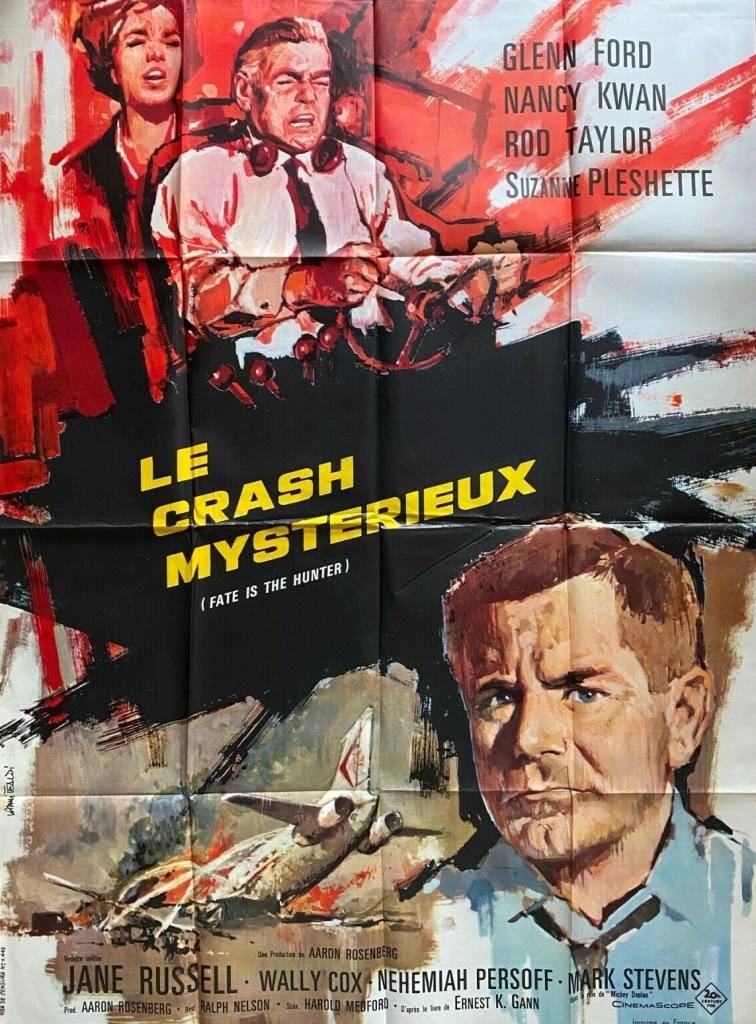

More like Flight from Ashiya (1964) than Flight of the Phoenix (1965) in that airline disaster triggers flashback rather than contemporaneously finding a solution to the problem, but similar in tone to the more recent Flight (2012) and Sully (2016) where the automatic response of the authorities was to blame pilot error rather than ascertain mechanical malfunction. Unlike the two modern pictures, pilot Jack Savage (Rod Taylor) cannot be interrogated in court because he died in the explosion. So investigator Sam McBane (Glenn Ford) seeks some corresponding incident in the past which might account for the pilot making such a mistake.

