There were five our great reasons to see this picture. Firstly, it was in Cinerama. Secondly, it was the first attempt in that special format to tell a dramatic story rather than offer just a travelog. Though How the West Was Won (1962) was promoted at the first dramatic use of Cinerama, that was actually untrue. This came first. Third, there was a terrific gimmick – Smell-O-Vision – which allowed audiences to inhale around 30 fragrances at the same time as the onscreen characters. Fourthly, it was produced by Mike Todd Jr., son of the Oscar-winning producer of Around the World in 80 Days (1956) and second husband of Elizabeth Taylor who was instrumental in bringing Cinerama to the big screen in the first place., Lastly, it was the first top-billed appearance of rising British star Denholm Elliott.

Unfortunately, none of these hit the target and it remains a novelty in the Cinerama canon. For a start, there wasn’t much of a story – it’s a chase tale of sorts with crime novelist Oliver (Denholm Elliott) uncovering a plan to kill American heiress Sally Kennedy. In setting out to thwart it he travels all over Spain in the company of philosophic wise-cracking taxi driver Smiley (Peter Lorre). Cue travelog of scenic Spain including fiestas, dances and the running of the bulls, which appears not to have been specially staged but filmed documentary-style as it occurred with the bulls inflicting considerable damage on the humans foolish enough to think it’s a lark.

The hook is the mystery woman who can only be detected by her Schiaparelli perfume while the giveaway for the villain, hired assassin Baron saradin (Paul Lukas), is his tobacco. Cue an onslaught of scents. But the smells don’t just pop up when characters are involved. When a barrel of wine smashes, that produces another smell.

Astonishingly, the movie manages to bring in some of the Cinerama trademarks – the runaway element seen from the audience POV, not just the traditional vehicle but also barrels of wine.

The smell gimmick worked well enough in cinemas set up for such technical aspects, but that amounted to very few screens, and outside of those the movie just seemed a random series of scenes with only panoramic views of Spain to lessen the boredom.

It did nothing for the career of Denholm Elliott and he did little for the movie. He lacked the edge or innocence required to make such a character come alive and mostly he looks as though he doesn’t know what to do. He didn’t make another movie for three years and on his return for Station Six Sahara (1963) he was no longer the star but quickly shifting into the character actor he would be for the rest of his screen career.

It was nearly the last hurrah for Peter Lorre. He suffered heart attack during filming so the real Peter Lorre is only seen in half the picture, for the other half it’s a stand-in.

The presence of Elizabeth Taylor (Butterfield 8, 1960) could conceivably have redeemed the picture but she puts in only a fleeting appearance, so speedy her distinctive features barely register. You see more of Diana Dors (Baby Love, 1969).

