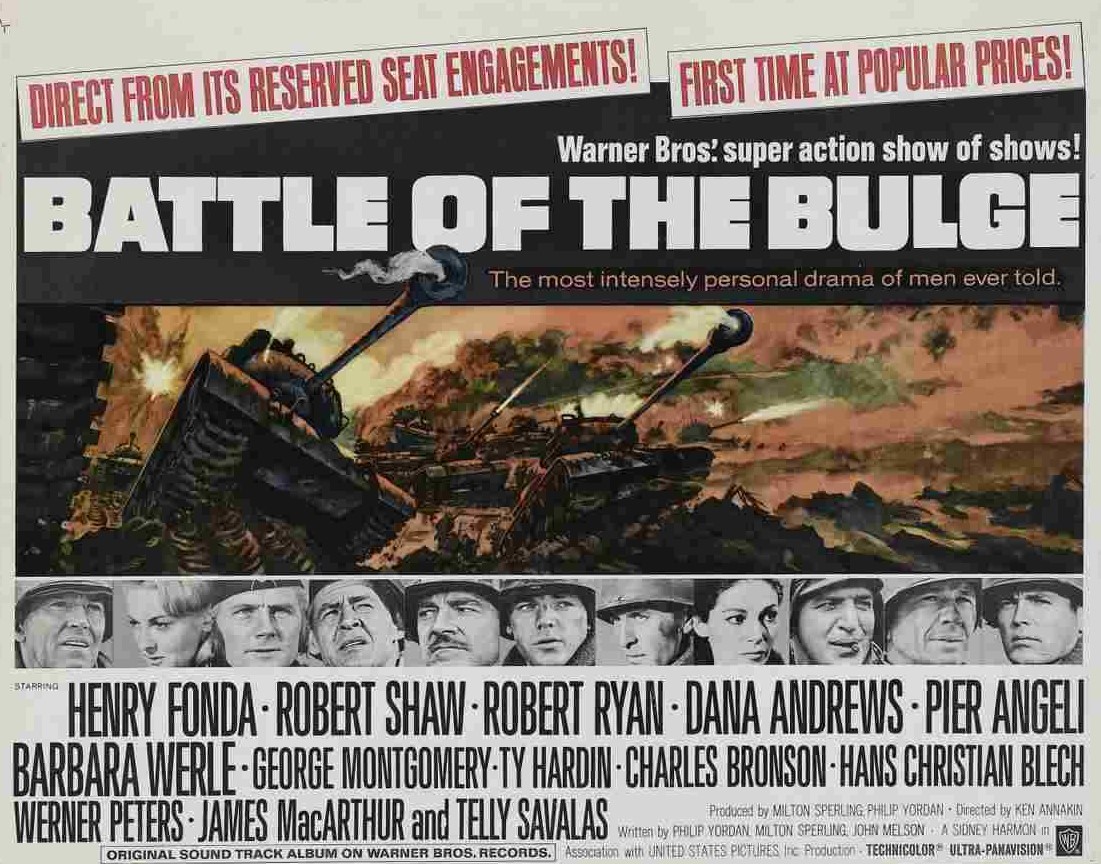

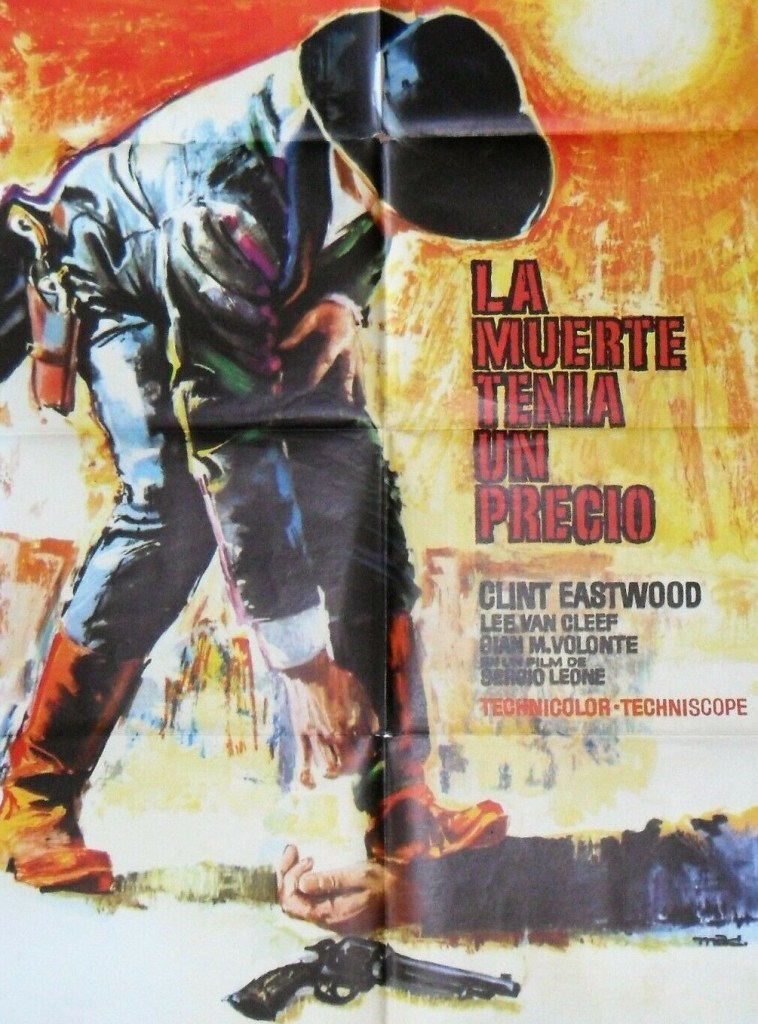

The prospective casting was tantalizing. How about Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin, a pairing for the ages, two of the toughest guys in screen history? Failing that, Eastwood and Charles Bronson, The Man With No Name vs The Monosyllabic Man? The role of Colonel Mortimer could also have gone to Henry Fonda or Robert Ryan before in one of the movie business’s oddest tales it ended up with Lee Van Cleef.

