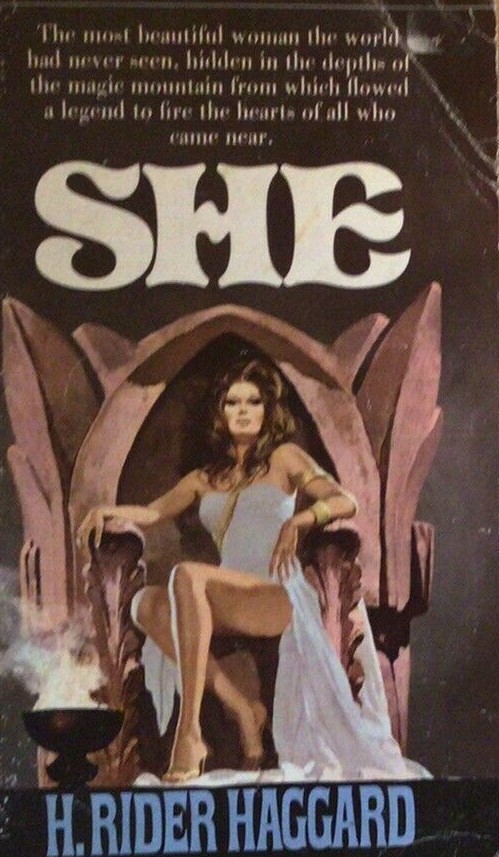

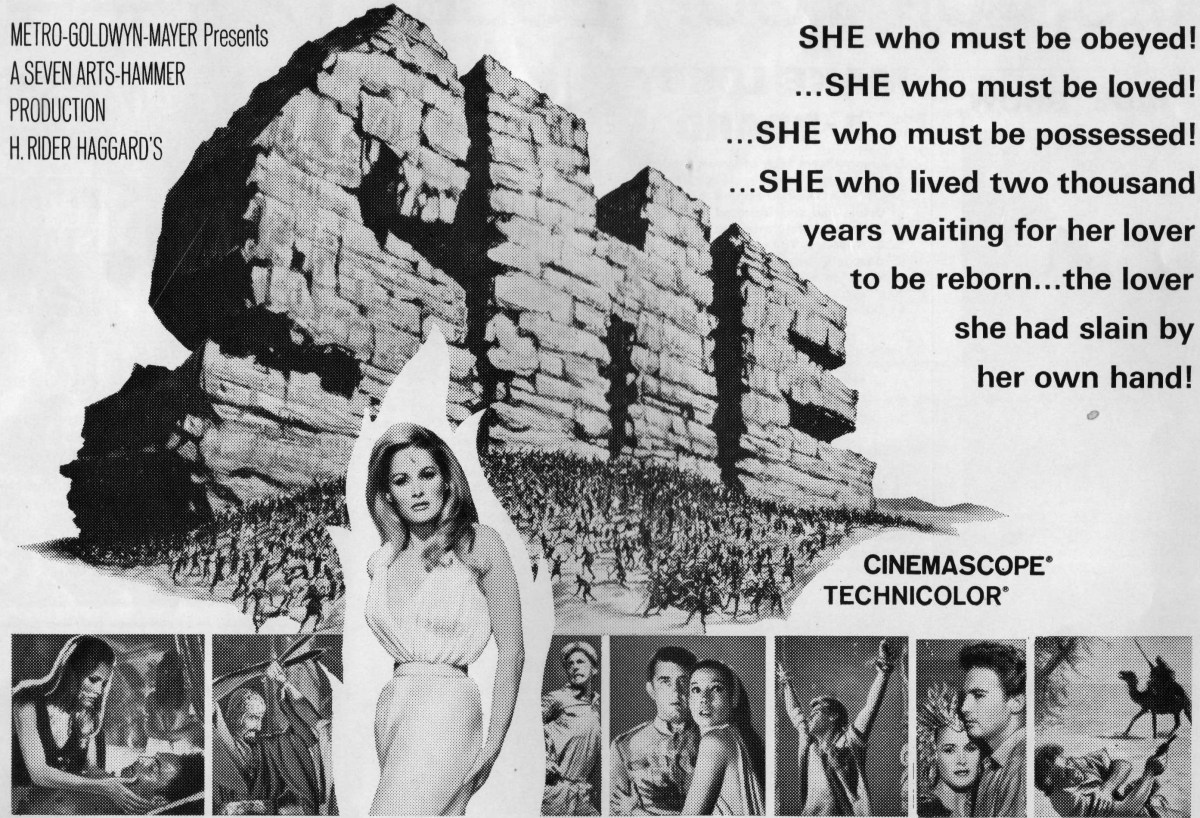

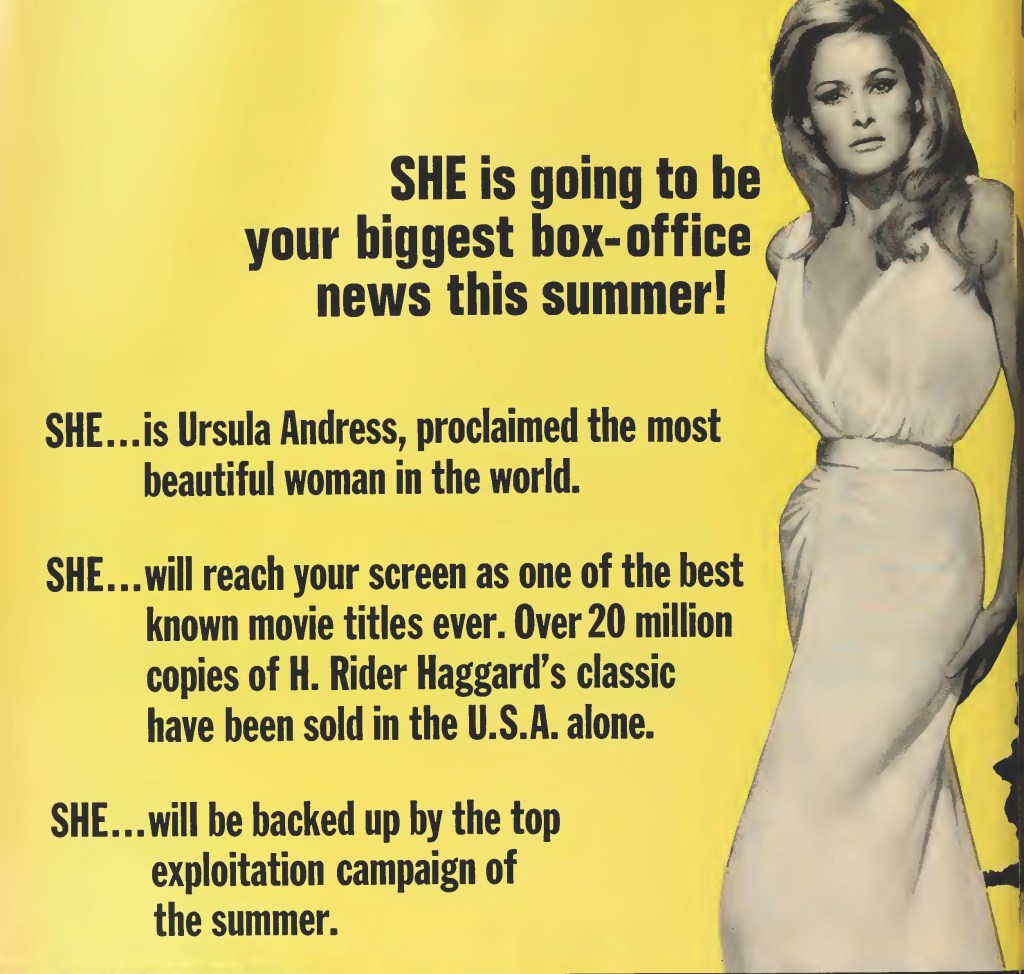

Novelizations were the hidden secret of 1960s Hollywood. While the decade is better known for widescreen 70mm roadshows, James Bond and the spy deluge, the musical and western revival and the start of the American New Wave, the novelization revolutionized the way films were marketed. By the end of the decade virtually every film released was accompanied by a book tie-in, either a bestseller sold to Hollywood, or a film script turned into a paperback / soft cover book.

