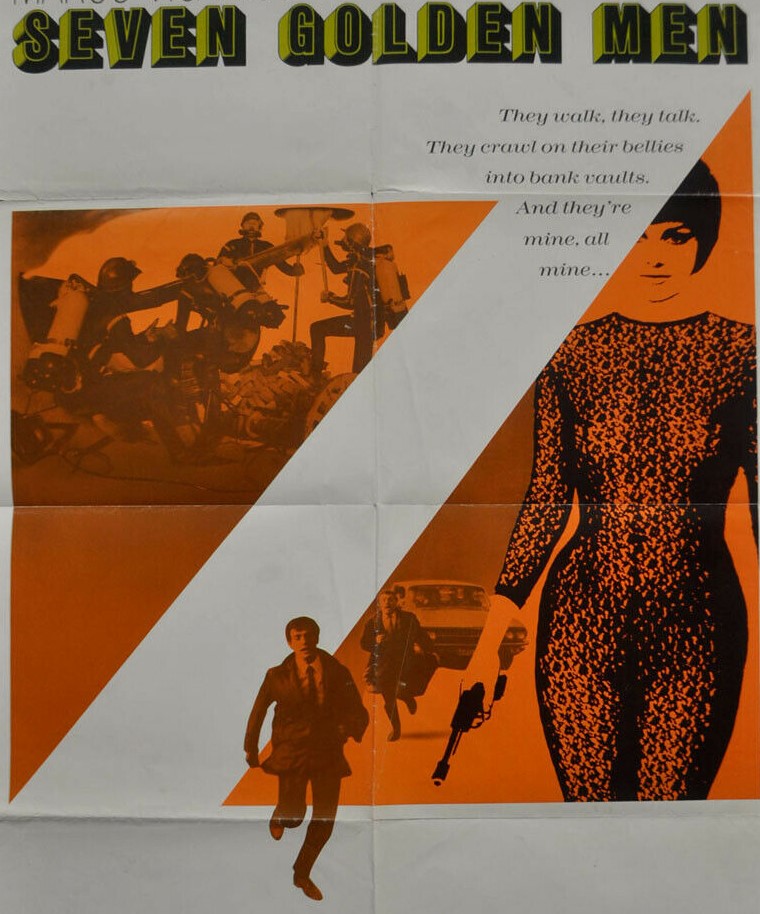

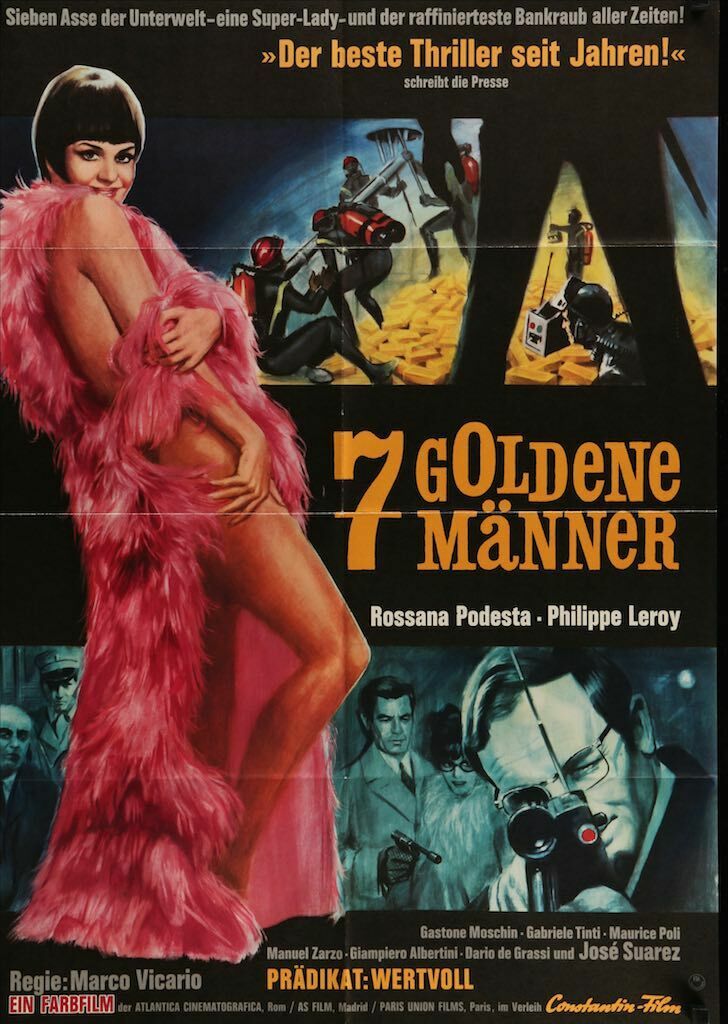

Very stylish caper picture that dispenses with the recruitment section, the ingenious hi-tech robbery accounting for the first half, escape and double-cross the second, a slinky Rosanna Podesta an added attraction/distraction. The Professor (Phillippe Leroy), in bowler hat and umbrella, orchestrates the gold bullion theft from an uber-secure bank using hidden microphones and cameras and a host of electronic equipment, the inch-perfect heist organized to mathematical perfection and timed to the second.

