Television hadn’t produced the goods in terms of furnishing Hollywood with an abundance of new talent. We were still only talking about Steve McQueen (Bullitt, 1968) and James Garner (Buddwing/Mister Buddwing, 1966) in the 1960s as having made a successful transition from small-screen to big-screen stardom with occasional brief flurries from the likes of Clint Walker (The Dirty Dozen, 1967). Though Hollywood kept trying – Universal had tossed thirty-two of its contracted players into Airport (1970) in the hope one would catch audience attention.

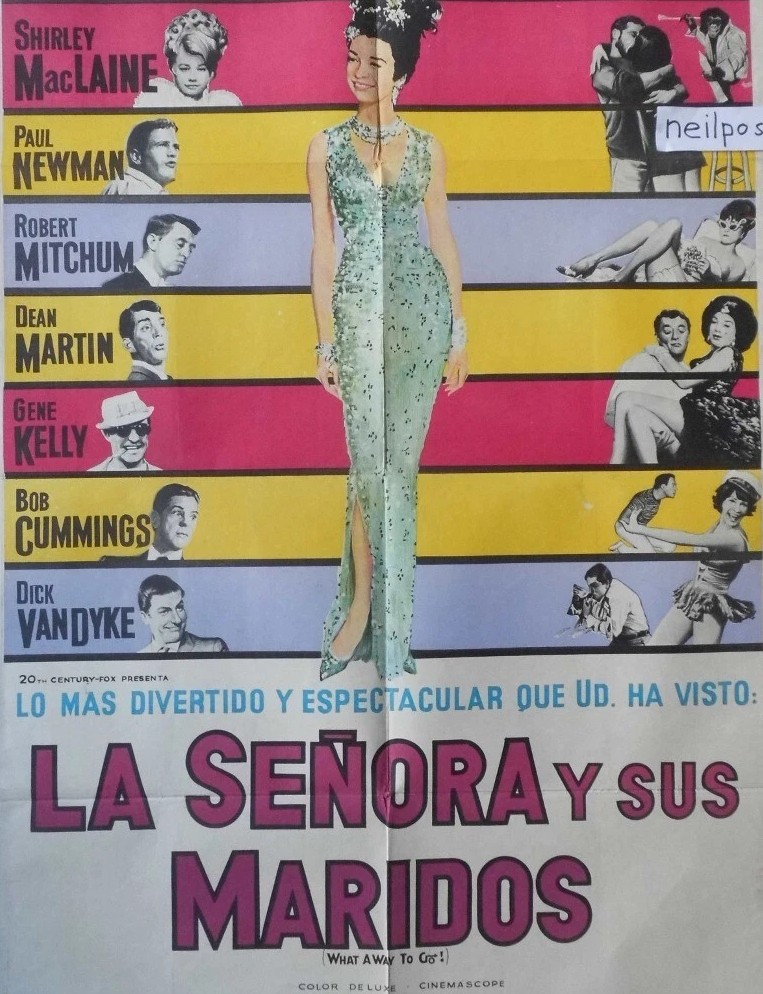

But it turned out Hollywood had been looking in the wrong direction. Expecting to unearth actors who could carry dramas or thrillers or westerns, Hollywood had, in general, not considered comedy as a source of new talent. Dick Van Dyke (Chitty, Chitty, Bang, Bang, 1968) was considered an anomaly because he could morph into a song-and-dance man and his comedy was based on the physical.

So the industry was astonished when Goldie Hawn emerged from what was essentially a comedy skit show, The Rowan and Martin Laugh-In, to become a genuine screen box office comedienne and over the next decades there would be an excellent harvest from television comedy including Robin Williams, Chevy Chase and a whole troupe of others.

But it’s a shame that Goldie Hawn got all the glory – she won an Oscar – because this was the picture that established Walter Matthau as a genuine star as opposed to part of a double act with Jack Lemmon (The Fortune Cookie, 1966, and The Odd Couple, 1968). John Wayne once made the point that most acting is actually reacting to what someone else has said and in that regard there’s a masterclass from Ingrid Bergman (The Visit, 1964), playing determinedly against type.

Deceit drives the narrative. Just like Dean Martin in Airport (1970), upscale dentist Dr Julian Winston (Walter Matthau) has cottoned onto the fact that he can keep marital interest from mistress Toni (Goldie Hawn) at bay by the fact that he’s married. Except he isn’t and has to rustle up a fake wife to keep Toni on the hook. So he turns to spinster nurse Stephanie (Ingrid Bergman), a Swede cut from the repressed Bergmanesque cloth rather than the free loving spirit of popular (male) imagination, who has been carrying a torch for him for years, so, despite the notion that it’s not real, she goes full-tilt-boogie into the pretense. She’s even got a couple of nephews in tow who can masquerade, unknowingly, as Winston’s own kids.

Meanwhile, Winston rethinks his position, realizes he doesn’t want to lose Toni and reckons the only way he can get himself out of the sticky situation of his own creation is to pretend that his imaginary wife is also having an affair, so he has to set Stephanie up on dates with some of his customers so Toni can get a peek at them.

Assuming from its stage origins – France before being adapted for Broadway – this had more farce in the original production, that aspect has been trimmed back to concentrate on the various degrees of deceit. Instead of trying to force laffs from opening and closing doors and men being caught with their trousers down, this follows the simpler plotline of maintaining the deceits while inserting a potential twist when Toni develops an interest in her neighbor, author Igor (Rick Lenz).

The three principals are excellent, all bringing something fresh to the table, Walter Matthau as a lothario rather than a crafty conniver a distinct change of pace, Goldie Hawn a refreshing new face who was soon able to carry pictures on her own, and, especially, to my mind Ingrid Bergman. She has two absolutely marvelous reactions to information received – in the first her elbow literally falls from a table, in the second she is overwhelmed at the thought of receiving a gift, and she has the best scene of all, cutting loose on the dance floor.

As you might expect, the romantic entanglements are resolved.

Director Gene Saks (A Thousand Clowns, 1965) sticks to the knitting, extracting weighted performances from the cast without resorting to insipid extras. I.A.L. Diamond (The Fortune Cookie) adapted the Broadway play by Abe Burrows (Can-Can, 1960) who in turn had borrowed the French play by Pierre Barillet and Jean-Pierre Gredy.

Most 1960s comedies have lost their verve but this still plays exquisitely.