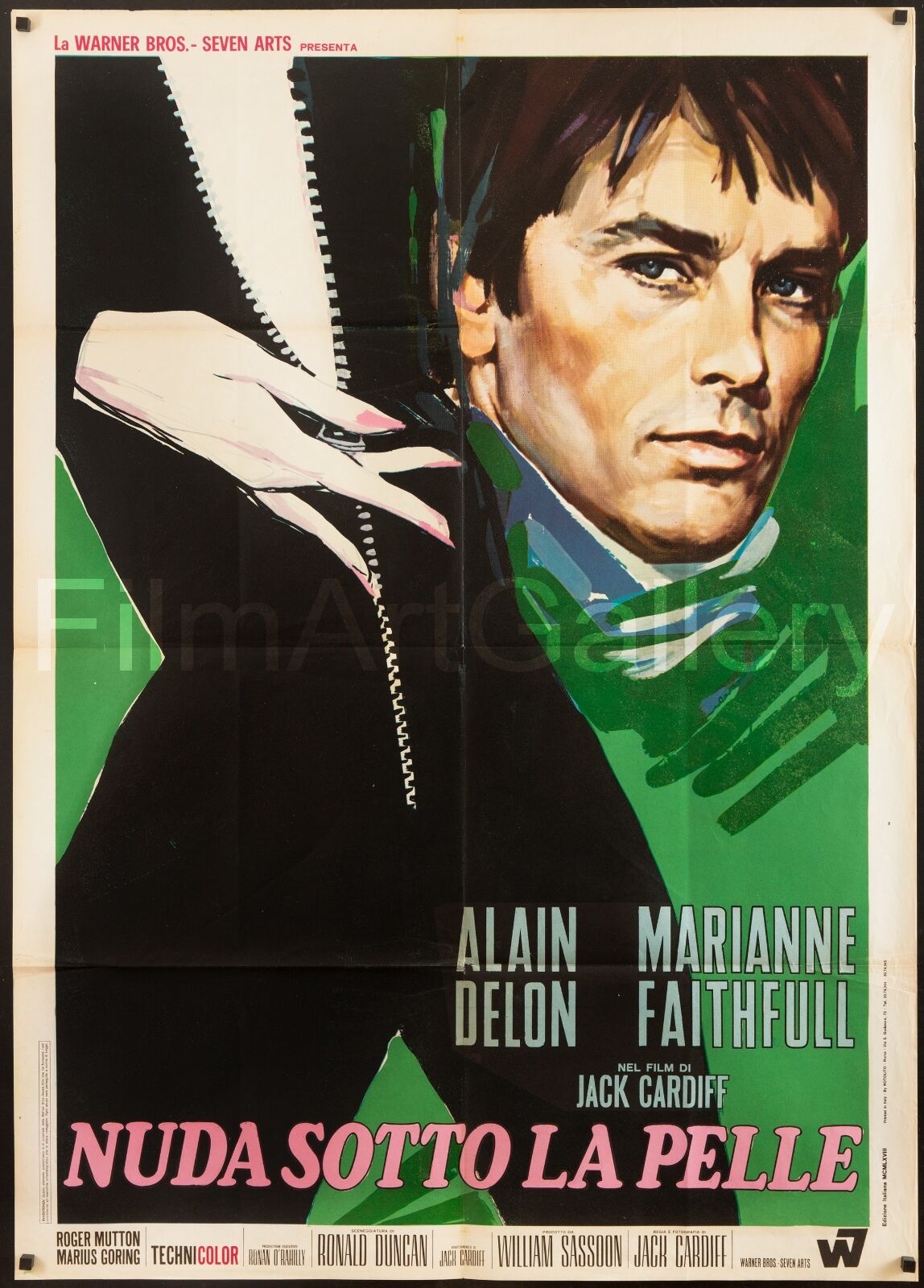

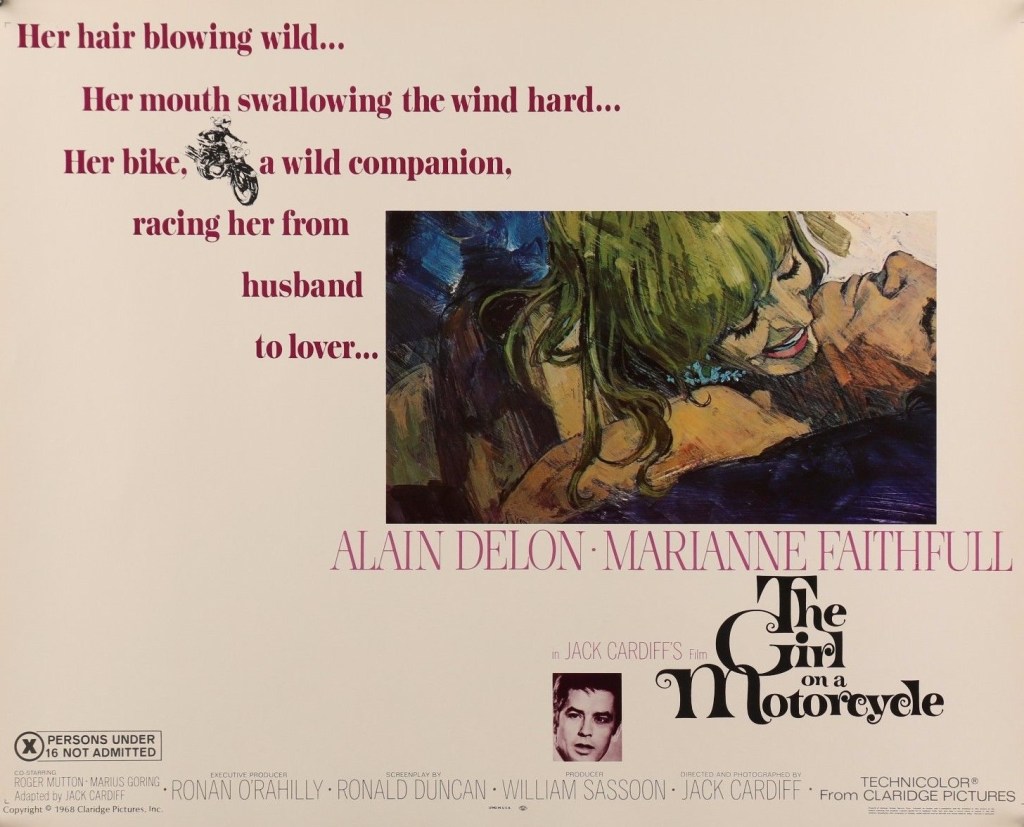

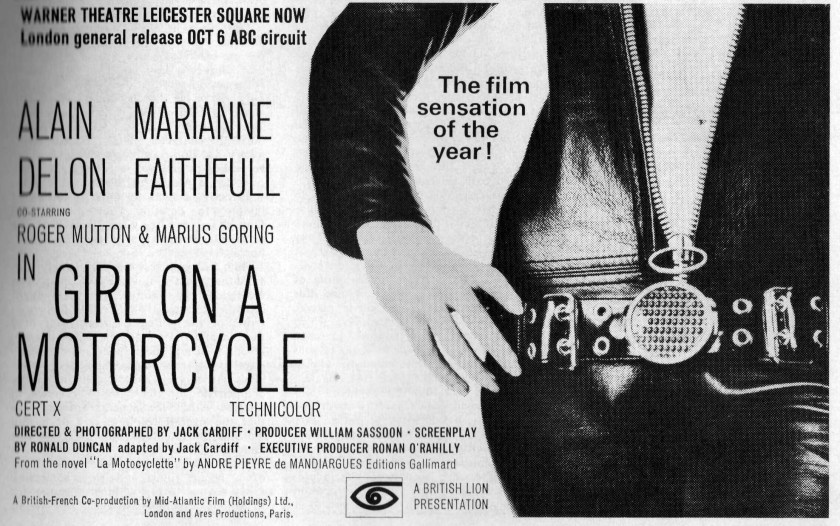

In the hands of Alfred Hitchcock (Psycho, 1960) or imitators like Stanley Donen (Charade, 1963) and with a more finely worked screenplay, reliant on neither visual nor olfactory gimmick, this might have worked. But it was in hands of Jack Cardiff (The Girl on a Motorcycle, 1968), famed cinematographer but only his third outing as a director, and he clearly didn’t know how to balance the various ingredients and so it limps home.

The minute the location of the source novel by Audrey Kelley and William Roos shifted from New York to Spain and the number of investigators halved, the trouble started. The hunt for a woman whose existence is in question was a standard mystery trope and might very well have worked here minus the smells and Cinerama.

A curiosity.