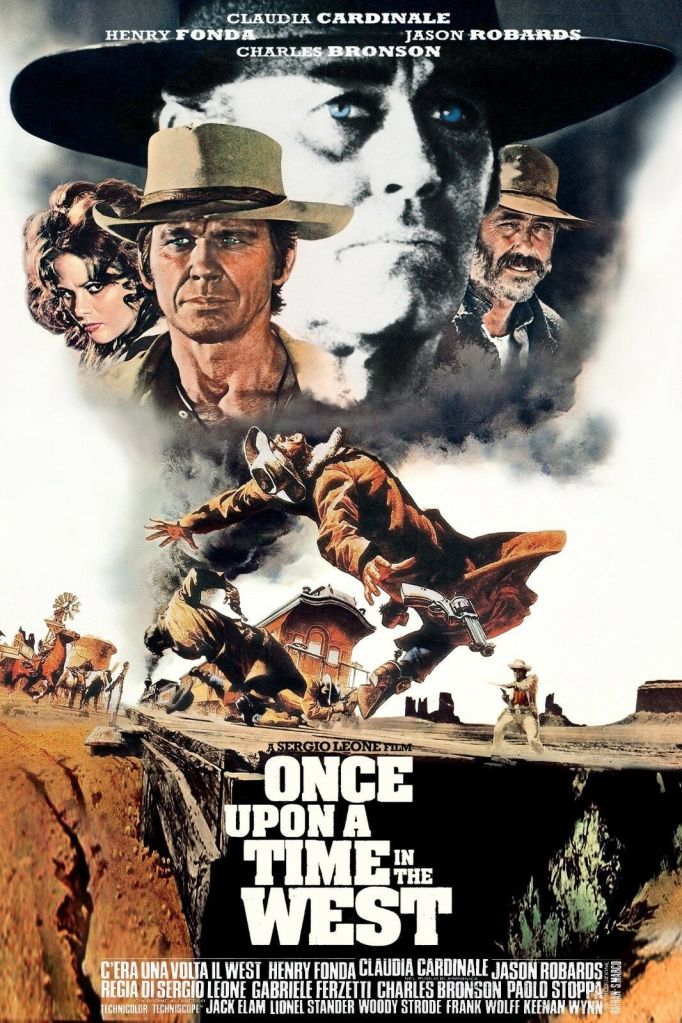

In due course Bronson and Fonda would work with Sergio Leone in the director’s best film, Once Upon a Time in the West (1969). Fonda’s agent had already dodged Leone’s entreaties once, having rejected A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Marvin was, in fact, all set, an oral agreement in place until a few days before shooting began on For a Few Dollars More he suddenly opted instead for Cat Ballou (1965), a decision that won him an Oscar and turned him into an unlikely star.

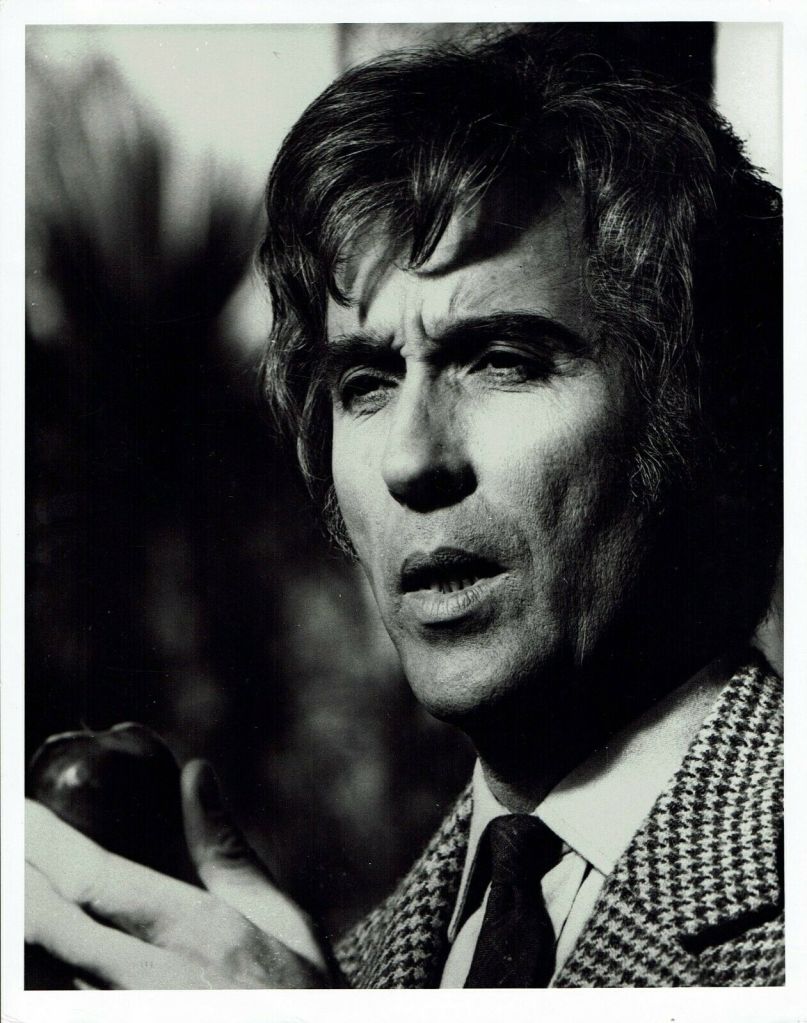

When none of his first choices proved available or interested, Leone turned to Van Cleef. Or, more correctly, a photo of the actor pulled from an old casting catalog. Although a western buff like Leone remembered Van Cleef from his debut in High Noon (1952) plus Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), The Tin Star (1957) and a dozen other bit parts and supporting roles in westerns, Van Cleef had not been credited in a movie since The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

He proved virtually impossible to track down. No small surprise there because he earned a living mostly as a painter now, a car accident having left him with a limp. He couldn’t run, much less ride anything but a docile horse. He required a stepladder to get mounted. Leone flew to Los Angeles and his first sight of Van Cleef, older than his photograph, proved his instincts correct, Van Cleef’s face “so strong, so powerful.” The salary on offer, for a down-on-his-luck actor scarcely able to pay a phone bill, was a fat purse of $10,000. (Eastwood’s salary was $50,000 plus a profit share compared to just $15,000 for the first film).