At the start of this boom, around 1960, studios virtually gave away screenplays to publishers and allowed them to turn them into novels in return for the marketing angle they could provide. “Producers looked at tie-in books primarily as an exploitation aid not a source of income,” explained Patricia Johnson of paperback specialist Gold Medal Books in 1962. “Motion picture companies with no more – and often much less – than a rough script are being besieged by droves of publishers vying for the right to novelize original scenarios.”

The novelizations were usually short – about 60,000 words – and therefore attractively priced for the reading public but they could sell as many as half a million copies. But except in particular circumstances, studios allowed the rights to go to publishers for minute amounts of money. And for one simple reason – marketing. Half a century before social media, there was little advance promotion of movies. The week they were about to be released would see a flurry of advertising, but in general little promotion before that. Even journalists who had attended the press junkets I mentioned in a previous Blog would concentrate their articles into the week of release.

“What a publisher does for a film concern,” said Johnson, “is it creates a nationwide market, a popular anticipation of a film before it would ordinarily be more than a vague glimmer in the public consciousness.” The 125,000 outlets for books included not just bookstores but locations that targeted passing trade with extensive foot traffic. Newsstands in the street, hotel lobbies, railroad stations, department stores, airports and drugstores all boasted racks of paperback books with glossy covers, informing potential moviegoers of forthcoming films. Studios wanted to take advantage of the promotional device that bestsellers turned into movies could generate. For studios they represented an early marketing tool. Incorporating the movie advert or photos of the stars raised awareness of a forthcoming picture long before the first advert had appeared in a newspaper or billboard.

One of the earliest novelizations was for Rat Pack heist picture Ocean’s 11 (1960) – pictured at the top of this page – and it showed the format to which publishers readily adhered. As you might expect, the cover featured a still from the movie incorporating the main stars, but there was also, by dictat of the Writers Guild of America (the screenwriters union), mention of the original scriptwriters in the same size of typeface as the authors who had carried out the novelisation.

Very rarely did the original screenwriter undertake this task. For a start, most considered it beneath their dignity. But, secondly, they got paid anyway. The screenwriter automatically received one-third of the fee a publisher paid the studio and the same share of royalties. By the mid-1960s the WGA was negotiating for a set fee of $6,000 (about $50,000 equivalent now) so a nice amount for no work but less appetising for a full-time screenwriter to do the whole job.

But there were exceptions. Robert Bloch decided to turn his original screenplay The Couch (1961) into a novel. But then he had the experience of Psycho (1960) behind him. Prior to the 1960 Hitchcock film, his novel had only sold only 4,000 copies in hardback. The success of the film shifted 500,000 copies in paperback. Bloch must have reckoned his name emblazoned on the cover – and gaining sole credit, fee and royalties – would be more financially beneficial. Western author James Warner Bellah undertook the novelizations of his screenplays for Sergeant Rutledge (1960), A Thunder of Drums (1961) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

But neither would have been as assiduously wooed by publishers as the team of Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick who were jointly credited for the novelization of 2001: A Space Odyssey. An extremely unusual aspect of this deal was that the novelization appeared first as a hardback. Although based on a Clarke short story, and despite the fact that Clarke was considered one of the greatest names in science fiction, on the writing side movie and book were promoted as joint efforts. Delacorte-Dell forked out a $150,000 advance for the hardback with a 15% royalty rate. Clarke/Kubrick refused to allow the hardback publisher a share of the paperback spoils for which they negotiated a 12-15% royalty, way above the norm.

