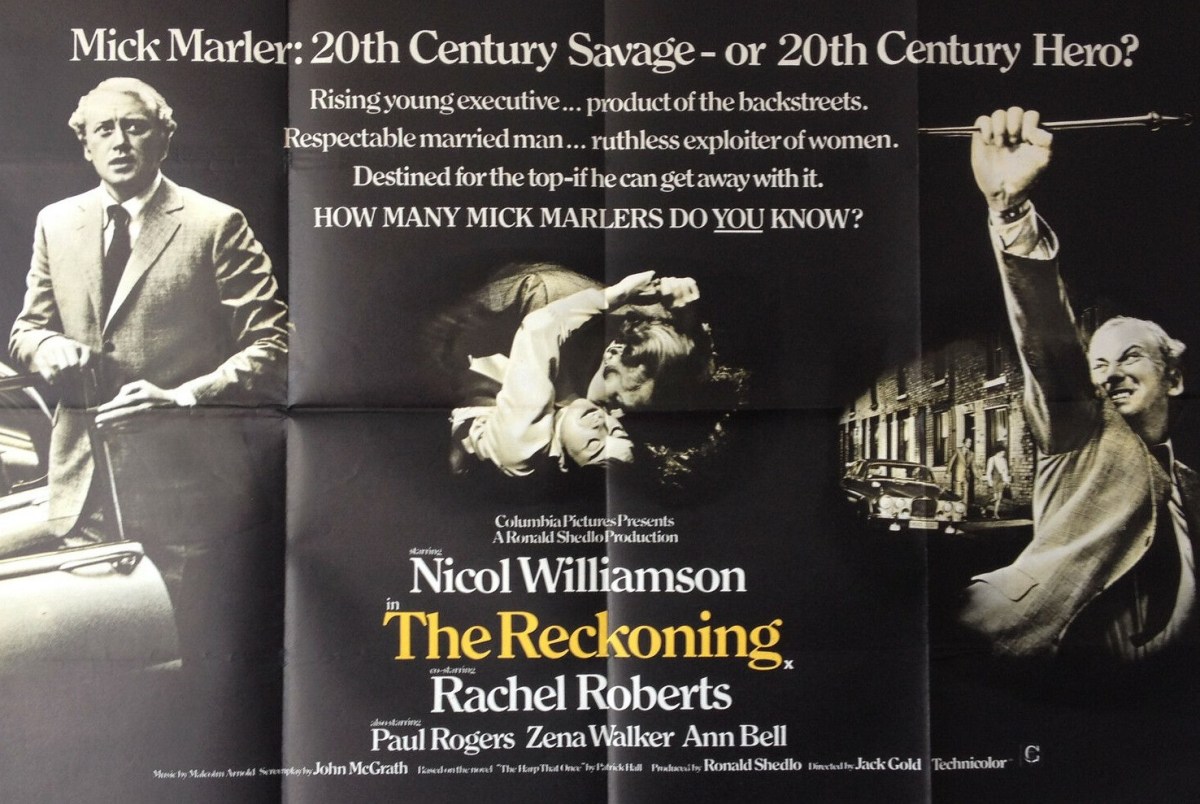

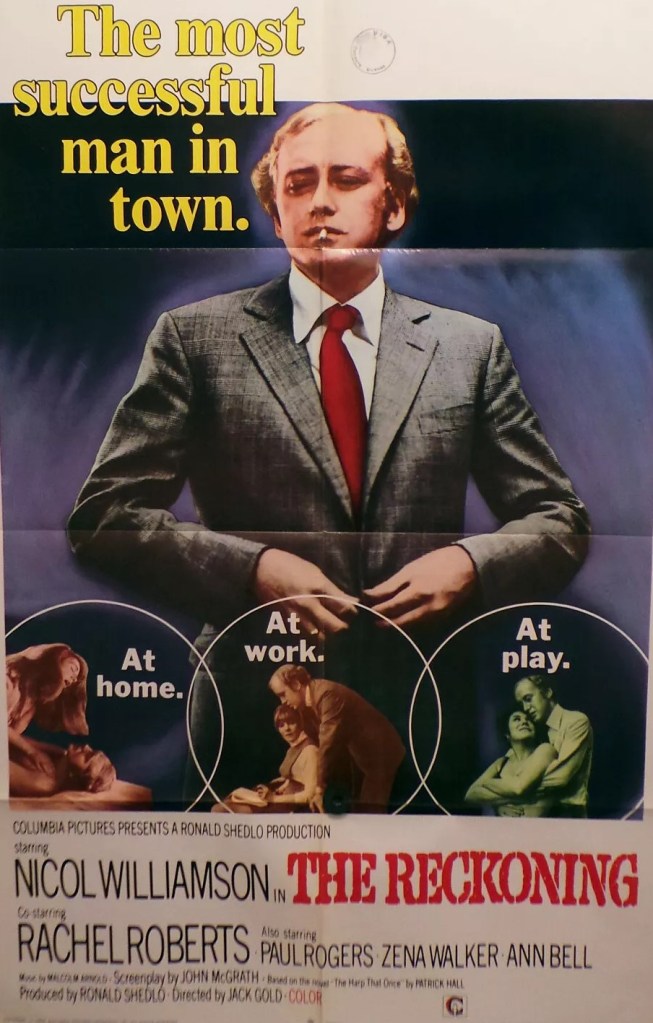

Fans of Succession will love the boardroom battles and fans of Get Carter the gritty violence. Michael Marler (Nicol Williamson) is a thug whichever way you cut it. He’s a business hard-ass, at his nicest he’s obnoxious, at this worst brutal. He drives like a demon. Even in love, he’s fueled by hate, sex with wife Rosemary (Ann Bell) infernal. And all of this made acceptable, according to the left-wing tenets that underwrite the film, because he is a working-class man battling upper-class hypocrisy, never mind that his upper-class wife was hardly foisted upon him, nor that he was forced to live in luxury.

