That Farewell, Friend / Adieu L’Ami (1968) was a smash hit in France did nothing for Charles Bronson’s Hollywood career. Hollywood had form in disregarding U.S.-born stars that Europe had taken to its box office bosom. Example number one of course was Clint Eastwood, ignored by the big American studios until four years after his movies had cut a commercial swathe through foreign territories. Charles Bronson took about the same length of time for his box office grosses abroad to make an impact back home.

While we tend to look upon The Dirty Dozen (1967) as a career-making vehicle for many of the supporting stars, that wasn’t actually the case. Jim Brown was quickest out of the blocks, a full-blown top-billed star a year later in The Split (1968). Otherwise, John Cassavetes had the biggest crack at stardom after landing the male lead in box office smash Rosemary’s Baby (1968). But the rest of the gang – Telly Savalas, Donald Sutherland, Charles Bronson, Richard Jaeckal et al – remained at least for the time being strictly supporting players.

For Charles Bronson, the year of The Dirty Dozen produced nothing more than television guest spots in Dundee and the Culhane, The Fugitive and The Virginian. Beyond that he had a berth in two flop westerns Villa Rides (1968) and Guns for San Sebstian (1968) and no guarantee his career was moving in an upward direction. But the latter picture was primarily a French-Mexican co-production, the Gallic end set up by top French producer Jacques Bar under the aegis of Cipra which had previously been responsible for Alain Delon vehicles Any Number Can Win (1963), Joy House (1964) and Once a Thief (1965).

There was another, as vital, French connection. Henri Verneuil directed both Any Number Can Win and Guns for San Sebastian so could attest to Bronson’s screen presence. And another legendary French producer, the Polish-born Serge Silberman, best known for Luis Bunuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), had taken note of Bronson, whose screen persona was similar to that of French stars Lino Ventura and Jean Gabin. Silberman’s Greenwich Films production shingle was in the process of setting up Farewell Friend / Adieu L’Ami.

Like The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968), Farewell Friend was part of a new trend to make French productions in English as well as French, in this case the English version viewed as “the working one.” But that ploy failed to convince U.S. distributors to take a chance and the film sat on the shelf for five years. And little that Bronson did in the meantime increased his chances of a serious stab at the Hollywood big time.