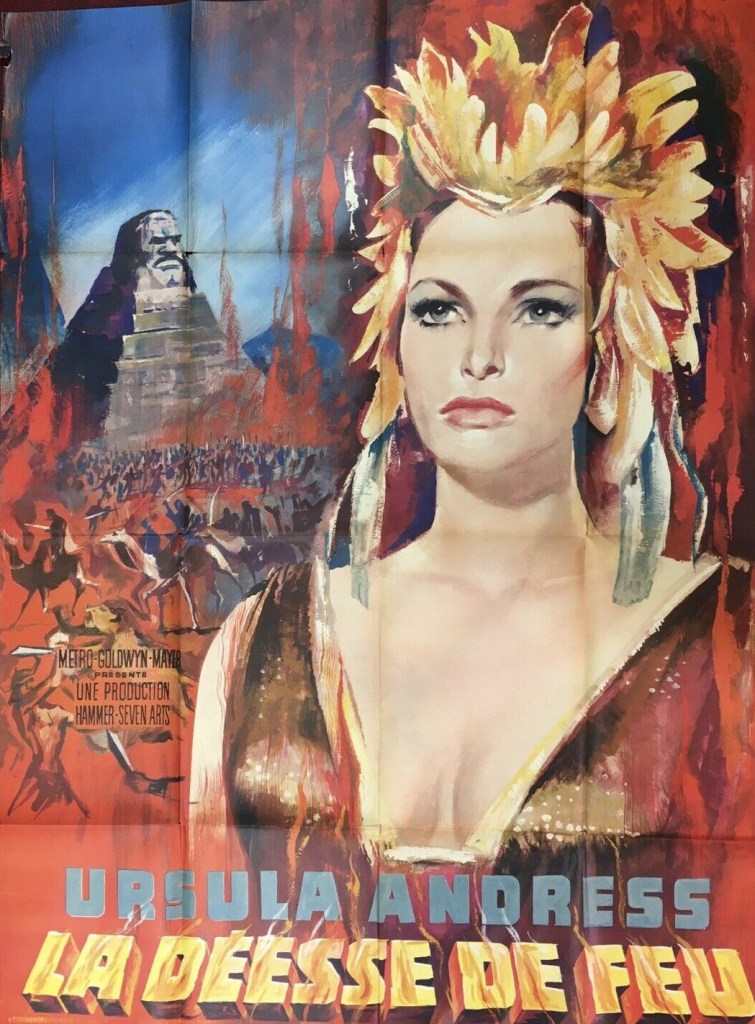

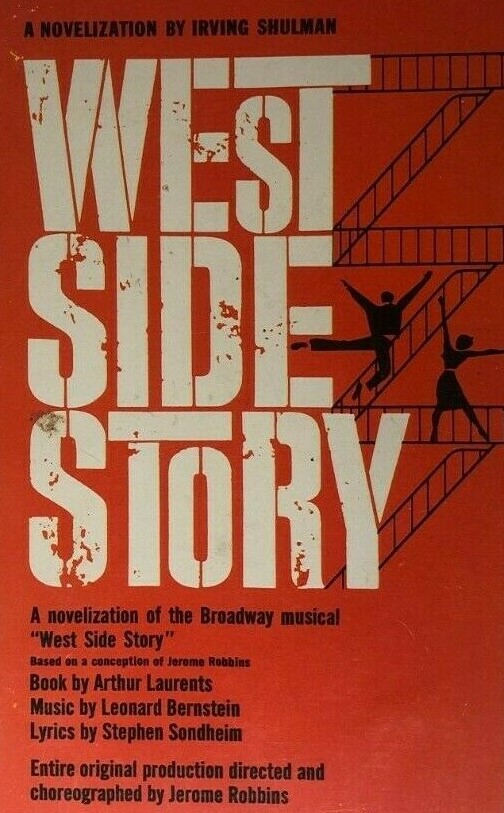

Occasionally the novelization would be undertaken by an author famous in their own right, such as when another sci fi giant Isaac Asimov took on the task of writing the book based on the script of Fantastic Voyage (1966). Famed western writer Louis L’Amour was handed the novelization of James Webb’s script for How the West Was Won (1963). Irving Shulman was a well-known novelist when called upon to turn West Side Story (1961) and The Notorious Landlady (1962) into novels. Screenwriter Adela Rogers St John (The Girl Who Had Everything, 1953) novelized King of Kings (1961). Sci fi writer Robert W. Krepps churned out novelizations for historical epics El Cid (1961) and Taras Bulba (1963), comedy Boys Night Out (1962) and westerns Stagecoach (1966) and Hour of the Gun (1967). Crime writer Jim Thompson novelized James Lee Barrett’s script of western The Undefeated (1969).

Some who took the novelization coin later made their name as bestselling authors in the own right. Marvin H. Albert – later known for the “Tony Rome” private eye novels that were filmed starring Frank Sinatra – was a relatively unknown journeyman writer when he became the go-to author for comedy novelizations, lending his name to the books of Come September (1961), Lover Come Back (1962), Move Over Darling (1963), The Pink Panther (1963), The Great Race (1965) and Strange Bedfellows (1965). Similarly, David Westheimer, a year before he published the bestselling Von Ryan’s Express, knocked out the book of Days of Wine and Roses (1962) from the J P Miller screenplay.

