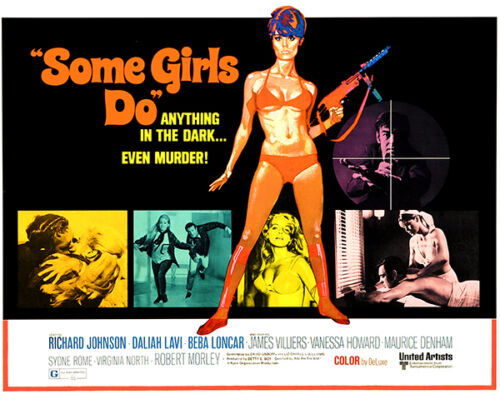

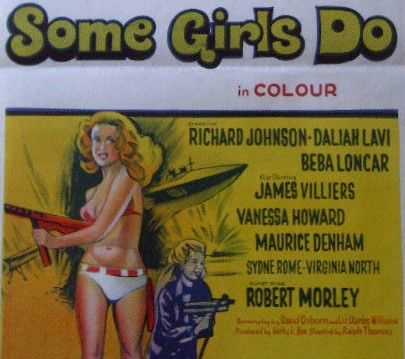

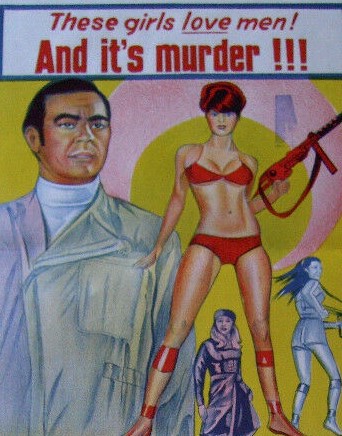

Enjoyed this sequel to Deadlier Than the Male (1967) far more than I expected because it sits in its own little world at some point removed from the espionage shenanigans that dominated the decade. Hugh (nee Bulldog) Drummond is neither secret agent nor involved in espionage high jinks, instead employed in the more down-to-earth domain of insurance investigator, albeit where millions are at stake. Although his overall adversary is male, the smooth-talking Carl Petersen (James Villiers), adopting a series of disguises for most of this picture, the real threat comes from a pair of villainesses in the shape of Helga (Daliah Lavi) and Pandora (Beba Loncar – the latter, yes, having her own deadly Box. If anything, this pair are a shade more sadistic than Irma and Penelope from the previous outing.

The sequel doubles up – or doubles down – on the female villainy quotient, Petersen having created a race of lethal female robots who spend their time dispatching scientists working on the world’s first supersonic airliner. Global domination is only partly Petersen’s aim since he also stands to gain £8 million ($134 million today) if the plane doesn’t launch on schedule. Livening up proceedings are Flicky (Sydne Rome), a somewhat kooky Drummond fan who has her own agenda, Peregrine “Butch” Carruthers (Ronnie Stevens), a mild-mannered embassy official assigned bodyguard duties, and chef-cum-informant Miss Mary (Robert Morley).

Villiers has found a way of turning an ultrasound device intended originally to aid cheating in a boat race into something far more dangerous. But, of course, for Helga seduction is the main weapon in her armoury, and Drummond’s first sighting of her – a superb cinematic moment – is sitting on the branch of a tree wielding a shotgun. Equally inviting are the squadron of gun-toting mini-skirted lasses guarding Petersen’s rocky fortress.

The movie switches between Helga, Pandora and the robots raining down destruction and Drummond trying to prevent it. Dispensing with the boardroom activities that held up the action in Deadlier than the Male, this is a faster-moving adventure, with Drummond occasionally outwitted by Helga and calling on his own repertoire of tricks. Dialogue is often sharp with Drummond imparting swift repartee.

The action – on land, sea and air – is a vast improvement on the original. The pick is a motorboat duel, followed closely by Drummond in a glider coming up against a venomous aeroplane and saddled with a defective parachute. And there are the requisite fisticuffs. Various malfunctioning robots supply snippets of humour.

Richard Johnson (A Twist of Sand, 1968) truly found his metier in this character and it was a shame this proved to be the last of the series. Although Daliah Lavi never found a dramatic role to equal her turns in The Demon (1963) and The Whip and the Body (1963) and had graced many an indifferent spy picture as well as The Silencers (1966), she is given better opportunity here to show off her talent. Beba Loncar (Cover Girl, 1968) is her make-up obsessed bitchy buddy. Sydne Rome (What?, 1972) makes an alluring her debut. James Villiers (The Touchables, 1968) is the only weak link, lacking the inherent menace of predecessor Nigel Green.

There’s a great supporting cast. Apart from Robert Morley (Genghis Khan, 1965) look out for Maurice Denham (Danger Route, 1967), Adrienne Posta (To Sir, with Love, 1967) and in her first movie in over a decade Florence Desmond (Three Came Home, 1950). The robotic contingent includes Yutte Stensgaard (Lust for a Vampire, 1971), Virginia North (Deadlier Than the Male), Marga Roche (Man in a Suitcase, 1968), Shakira Caine (wife of Sir Michael), Joanna Lumley (television series Absolutely Fabulous), Maria Aitken also making her debut, twins Dora and Doris Graham and Olga Linden (The Love Factor, 1969). Peer closely and you might spot Coronation Street veteran Johnny Briggs.

The whole package is put together with some style by British veteran Ralph Thomas (Deadlier than the Male).

CATCH-UP: Chart through the Blog how Richard Johnson’s career went from supporting player to star via The Pumpkin Eater (1964), Operation Crossbow (1965), Khartoum (1965) Deadlier than the Male (1967), Danger Route (1967) and A Twist of Sand (1968). Conversely, see how Daliah Lavi went from European star of The Demon (1963) and The Whip and the Body (1963) to Hollywood supporting player in Lord Jim (1965).

Network has this on DVD currently at a bargain price in a double bill with Deadlier Than the Male.

And you can also catch Some Girls Do on YouTube.