Leone put him to work right away, the day he arrived in Italy filming reaction shots. It was just as well his input that day was so simple because, as Clint Eastwood had discovered, the language barrier was a problem. Equally disconcerting was that Van Cleef had no idea why he had been chosen, and since A Fistful of Dollars had not been released in the U.S., no inkling of the kind of western the director had in mind. At Eastwood’s urging, he nipped out to a local cinema and returned with the understanding that the script was “definitely second to style.” Van Cleef was easy to work with, and although he could put away a fair amount of liquid refreshment it never interfered with his work. He came ready for direction.

Leone had not wanted to make a sequel. His original plan was a caper picture called Grand Slam or a remake of Fritz Lang’s classic M to star Klaus Kinski or an autobiographical drama – Viale Glorioso – set in the 1930s. Jolly, the producers of A Fistful of Dollars, offered him a 30 per cent profit share on that film if he made a sequel, as they felt he was legally obliged to do. Instead, furious with his treatment at their hands, the director hit upon the title of a sequel For a Few Dollars More, the actual storyline only coming to fruition when he came across a treatment called The Bounty Killer by Enzo dell’Aquilla and Fernando Di Leo, who in exchange for a large sum, surrendered their screen credits. Luciano Vincenzoni completed the screenplay in nine days, leavening it with humor, after the director and his brother-in-law Fulvio Morsella had produced a revised treatment, Leone also involved in the final screenplay.

Leone found a new backer in Alberto Grimaldi, an Italian entertainment lawyer who worked for Columbia and Twentieth Century Fox and had produced seven Spanish westerns. He promised to triple the first film’s budget to $600,000, with the director on a salary and 50 per cent profit share.

Success bred artistic confidence. A Fistful of Dollars had broken all box office records in Italy, grossing $4.6 million, and so Leone sought to improve on his initial offering and develop an “authorial voice.”

Thematically, with two principals, initially rivals who end up as “argumentative children,” it took inspiration from westerns like The Bravados (1958) – the photo and the chiming watch – and Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz which pitched Burt Lancaster against Gary Cooper. While bounty hunters had cropped up in Hollywood, they were not ruthless killers, actions always justified, rather than merely professionals doing their job. So in some sense Leone was drawing upon, and upending, films like Anthony Mann’s The Naked Spur (1953) and The Tin Star, Andre De Toth’s The Bounty Hunter (1954) and Budd Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome (1959). Just as Clint Eastwood’s bounty hunter underwent change, gradually the character played by Gian Maria Volonte evolved from a straightforward outlaw called Tombstone to a stoned, sadistic bandit named El Indio.

With artistic pretension came attention to detail. Leone required historical exactitude not just relating to weapons used, but their ballistics and range. Lee Van Cleef’s arsenal included a Buntline Special with removable shoulder stock, Colt Lightning pump action shotgun, Winchester ’94 rifle, and a double-barreled Lefaucheux. Carlo Simi’s town, constructed near Almeria, contained a two-storey saloon, undertaker’s parlor, barbershop, telegraph office, jail, hotel and an adobe First City Bank. And there was nothing pretty about it. The saloon was dirty and overcrowded, machines belching so much smoke it “looked as if a man could choke in there.” Filming took place between mid-April and the end of June 1965.

Perhaps the biggest area for improvement was the music. Ennio Morricone had scored another nine films since A Fistful of Dollars. Both director and composer had ambitious ideas about how to use the music. The score was not recorded in advance, nor was Morricone given a screenplay, instead listening while Leone told him the story and asked for individual themes for characters. Morricone would play short pieces for Leone and if met with his approval compose longer themes. Each character had their own leitmotif, sometimes the same instrument at different registers, the flute brief and high-pitched for Monco (Eastwood) but in a low register for Mortimer, church bells and a guitar representing El Indio. In a very real sense, they were experimenting with form. Bernardo Bertolucci regarded Morricone’s music as “almost a visible element in the film.” Musical ideas regarding El Indio’s watch, however, were developed at the rough cut stage, its repetitive melody becoming “sound effect, musical introduction and concrete element in the story.”