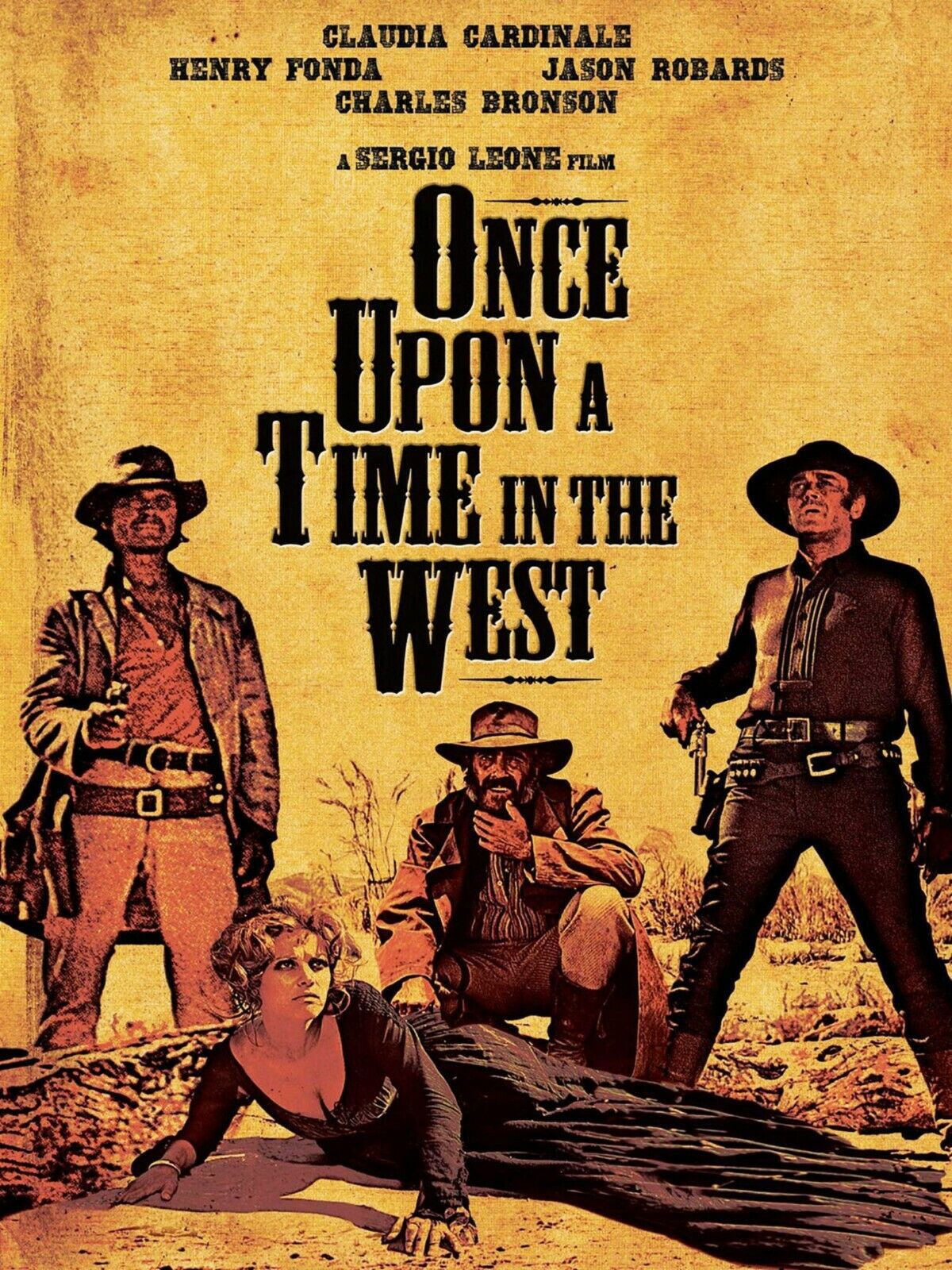

Although Paramount had piled cash into the Italian-made Once upon a Time in the West (1968) it was counting on Henry Fonda – undergoing a career renaissance after Madigan (1968), The Boston Strangler (1968) and Yours, Mine and Ours (1968) – to provide the box office momentum. Bronson was billed fourth after Claudia Cardinale, Fonda and Jason Robards, so still in Hollywood’s eyes a supporting player.

And while the Sergio Leone picture flopped Stateside, the success of Farewell, Friend in France turned Bronson into a star and was instrumental in the western breaking box office records in Paris (where it ran for a year) and throughout the country.

Fortunately for Bronson, European producers recognized his potential. His next picture should have been an Italian-French-German co-production of Michael Strogoff, for which he was announced as the top billed star (Advert, Variety, May 8, 1968, p136-137). When that fell through, Italian company Euro International, bidding to become the top foreign studio outside Hollywood, gave him top-billing in Richard Donner drama Twinky (aka Lola, aka London Affair, 1970) and Serge Silberman tapped him for Rene Clement thriller Rider on the Rain (1970), another French hit.

British director Peter Collinson (The Italian Job, 1969) was responsible for recruiting him for You Can’t Win ‘Em All (aka The Dubious Patriots, 1970), but with Tony Curtis taking top billing. Again, though funded by an American studio, this time Columbia, it was another big flop, mostly because the studio did not know how to market the picture, Curtis in a box office slump and Bronson considered to have little appeal.

