In an ideal world there’d be someone you could complain to if an advertiser stepped out of line. In an ideal world, the agency that won a pitch would be the one that had put in the hard yards researching the marketplace and coming up with the most creative idea rather than the one who took the easy way out by simply wining and dining the client and laying on a bevy of women.

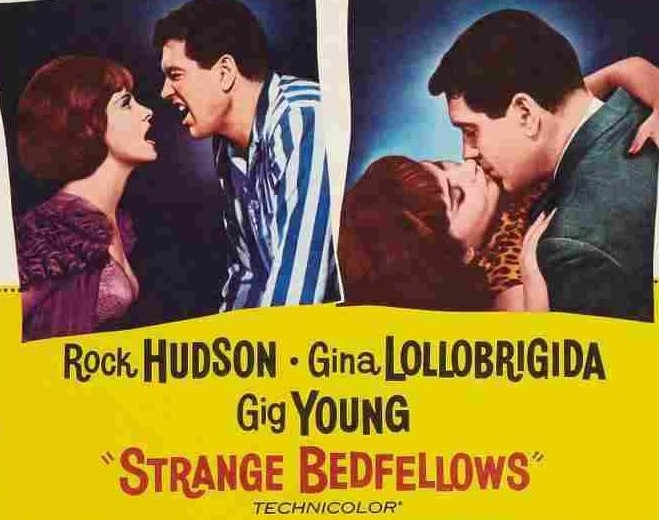

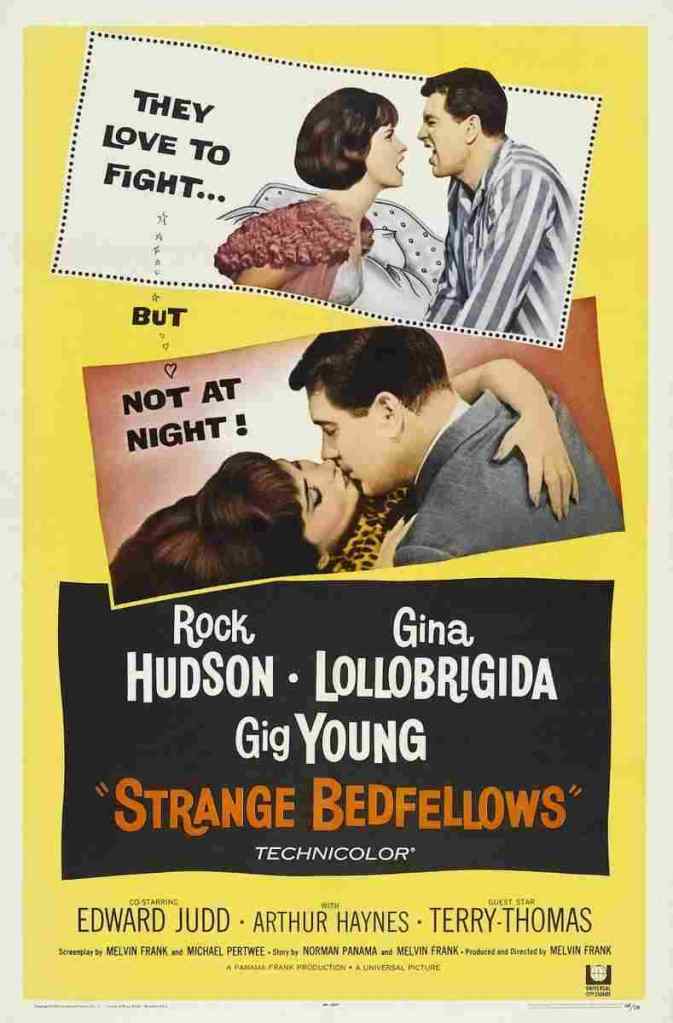

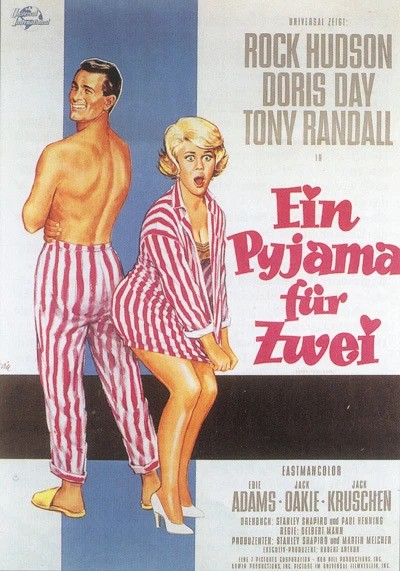

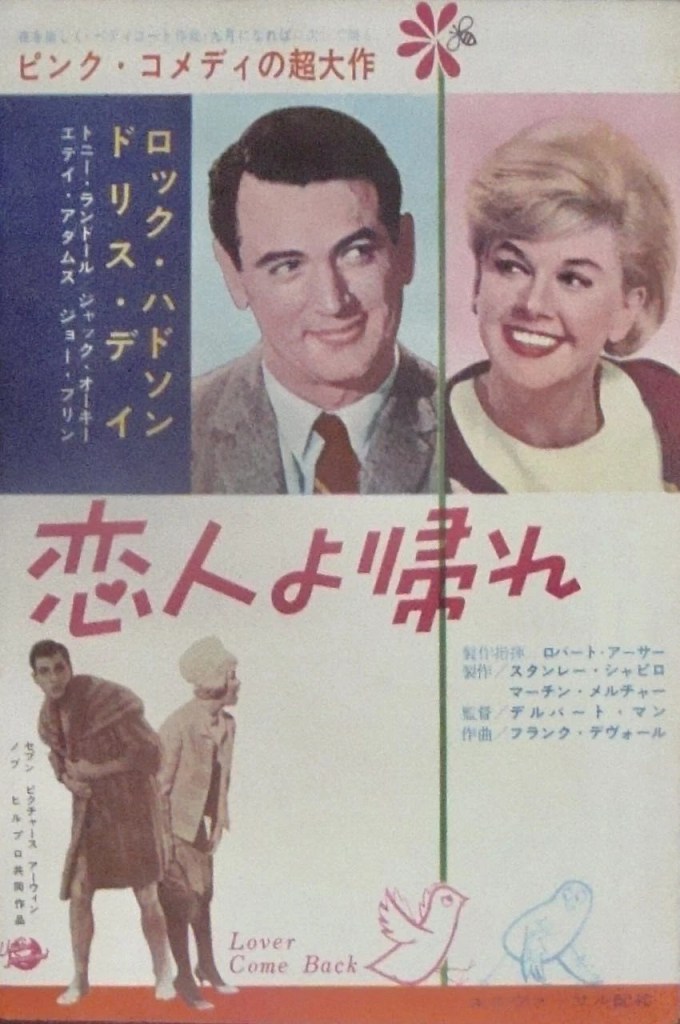

As you might imagine on Madison Ave it will be the prim intense Carol (Doris Day) who will play by the rules and stay up all night honing her pitch. And it would be louche smarmy executive Jerry (Rock Hudson) who puts in the hours but only as far as schmoozing the client and appealing to his primitive nature. Given this is a fiction, I’m assuming the idea of a code of ethics by which advertisers can be brought to book is a figment of the writer’s imagination.

No worries, whether fictional or not, Carol still loses out, Jerry more than capable of winning over the members of the ethics panel by seducing them with seductive chorus girl Rebel (Edie Adams) whom he has promised to turn into a star by featuring her as the model for a new product called VIP.

The only problem is, once Rebel’s usefulness is over, and once the ethics team is satisfied, Jerry has no intention of making such an unlikely candidate for stardom a star. Which is just as well because VIP doesn’t exist. He invented it solely to shoot enough of a commercial to convince Rebel he would honor his part of the deal.

Carol sees through the scam and hauls him up before the ethics board once again. However, Jerry has the sense to bring with him an actual product, a seemingly innocuous candy except it turns out to be highly intoxicating.