As well as creating music for audiences, Leone’s films are punctured with music that holds particular meaning for characters, here the watch and in Once Upon a Time in the West the harmonica, in both films flashback used to assist understanding.

The myth of why it took so long for either film to reach the United States was based on two misconceptions, firstly that Japanese director Akira Kurosawa, whose Yojimbo (1961) A Fistful of Dollars closely resembled, had blocked its progress, secondly that it relied on screenwriter Vincenzoni to make the breakthrough via a contact working for United Artists.

In fact, there were more obvious reasons for resistance from American distributors. In the first place, you could not discount snobbery. The notion that the country that had invented the western should now be reliant on importing them from Italy seemed a shade abhorrent. Although For a Few Dollars More was sold to 26 countries in a day at the annual Sorrento trade fair in 1965 – at the same fair a year earlier there had not been a single taker for A Fistful of Dollars – the United States was not among the buyers, distributors perhaps even more daunted by the prospect of introducing so much violence to American audiences reared on the traditional western.

Foreign movies that made the successful transition to the United States arrived weighted down with critical approval and/or awards or garlanded with a sexy actress – Brigitte Bardot, Anna Magnani, Sophia Loren among the favored – and risqué scenes that Hollywood dare not include for fear of offending the all-mighty Production Code.

But sex was a far easier sell in the U.S. than violence. And an actor with no movie marquee such as Clint Eastwood did not fill exhibitors with delight and even the notion that A Fistful of Dollars was a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) failed to stir the critics (as with The Magnificent Seven being a remake of Seven Samurai, most viewing the notion as repellent). So both the first and second pictures in the “Dollars” trilogy were stuck in distribution limbo for three and two years, respectively, before being screened in America.

And, initially, it had appeared that Italian audiences shared the same distaste for a cultural intruder such as A Fistful of Dollars. One cinema chain owner refused to book the film on the grounds that there were not enough female characters. A Fistful of Dollars was released in Italy in August, a dead period, since the month is so hot and everyone has abandoned the city for the beach. It opened – only in Florence and with neither publicity nor advertising – on August 27th 1964, a Friday, and did poor business that day and the next. But by Monday, it was a different story, takings had doubled and over the following two days customers were being turned away. New films typically played first-run for 7-10 days in Florence, A Fistful of Dollars ran for three months, triggering a box office story of Cinderella proportions.