His team, disguised as manual workers, dig under the road, don scuba gear to negotiate a sewer, drill up into the gigantic vault and then suck out the gold bars using travelators and hoists. Giorgia (Podesta), sometimes wearing cat-shaped spectacles, a body stocking and other times not very much, causes the necessary diversions and plants a homing device in a safety deposit box adjacent to the vault. Occasionally her attractiveness causes problems, priests in the neighboring block complaining she is putting too much on show.

It’s not all plain sailing. A cop complains about the workmen working during the sacrosanct siesta, a bureaucrat insists on paperwork, a radio ham picks up communication suggesting a robbery in progress, the police appear on the point of sabotaging the plan.

But the whole thing is brilliantly done, the calm professor congratulating himself on his brilliance, Giorgia seduction on legs. The getaway is superbly handled, the loot smuggled out in exemplary fashion, its destination designed to confuse. Then it is double-cross, triple-cross and whatever-cross comes after that, with every reversal no idea what is going to happen next. It is twist after twist after twist. Some of the criminals are slick and some are dumb. As well as the high drama there are moments of exquisite comedy.

Italian writer-director Mario Vicario (The Naked Hours, 1964) handles this European co-production with considerable verve and although, minus the normal recruitment section, we don’t get to know the team very well except for the professor and Giorgia, each is still given some little identity marker and in any case by the time they come to split the proceeds we are already hooked.

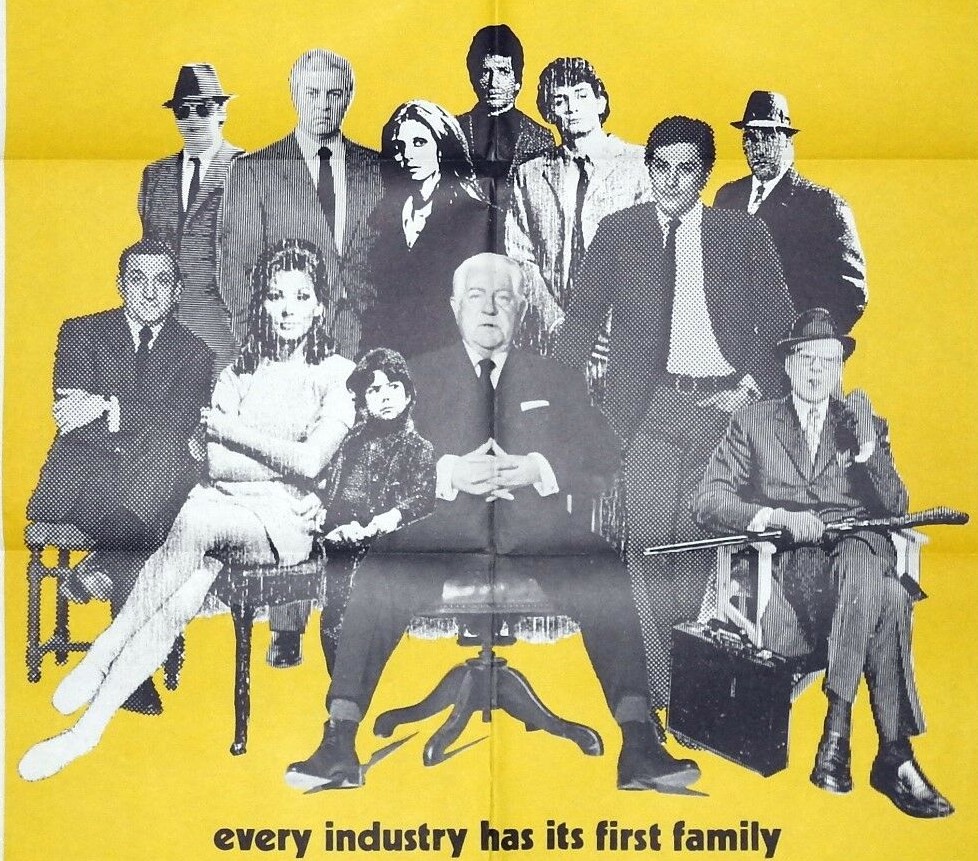

Frenchman Phillippe Leroy (Castle of the Living Dead, 1964) is the standout as a mastermind in the British mold, stickler for accuracy, calm under pressure, working with military precision. Podesta (also The Naked Hours) has no problem catching the camera’s attention or playing with the emotions of the gang to fulfill her own agenda. The gang is multi-national – German, French, Italian, Spanish Portuguese, Irish – with only Gabriel Tinti likely to be recognized by modern audiences.

And there is a terrific score by Armando Trovajoli (Marriage Italian Style, 1964) that changes mood instantly scene by scene. One minute it is hip and cool jazz, the next jaunty, and then tense.

Worth a watch.