Screenwriters had long realized that a drunken Doris Day (The Ballad of Josie, 1967) is a banker and that she’ll use it to hit a comedic home run. And that’s the way it plays out with the complication that the pair have a one-night stand and a subsequent speedy marriage which leads to exactly the kinds of complications you’d expect from a Rock Hudson-Doris Day comedy and with a not unexpected twist at the tail end of the tale.

The only problem here is that we spend so much time satirizing the advertising industry, which, let’s face it, is easy meat, that it takes too long to get to the comedic hard yards the pair eventually put in. Doris Day makes a very persuasive top dog, and with that pinched-up intensity you could easily see her playing such a role in a drama and be very convincing. Generally, when she’s adopting her in-charge mode, there’s plenty inanimate objects to get in the way and create the pratfalls and physical comedy at which she excels. But when she’s just being undone by someone else’s cleverness, she might win sympathy but that doesn’t translate into big laffs.

So it only really gets going when the pair get into a romantic tangle, helped along, as I said by Day’s trademark inebriation. Rock Hudson (Seconds, 1966) is at his best when he’s constantly being taken down a peg or two by a clever woman or is himself ambushed by inanimate objects, so he’s somewhat out of his comfort zone in, here, always sitting in the winner’s circle.

There are certainly some high points but for too long it just drifts along, and much of the sharpness of the satire has been superseded by the more ruthless antics exposed on Mad Men (2007-2015), so it’s lost some of the bite which may have made up for the lack of comedy in the earlier sections.