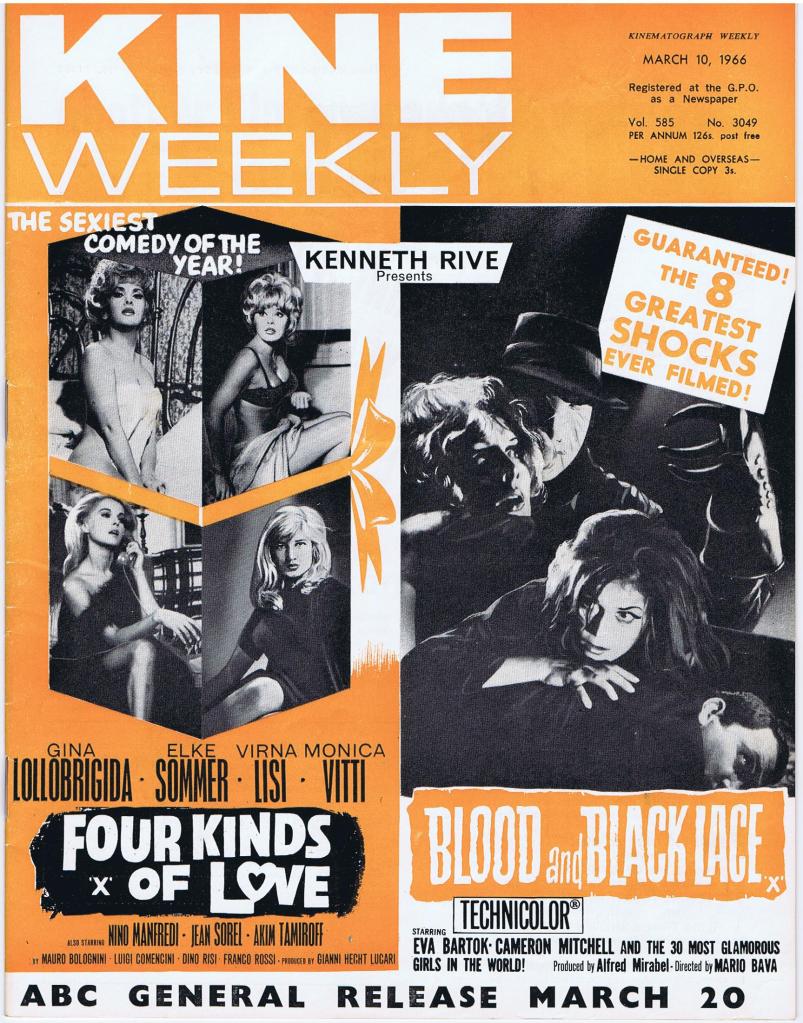

But my research indicated there had been ample opportunity for an American distributor to snap up the rights to A Fistful of Dollars in 1965, two years before it was finally released there. In the first place, the music rights had already been purchased by New York firm South Mountain Music in March 1965 in expectation the film would acquire release that year. In December 1965 Arrigo Colombo, partner in Jolly, flew to the United States for the specific purpose of lining up a major distributor for A Fistful of Dollars. The company had previously secured U.S. distribution for horror product like Castle of Blood (1964) and Blood and Black Lace (1964) but those were outright sales.

With the movie already sold to Spain, West Germany, France and Japan, Colombo aimed to conclude a deal for the English-speaking market, “purposely holding back” from releasing the picture in those countries as he sought an all-encompassing contract. At that point, Kurosawa no longer stood in the way, that issue “now cleared up” settled in the normal fashion by financial inducement, in an “amicable settlement” Toho snagging the Japanese and Korean rights, the deal sweetened with a minimum $100,000 against a share of global profits. But Colombo went home empty-handed, unable to secure any deal and his temerity ridiculed by trade magazine Variety

Although Sergio Leone had one other legal obstacle to surmount that would not have got in the way of a U.S. distribution deal, the worst that could happen being that a contract might be struck with a different company. Italian companies Jolly Films/Unidis, which had backed the original, took umbrage at Leone going ahead with the sequel without their financial involvement, cutting them off from the profit pipeline. So in April 1966 they took Leone to court in Rome arguing that For A Few Dollars More “represented a steal as well as unlawful competition for its own Fistful.” Four months later the judge denied the claim on the grounds that “the character played by Clint Eastwood in each film is not characterized to such a degree that a likeness exists” (even though to all intents and purposes it was the same character, cigar, poncho, gun, bounty hunting!). Ironically, Italian laxity in such matters counted against Eastwood when he failed to prevent the distribution of a film based on two segments of Rawhide stitched together.

It would also be highly unusual if United Artists was not aware of both A Fistful of Dollars and For A Few Dollars More since, in keeping tabs on the foreign performance of both Goldfinger (1964) and Thunderball (1965) the studio could scarcely fail to notice the Italian westerns close on their box office tail, the second western outpointing Thunderball in daily averages in Rome.

But the story still, erroneously, goes that it was the intervention of writer Vincenzoni which proved decisive. He had contacts in U.S, namely Ilya Lopert of United Artists. Grimaldi was, meanwhile, trying to sell U.S. and Canada rights relating to the second picture. Vincenzoni arranged for UA’s representatives to view A Fistful of Dollars in Rome and cut himself in for a slice of the profits when the distributor surprisingly purchased the entire series.