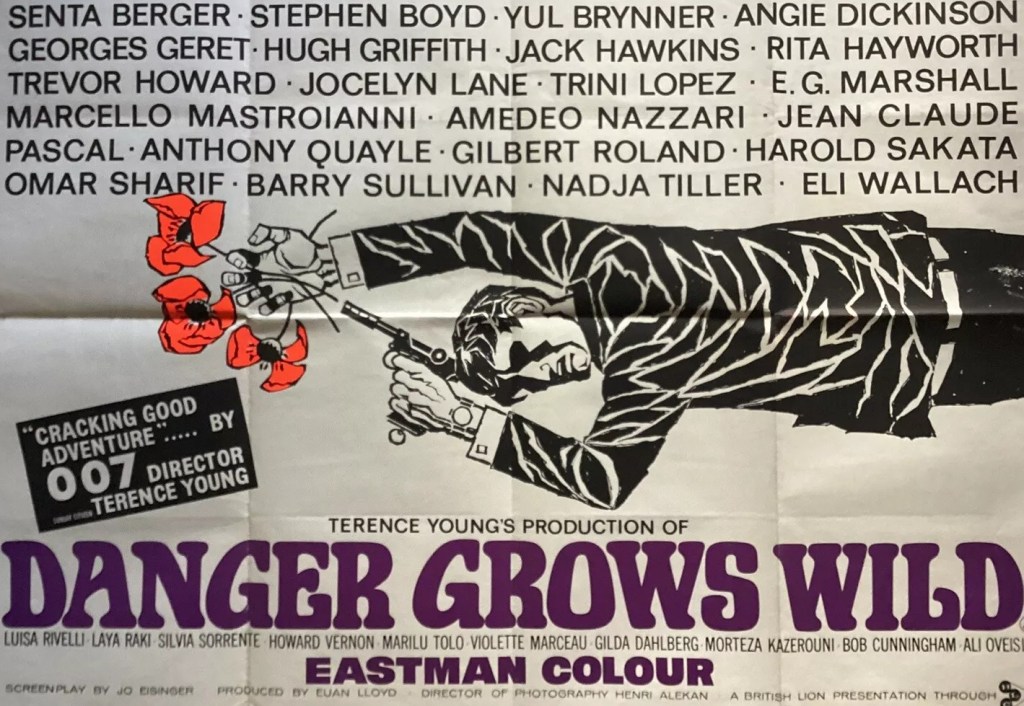

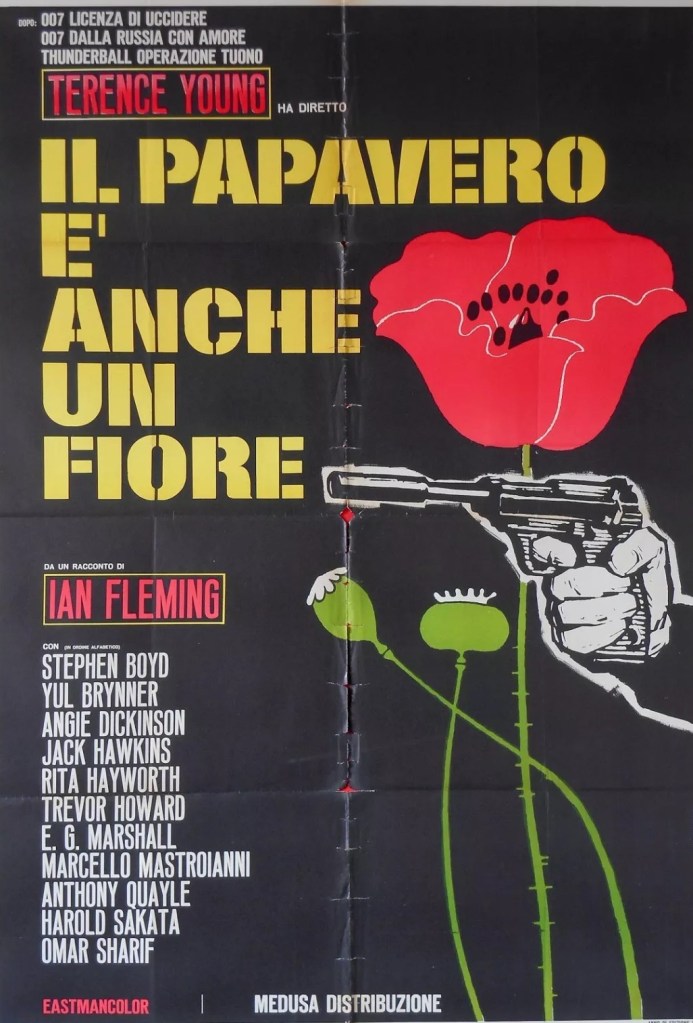

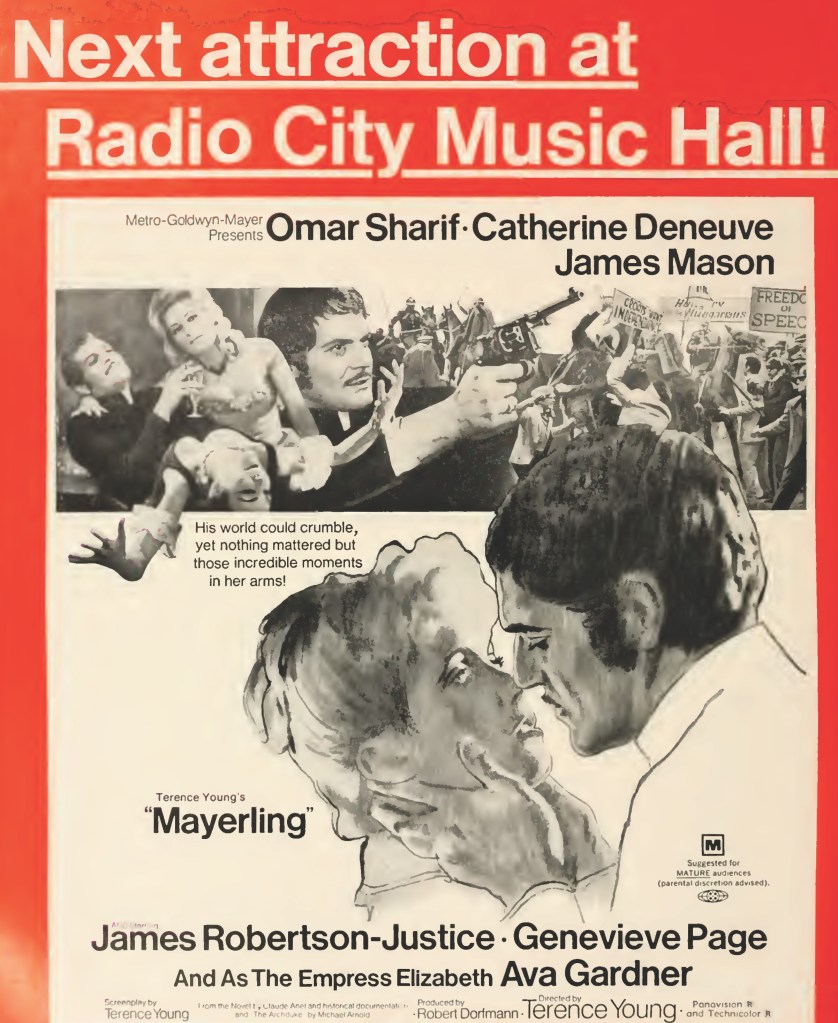

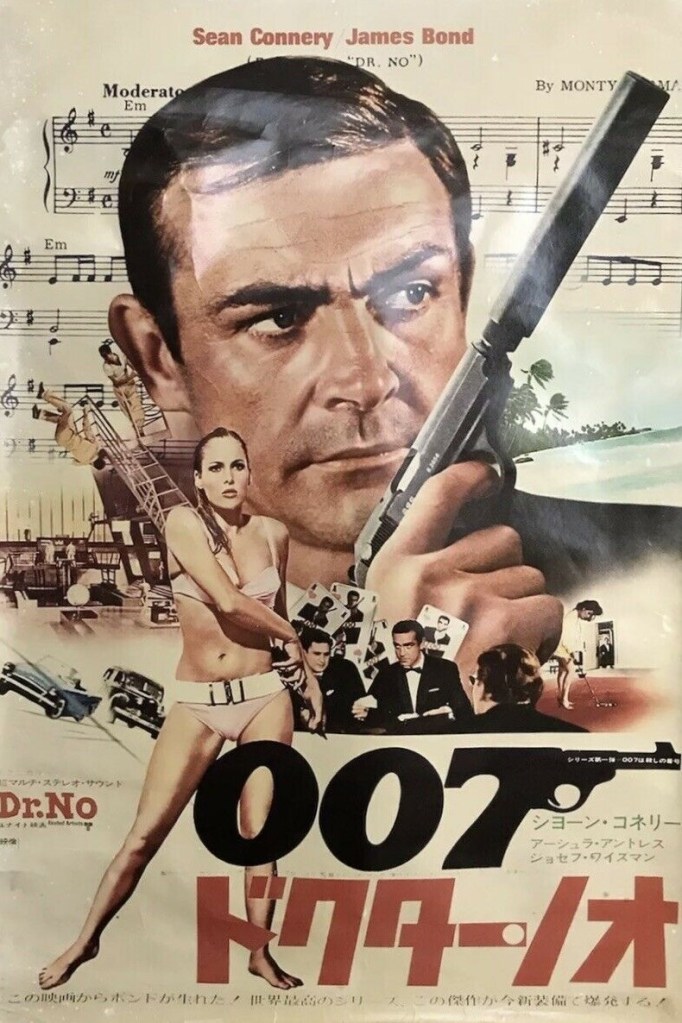

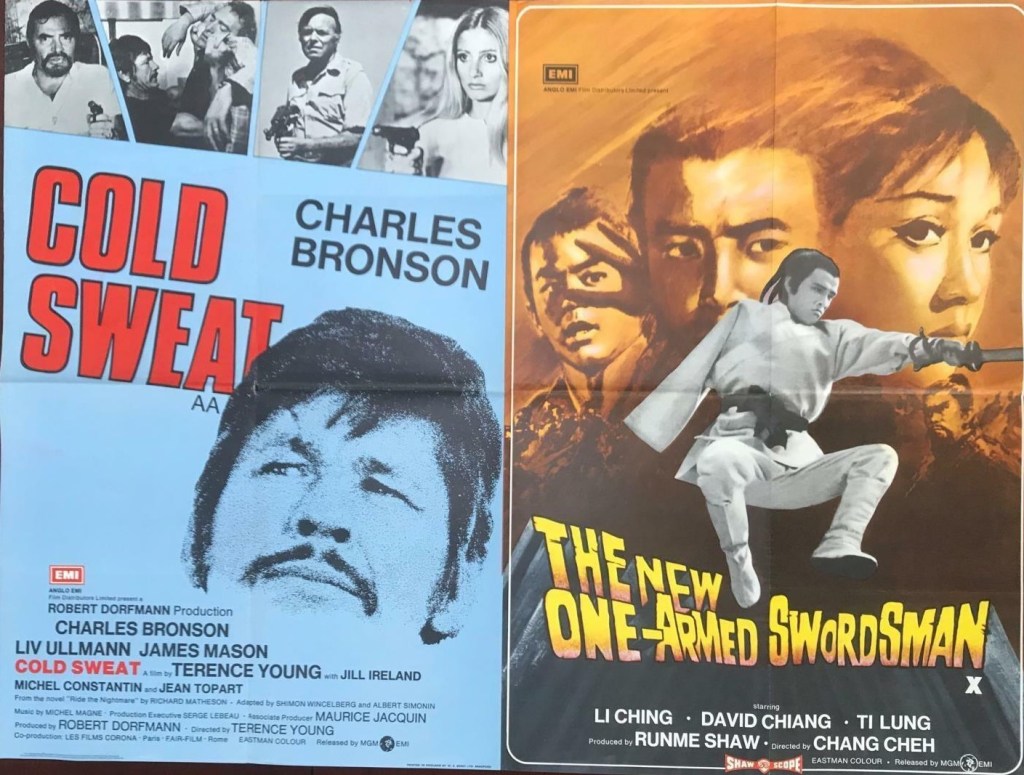

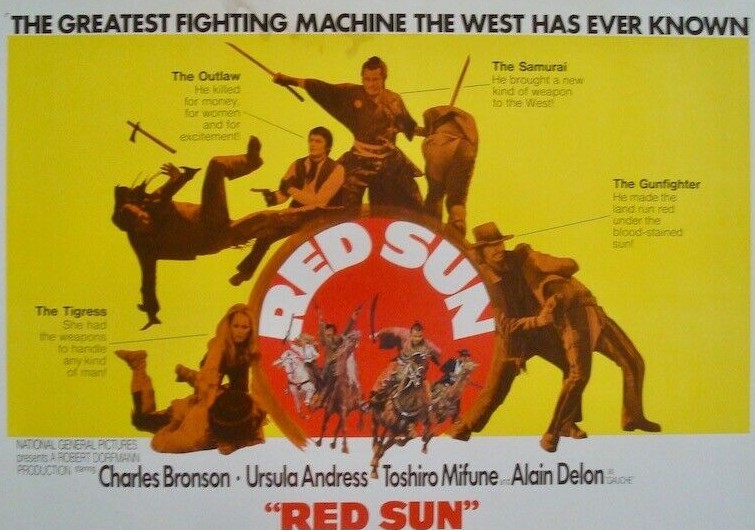

But still the Europeans kept the faith. Another French-Italian co-production Sergio Sollima’s Violent City (1970) gave him top billing over exiles Telly Savalas and Jill Ireland, Bronson’s wife. That was also the case with Cold Sweat (1970), helmed by British director Terence Young (Dr No, 1962). He had another French-made hit with Someone Behind the Door (1971) and Terence Young hired him again, along with Farewell, Friend co-star Alain Delon, Japanese star Toshiro Mifune (Seven Samurai, 1954) and Dr No alumni Ursula Andress for international co-production Red Sun. While this western sent box office tills whirring all over the world, it only made a fair impression in the U.S., ranking 53rd in the annual box office chase.