Unexpectedly, the film also explores other themes which have contemporary significance. Computers play a pivotal role and so does honor killing. The picture’s original title – A Matter of Honor – was ironic given that in the upper-class worlds in which he moved, courtesy of his job and marriage, he is considered to have little in the way of chivalry. But in the working-class world he has escaped he must avenge his father’s death in this manner.

The sudden death of his father sends him back to Liverpool where he discovers the old man was killed in a pub brawl. But the local doctor and police, disinterested in complicating what must be a regular occurrence, view his death as accidental. So Marler takes it upon himself to uncover the culprits and wreak revenge, any kind of revenge on any kind of culprit, regardless of the fact that from the outset it is clear they will hardly be gangsters. While contemplating violence, he strikes up a sexual relationship with the married Joyce (Rachel Roberts).

The story jumps between the back-stabbing corporate world to a scarcely less violent working class environment. The combination of charm and brute energy holds a certain appeal for Rosemary (Ann Bell) and helps keep him in the good books of his boss. He is otherwise a bully, targeting the weak spots of anyone who stands in his way on his climb to the top, and while heading up the sales division of a company in trouble blaming everyone else for his own failings. And while scorning his wife’s upper-class friends is quite happy to enjoy the benefits of her lifestyle, the flashy car might be the result of his endeavors but not the huge posh house. Marler stitches up another associate with the assistance of another lover, secretary Hilda (Zena Walker), and his long-suffering wife finally takes umbrage at his venomous manner.

Marler hides his hypocrisy behind the façade of a left-wing class-struggle. John McGrath’s screenplay clearly intends Marler’s working-class background to provide him with a get-out-of-jail-free card as well as to launch an attack on an upper classes seen as namby-pamby except when it comes to putting the poor in their place. The anti-class polemic has somewhat eroded over time but in its place can be found an accurate portrayal of social history. For ordinary people, alcohol, the drug du jour, plays a massive part. The endless terraces, houses without a single car parked outside, the vast pub which hosts wrestling matches and is a tinder spark away from erupting in a brawl, a culture where the first graspings at sex are likely to take place up a close or in a car, are in stark contrast to the high-life Marler enjoys in London.

He has no desire to go back home, hasn’t visited in five years, escaping there deemed a sign of success, and mostly returns metaphorically to draw on memories with which to scourge the upper-class and excuse his own behaviour.

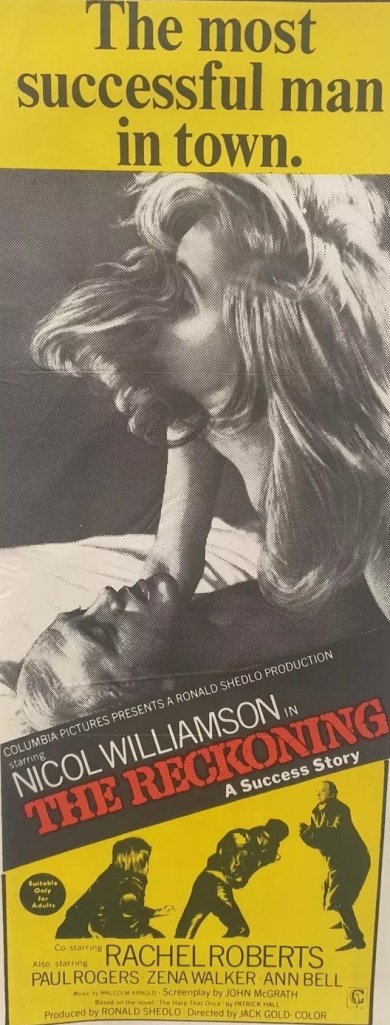

Nicol Williamson (Inadmissable Evidence, 1968) delivers a tour de force, his screen presence never so vibrant, exhibiting the same raw appeal as Caine in Get Carter. At this point in is career, with a critically-acclaimed Hamlet on stage, he was perceived as the natural successor to Laurence Olivier and Columbia held up the release of The Reckoning to allow the Tony Richardson film of the stage production, in which he starred, to pick up critical momentum. Oddly enough Rachel Roberts had not capitalized on her Oscar-nominated role in This Sporting Life (1963) and this was only her second movie in seven years. Initially coming across as brassy, she soon softens into a surprisingly wistful character. Both Ann Bell and Zena Walker bring greater dimension to their characters rather than as adoring doormats. You can catch Paul Rogers (Three Into Two Won’t Go, 1969) and Tom Kempinski in supporting roles.

Director Jack Gold, who had worked with both Williamson and McGrath on his movie debut The Bofors Gun (based on the writer’s play), does a great job of capturing a particular period of British social history as well as Williamson stomping around in his pomp. Written by john McGrath (The Bofors Gun, 1967) and, in his debut, Patrick Hall.

Terrific performance stands up well.