Since A Fistful of Dollars had already been sold to most major territories, UA could only acquire the North American rights – for a reported $900,000 – but for the other two films gained a considerably larger share of global distribution

United Artists was an unusual company among the Hollywood hierarchy, and not primarily due to recurrent Oscar success, but because it had, completely unexpectedly, hit box office gold with James Bond. There was nothing particularly odd about a series, as Tarzan, Sherlock Holmes etc (still flourishing in the 1960s) testified. What was distinctive about the Bonds was that each picture – the four so far had earned close to $150 million worldwide, not counting merchandising – had done better than the last, which went against the standard rule of sequels of diminishing returns and higher costs. Given the opportunity to buy into a ready-made series (two films in the can, the third in production) UA made an “attempt to calculatedly duplicate the (Bond) phenomenon” and in so doing “create a trend.” Assuming the movies would follow the Bond formula of increased grosses with each successive picture, the studio was prepared to spend “many hundreds of thousands” of dollars to establish the first picture.

United Artists embarked on an unusual sales campaign to the trade. Instead of marketing the pictures one at a time, they started to promote the series with the tagline “A Fistful of Dollars is the first motion picture of its kind, it won’t be the last.” The advertising campaign was unusual in that it was based entirely around introducing the character rather than the story (much in the same way as James Bond had been), three separate slivers of the poster devoted to visual aspects, the cigar, gun and poncho, each carrying mention of “The Man With No Name,” such anonymity one of the talking points of the movies.

Cinema managers were briefed on release dates, A Fistful of Dollars in January 1967, the sequel for April and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly for Xmas that year. Like the Bonds, it was expected that box office would progressively, if not explosively, increase. The studio unveiled a “hard-hitting campaign” designed to “intrigue the western or action fan.”

However, the North American premiere was held not in the United States but Canada, at the Odeon-Carlton in Toronto. Having committed to a four-week engagement, a risky prospect for an unknown quantity, the cinema started advertising a teaser campaign three weeks in advance. During the first week, posters were not just focused on the “man with no name” but also “the film with no name” and the “cinema with no name,” all those elements removed from the artwork until the second week of the campaign. UA allocated $20,000 in marketing, up to four times the usual amount spent on a launch there, and was rewarded with strong results – “bullish but not Bondish” Variety’s verdict.

However, the UA gamble did not pay off, especially when taking into account the high cost of buying the rights allied to huge marketing costs. Initial commercial projections proved unrealistic. Despite apparently hitting the box office mark in first-run dates in key cities, the film was pulled up short by its New York experience. Shunted straight into a showcase (wide) release rather than a first-run launch, it brought in a pitiful $153,000 from 75 theaters – even The Quiller Memorandum (1966) in its second week did better ($150,000 from 25). As a consequence when For a Few Dollars More was released in April/May, UA held off boking it into New York until “a suitable arrangement” could be made, which translated into hand-picking a dozen houses famed for appealing to action fans plus 600-seat arthouse the Trans-Lux West.

United Artists predicted $3.5 million in rentals (the amount returned to studios after cinemas take their cut of the gross) for A Fistful of Dollars and $4.5 million with For a Few Dollars More. Neither came close, the latter the marginally better performer with $2.2 million in rentals (enough for a lowly 41st on the annual chart) with the first film earning $2.1 million in rentals (46th) way behind more traditional performers like Hombre ($6.5 million for tenth spot), El Dorado ($5.9 million in 13th) and The War Wagon ($5.5 million in 15th).

The vaunted Bond-style box office explosion never materialized and it might have helped if UA had kept closer watch on the actual revenues posted in Italy for the series. While For a Few Dollars More increased by $2 million the takings of A Fistful of Dollars, the final film in the trilogy, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly produced lower grosses than even the first.

However, it did look as if The Good, the Bad and the Ugly would come good. UA opened it in two first-run cinemas in New York where each house retained it for six weeks. But although the final tally of $4.5 million (24th spot in the annual rankings) was the best of the series, it did not herald returns that made it anywhere near comparable to the Bonds.