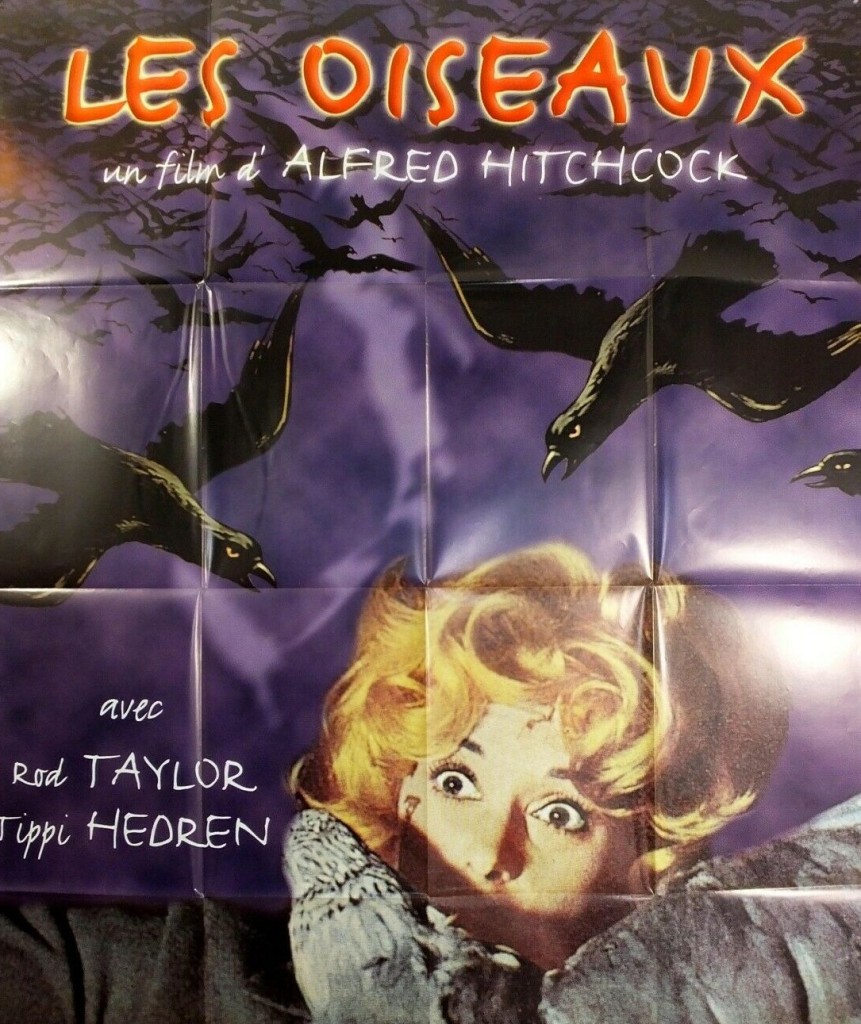

Other options face McBane. Sabotage could be the cause since a passenger took out a $500,000 insurance policy days before boarding the twin-engine plane. Bird strike cannot be ruled out after feathers are found in the engine. Or it could be simple misfortune. Three inbound planes all running late prevent the plane returning immediately to Los Angeles and it would have landed safely on a beach except for hitting a temporary structure. But engineers hardly need to pore over the evidence. The fault is staring them in the face. Savage had reported two engines catching fire but the wreckage reveals one engine intact.

However, the only survivor, stewardess Martha Webster (Suzanne Webster) maintains that two red warning lights were flashing, indicating malfunction in both engines. But since she is badly injured and in a woozy state, this is not taken as gospel. So McBane dips into the playboy past of Savage, a buddy, a man with such appeal he can serenade real-life figures as Jane Russell (playing herself). Two occasions highlight the man’s heroic history of emergency landings. So can he be the unreliable character painted by a jilted fiancée (Dorothy Malone) or the drinker who should not have been in a bar so soon before take-off?

The tight-lipped shoulder-hunched humorless soulless McBane, described as “one of the best-built machines” known to man, finds himself questioning his own attitudes as he uncovers more of his friend’s life. But when it comes to the big enquiry, televised, he has no better an explanation to ascribe the unexpected collision of different events than the “fate” of the title. Naturally, that mystical prognosis hardly goes down well with his superiors. Luckily, McBane comes to his senses and suggests a simulation which does, in fact, pinpoint the flaw.

It’s relatively easy to pinpoint the flaw in the picture. Audiences expecting a disaster movie with characters stranded by a crash were disappointed to find that by cinematic sleight-of –hand they were being presented with The Jack Savage Story, which with the larger-than-life character and his various aviation and romantic adventures would easily have made a picture in its own right. Stuck instead with the glum McBane as their guide, who, beyond his steadfastness, does not come into his own until the last 15 minutes, seemed an unfair trick. The explosion of the doomed plane at the 10-minute mark is easily the dramatic highlight and the continued flashbacks rather than adding to the tension often eased it.

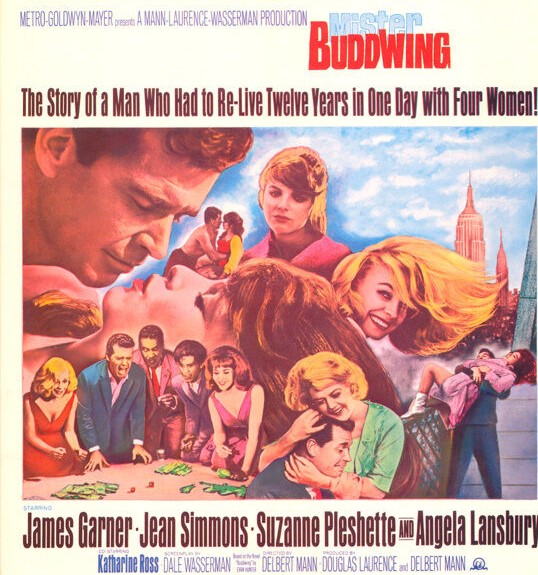

With four stars above the title, audiences might have anticipated some kind of four-sided triangle, but the two female stars scarcely appear although Martha has one excellent scene, shocked when asked to don her uniform again, and Sally (Nancy Kwan) enjoys a fishing meet-cute with Savage.

That said, if you accept as McBane as more of a private eye, his surly demeanor fits, and the Savage life story is certainly a fascinating one and the various aviation episodes unusual enough to maintain interest. Glenn Ford (Is Paris Burning?, 1965), his box office sheen waning and about to shift exclusively to westerns, is always watchable but there’s no real depth to the character. Rod Taylor (Dark of the Sun, 1968) is at his most exuberant and that’s no bad thing, and beneath the bonhomie a good guy at heart, but his portrayal provides little of the shade that would make it thinkable he was to blame. Suzanne Pleshette (The Power, 1968) and Nancy Kwan (Tamahine, 1963) are both under-used. Look out for Mark Stevens (Escape from Hell Island, 1963), Jane Russell (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, 1953) in her first movie in seven years, and Dorothy Malone (The Last Sunset, 1961).

Ralph Nelson (Once a Thief, 1965) sticks to the knitting but four scenes stand out: the explosion, Martha’s breakdown at the sight of her uniform, the stewardess during the simulation staring down the plane at the empty seats filled with sacks of sand, and an excellent composition (which Steven Spielberg pays homage to in West Side Story) of a character being preceded into a scene by his very long shadow. Also worth pointing out is that, in almost James Bond style, the opening sequence lasts ten minutes before there is any sign of the credits.

Harold Medford (The Cape Town Affair, 1967) wrote the screenplay based very loosely on the eponymous bestselling memoir by Ernest K. Gann, whose The High and the Mighty had been turned into a hit picture a decade before. The author was so furious with how much the adaptation veered from his biography – which often pointed out the dangers of flying, recurrent pilot death and airplane unworthiness a main theme – that he took his name off the credits, missing out on an ancillary goldmine as the movie, a box office flop, proved a television staple.