But there’s no diminishing the screen charisma of the Hudson-Day partnership. It brought out the best in both actors. Tony Randall (Bang! Bang! You’re Dead! / Our Man in Marrakesh, 1966) puts in an interesting shift as Jerry’s boss who is bullied by his underling. Edie Adams (The Honey Pot, 1967) adds scheming to sultriness.

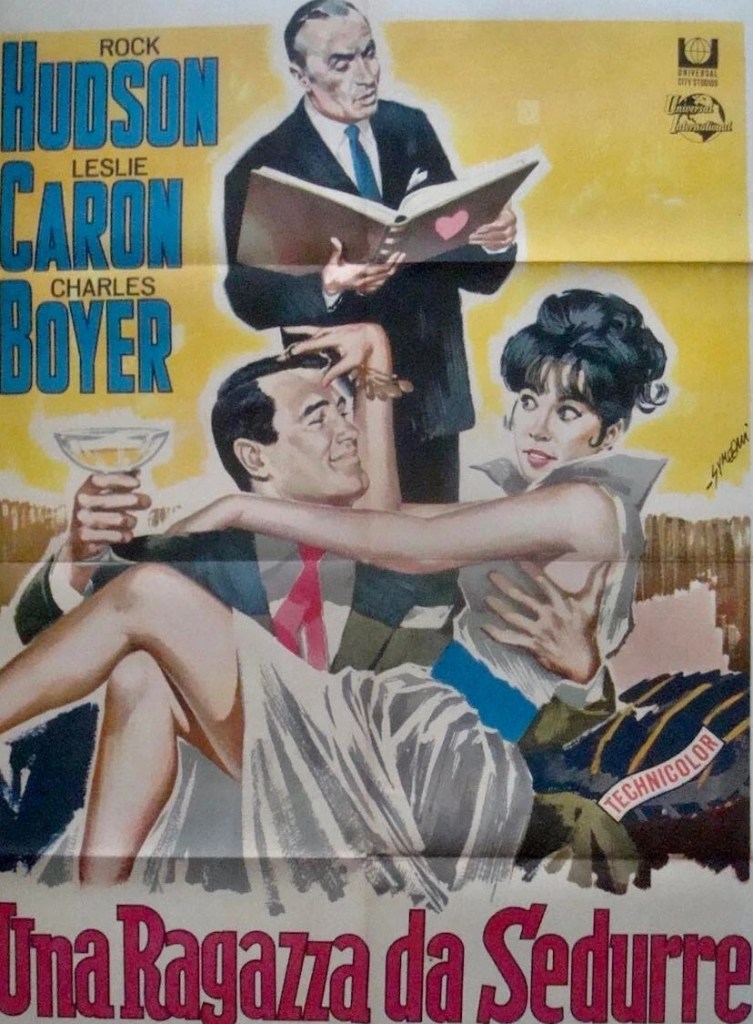

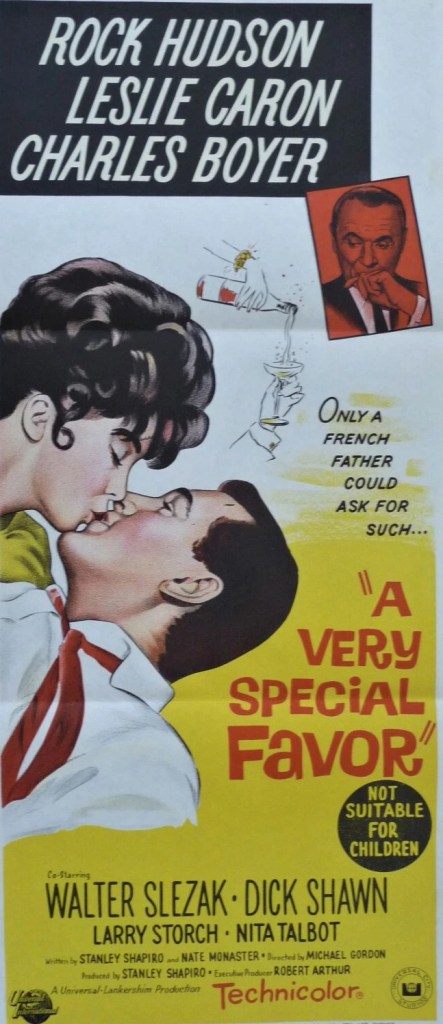

Directed by Delbert Mann (Buddwing, Mister Buddwing, 1966) from a screenplay by Stanley Shapiro (A Very Special Favor, 1965) and Paul Henning (Bedtime Story, 1964).

Good wholesome fluff.