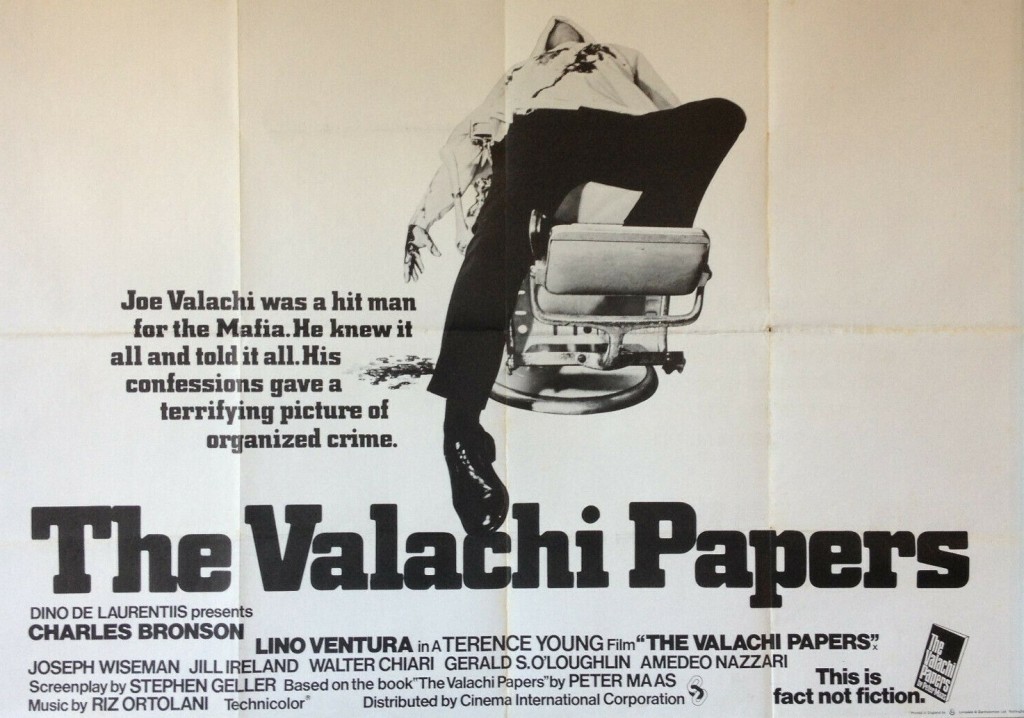

Riding on the back of The Godfather phenomenon, Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis chose Bronson for Mafia thriller The Valachi Papers (1972), again directed by Terence Young, which produced something of a box office breakthrough in the U.S., ending the year just outside the Top 20. But it took another British director, Michael Winner, to help solidify the Bronson screen persona and boost his global appeal. Four – and all of the hits – out of the star’s next six pictures were directed by Winner. These were the western Chato’s Land (1972), The Mechanic (1972), The Stone Killer (1973) and Death Wish (1975). The Mechanic was such a big hit Stateside it did better in its second year of release than the first and Columbia redeemed itself by giving prison escape thriller Breakout (1975) the widest release – up to that point – of all time.

That America had little interest in developing Bronson as a breakout star could be judged by the distribution treatment of his pictures. As mentioned above, Farewell, Friend had to wait until 1973 for its U.S. debut and then renamed Honor among Thieves. Twinky was denied a cinema release in the U.S. and went straight to television in 1972. Violent City had to wait until 1973 for a distribution deal, Cold Sweat until 1974 and even Red Sun took nine months before it hit American shores. Until The Valachi Papers did the business, Bronson was not considered the kind of star who could open a picture in the U.S.

By then, of course, Bronson had reversed the normal box office rules. Usually, for films starring American actors, foreign revenues were the icing on the cake. For Bronson it was the other way round. Along with Clint Eastwood he was the first of the global superstars, whose name resonated around the world, and whose pictures made huge amounts of money regardless of American acceptance or interest. But had it been left to Hollywood, Bronson would never have made the grade.

Forgive me for updating this and changing the title. I wrote the first version in 2021 before I came up with the bright idea of tagging as “Behind the Scenes” articles that were not movie reviews. Some of those earlier articles lost out because they lacked that instant identification. This is me making amends.