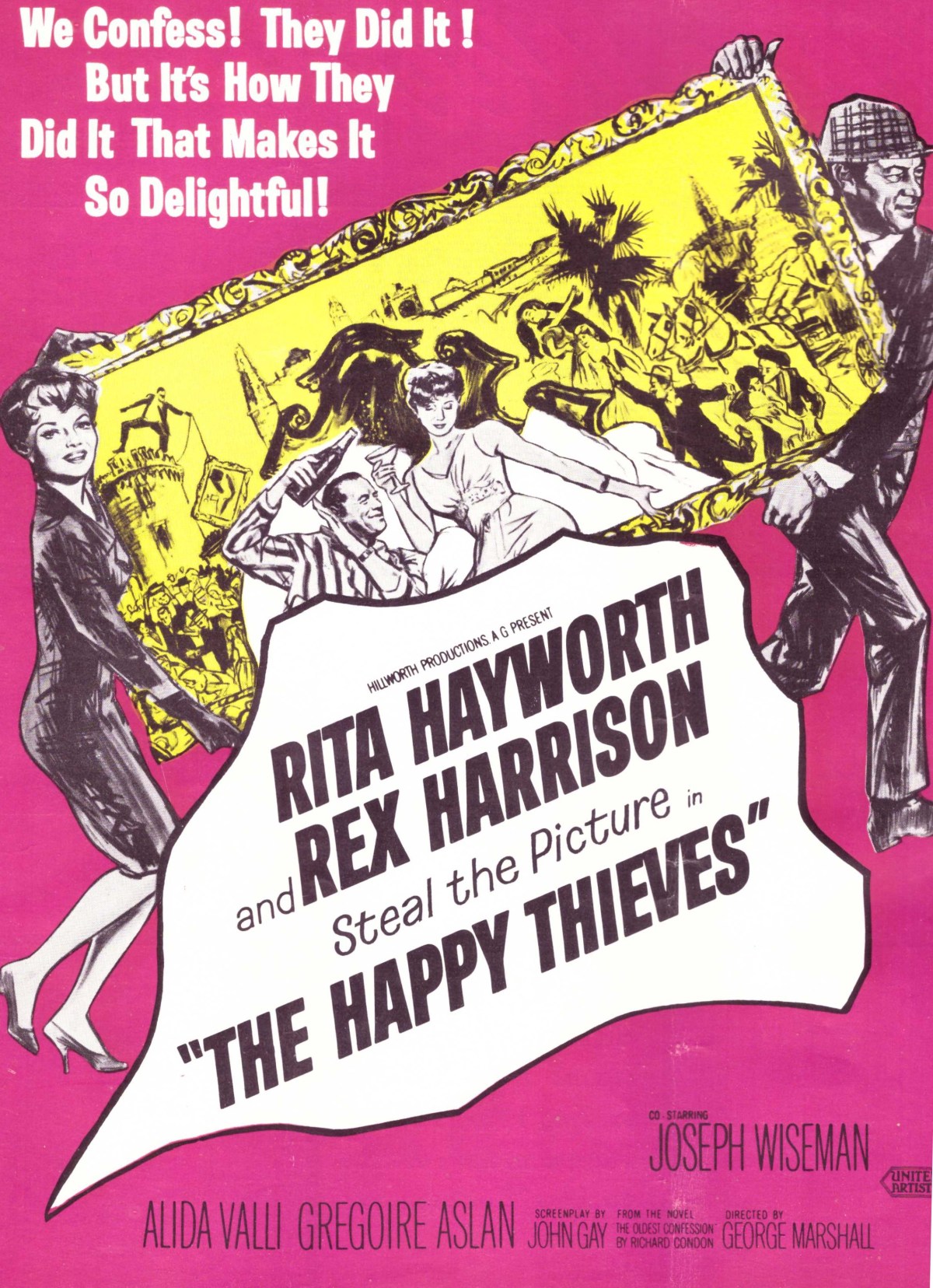

A triumvirate of art thieves are blackmailed into stealing a famous Goya painting from the Prada museum in Madrid. Jimmy Bourne (Rex Harrison) is the actual thief, Eve Lewis (Rita Hayworth) smuggles the artworks out of the country and Jean-Marie (Joseph Wiseman, soon to be more famous as Dr No, 1962) creates the forgeries that replace the stolen masterpieces. Hayworth is the least reliable of the trio, her drinking (she had a problem in real life) jeopardizes their slick operation. Not only has the painting they have stolen slipped through her hands but the thief Dr Victor Munoz (Gregoire Aslan) has filmed the original theft and is not above a bit of murder on the side.