But mostly the novelizations were produced by journeymen such as Richard Wormer (Operation Crossbow, 1965), Alan Caillou (Khartoum, 1966), Ed Friend (Alvarez Kelly, 1966), John Burke (Privilege, 1967), Richard Meade (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967), Ray Gaulden (Five Card Stud, 1967), Jackson Donahue (Divorce American Style, 1967), Michael Avallone (Krakatoa-East of Java, 1968) and Joseph Landon (Stagecoach, 1966).

Publishers were not above picking over the spoils of decades-old scripts. Borden Deal was hired to novelize an un-made 1933 script written by Theodore Dreiser, author of An American Tragedy; Johnny Belinda (1948) was novelized in 1961. There were other departures. When writer-director S.Lee Pogostin received a $10,000 advance to novelize his own Hard Contract (1969) the book that appeared comprised the original script with stage directions and filmic addenda, in part due to the success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance (1969) which was published as a screenplay rather than being novelized.

No genre was safe. Even musicals were plundered for their appeal to the book-reading public or for moviegoers wanting another way of reliving the film they had seen or getting a flavor of a picture they might consider seeing. As well as West Side Story and The Music Man (1962), there were novelizations of My Fair Lady (1964), Funny Girl (1968) and Paint Your Wagon (1969), an unexpected bestseller thanks to Clint Eastwood and Lee Marvin on the cover.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. Hollywood was notoriously lax when it came to release dates, the opposite of the publishing industry for whom such dates were sacrosanct. So a publisher could have put a great deal into organizing the delivery of hundreds of thousands of copies of a novelized title into over a hundred thousand outlets only for the book to molder away on the shelves waiting for a movie which arrived months late – or never at all. Or the movie might undergo a last-minute title change leaving publishers trying to flog a picture nobody had heard of.

SOURCES: “3-Yr Advance Campaign for King of Kings,” Hollywood Reporter, July 5,1961, p2; “Book Notes,” Hollywood Reporter, October 27, 1961, p9; “Book Notes,” Hollywood Reporter, December 5, 1961, p11; Patricia Johnson, “Ego, Yes, Indecision Often, But Love That Hollywood,” Variety, January 10, 1962, p42; “How the West Was Won with L’Amour,” Hollywood Reporter, January 26, 1962, p10; “Book Notes,” Hollywood Reporter, December 5, 1961, p11 “Book Notes,” Hollywood Reporter, January 17, 1962, p7; ; “Willson Novelizing Script,” Hollywood Reporter, February 5, 1962, p3; “Book Notes,” Hollywood Reporter, April 3, 1962, p8; “Book Notes,” Hollywood Reporter, August 15, 1962, p7; “Roger Lewis, Phil Langner and Corp Ready Garrick Production Slate,” Variety, November 13, 1963, p19; “Crossbow Books Tie In with Picture Release,” Box Office, May 31, 1965, pA2; “Stagecoach Screenplay To Become Paperback,” Box Office, March 14, 1966, pA1; “Signet Print Paperback of Cinerama Khartoum,” Box Office, June 13, 1966, pA1; “Divorce American Style Film and Book Tie-Up,” Box Office, June 20, 1966, p12; “Inside Stuff – Pictures,” Variety, August 10, 1966, p24; “Anti-Brush-Off of Writers,” Variety, November 16, 1966, p11; “Gold Medal Books to Print Alvarez Kelly Paperback,” Box Office, September 12, 1966, pA1; “Four Paperbacks Are Set On New Universal Films,” Box Office, September 19, 1967, pA2; “Sci Fi Award Goes To 20th-Fox for Voyage,” Box Office, September 26, 1966, pSW2; “Paint Your Wagon Set for Novelization,” Box Office, October 6, 1969, pA2; “The Undefeated Is Now Available in Paperback,” Box Office, November 3, 1969, pA2; “Inside Stuff – Pictures,” Variety, January 1, 1969, p23; “Advertisement, Krakatoa East of Java,” Box Office, November 17, 1969, p13-18; “Wagon Tie-In into Second Printing,” Box Office, December 1, 1969, pA2; “Marooned Printed in Paperback,” Box Office, December 15, 1969, pA1.