It’s possible the movies did better in terms of admissions than the box office figures show. Distributors pushing foreign product into arthouses were generally able to achieve a high share of the rental – 50 per cent the going rate – because they were able to set rival arthouses against each other and movies with a sexy theme/star had inbuilt box office appeal, La Dolce Vita (1960) and And God Created Women (1956) the classic examples. But that would not be possible when trying to interest ordinary cinemas with a film lacking in sex.

When I researched the early Bonds for a previous Blog, I found that United Artists had only managed to achieve bookings for Dr No (1962) by lowering its rental demand. Exhibitors paid the studio just 30 per cent of the gross. And I wondered if perhaps the same occurred with A Fistful of Dollars given the star, like Sean Connery, was completely unknown. Of course, it would not explain why the series did not grow as expected.

Of course, there was a surprising winner and an unexpected loser in the whole ‘Dollars’ saga. Clint Eastwood emerged as the natural successor to John Wayne with a solid box office – and later critical – reputation for American westerns starting off with Hang ‘Em High (1968) which beat The Good, the Bad and the Ugly at the box office, while Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1969) proved a huge flop in the U.S.

Christopher Frayling, Sergio Leone, Something To Do With Death (Faber & Faber, 2000), p160-162, p165-200; “Italo’s Own Oater Leads Box Office,” Variety, December 2, 1964, p16; “South Mountain Buys Dollar Score,” Variety, March 10, 1965, p58; “Jolly’s Colombo Discovers N.Y.C. Busy at Xmas,” Variety, December 22, 1965, p3; “Tight Race for Box Office Honours in Italy Looms as Thunder Leads Dollars,” Variety, January 65, 1966, p15; “Dollars World Distribution for UA,” Variety, March 22, 1966, p22; “Clint Eastwood Italo Features Face Litigation,” Variety, April 13, 1966, p29; “UA Cautious on Links to Italo Fistful; Faces Slap from Kurosawa,” Variety, July 13, 1966, p7; “Rome Court Rejects Plea for Seizure of Few Dollars Made By Fistful Film,” Variety, August 3, 1966, p28; “Clint Eastwood vs Jolly on 2 Segs of Rawhide ‘Billed’ New Italo Pic,” Variety, September 7, 1966, p15; “Italy Making More Westerns, Spy Films Than Star Vehicles,” Box Office, October 31, 1966, p13; “Hemstitched Feature,” Variety, November 23, 1966, p22; “UA Division Holds Screenings of Westerns,” Box Office, December 12, 1966, pE2; Advertisement, Variety, December 21, 1966, p12-13; “UA Gambles Dollars As Good As Bonds,” Variety, December 28, 1966, p7; “Fred Goldberg Shows Ads on UA ‘Dollar’ Films,” Box Office, January 2, 1967, pE4; “Review,” Box Office, January 9, 1967, pA11; “Fistful of Dollars: Male (and Italo) B.O.,” Variety, January 18, 1967, p7; “Fistful of Dollars: The Glad Reaper,” Variety, February 1, 1967, p5; “This Week’s N.Y. Showcases,” Variety, February 8, 1967, p9; “Fistful’s Weaker N.Y. B.O. Clench,” Variety, February 8, 1967, p7; “Methodical Campaign Kicks Off Ideal Fistful Ballyhoo in Toronto,” Box Office, May 1, 1967, pA1; “Few Dollars More Runs 30% Ahead of First Dubbed Italo-Made Western, So Bond Analogy Makes Out,” Variety, May 31, 1967, p4; “N.Y. Slow to Fall Into Line,” Variety, May 31, 1967, p4; “B’way Still Boffo,” Variety, July 12, 1967, p9; “Carefully Picked,” Variety, July 12, 1967, p4; “B’way Biz Still Big,” Variety, July 19, 1967, p9; “Big Rental Films of 1967,” Variety, January 3, 1968, p25; “B’way B.O. Up,” Variety, January 31, 1968, p9; “Big Rental Films of 1968,” Variety, January 8, 1969, p15.