Harrison and Hayworth are a delightful pairing. Hayworth has abandoned the sultry in favor of the winsome, Harrison shifted from sarcasm to dry wit. He is always one-step-ahead but never overbearing, and the thefts are carried out with military precision. Even when let down by colleagues, who are inclined to scarper when threatened, he takes it all in his stride, the calm center of any potential storm. And there is genuine chemistry between Harrison and Hayworth though his matter-of-fact attitude tends to undercut the kind of passionate romance that moviegoers came to expect from top-class players thus paired. His proposal, for example, comes by way of dictation, “the new Mrs Bourne.” It would have been tempting for Hayworth to act as the ditzy blonde (brunette, actually) but instead she plays it straight, which is more effecting.

Bourne is the archetypal gentleman thief (“there is a touch of larceny in all successful men”) and Eve does her earnest best to keep up (“I want so much to be a first-class crook for you, I’m trying to be dishonest, honestly I am.”) There is never the remotest chance of them being confused with real gangsters. “I thought that stealing was the only honest way Jimmy could live with himself,” says Eve. In truth, their characters set the template for better-known later heist pictures like How to Steal a Million (1966), Gambit (1966) and A Fine Pair (1968) – all reviewed on this blog – which couple one determined thief with one less so.

Of course, heist pictures rely for much of their success on the actual heist. And Bourne’s plan for the Prada is brilliantly simple and carried out, as mentioned, with military precision. The get-out clause, which, of course, is how such films reach their conclusion, is more realistic and human than the other movies I have mentioned.

What’s more, there are number of excellent sight gags and great throwaway lines while Jean-Marie and Dr Munoz are well-written, the villain’s motivation particularly good. Other incidentals lend weight – their apartment is opposite a prison, the security guards at the Prada are caring rather than the idiots of How to Steal a Million, and a sub-plot involving a bullfighter (Virgilio Teixeira, Return of the Seven, 1966) also sheds light on Bourne. There is a jaunty whistling theme tune by Mario Nascimbene (One Million Years B.C., 1966) which maintains levity throughout.

The movie does tilt from the gentleman thievery of the initial section into something much darker, but, so too, do the two principals and, unusually, rather than in the usual contrived fashion, Bourne and Eve undergo personal transition by the end.

I found the whole exercise highly enjoyable. It’s very under-rated. My only quibbles are that it is shot in black-and-white, which seems bizarre when Spain, the location, is such a colorful country. The title, too, is an oddity. This was the only picture produced by Hayworth in partnership with husband James Hill. They split up before the picture was released which might explain its poor initial box office. Hill was an experienced producer, part of Hill-Hecht-Lancaster (The Unforgiven, 1960), but this proved his final film.

Hayworth, too, had previously worn the producer’s hat for The Loves of Carmen (1948), Affair in Trinidad (1952) and Salome (1953). Hayworth was still a marquee attraction at this point, taking top billing here, and second billing to John Wayne in Circus World/The Magnificent Showman (1963). But this is quite a different performance to her all-out-passionate persona or the slinky deviousness of Gilda (1946). Alida Valli (The Third Man, 1949) puts in an appearance and trivia trackers might take note of the debut of Britt Ekland (credited as Britta Ekman).

Director George Marshall was a Hollywood veteran with over a quarter of a century directorial experience including film noir The Blue Dahlia (1946), Jerry Lewis comedy The Sad Sack (1957) and western The Sheepman (1958) with Glenn Ford. In fact, five of his previous six pictures had starred Glenn Ford and his next shift would be on How the West Was Won (1962).