Only in Hollywood could you come off three straight flops and be offered for your next picture your biggest-ever salary. But producer Elliott Kastner in his attempt to break into the big time was following the game plan of United Artists when they had set out the previous decade to woo the biggest stars with big deals – and the same format that Cannon followed two decades later to sign up the likes of Sylvester Stallone.

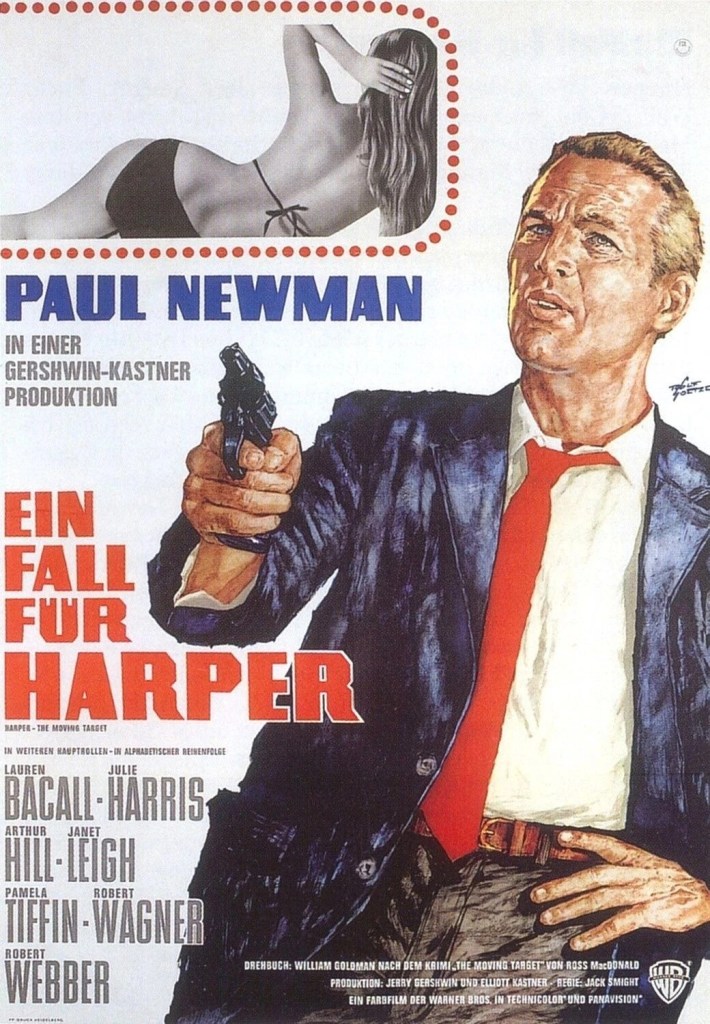

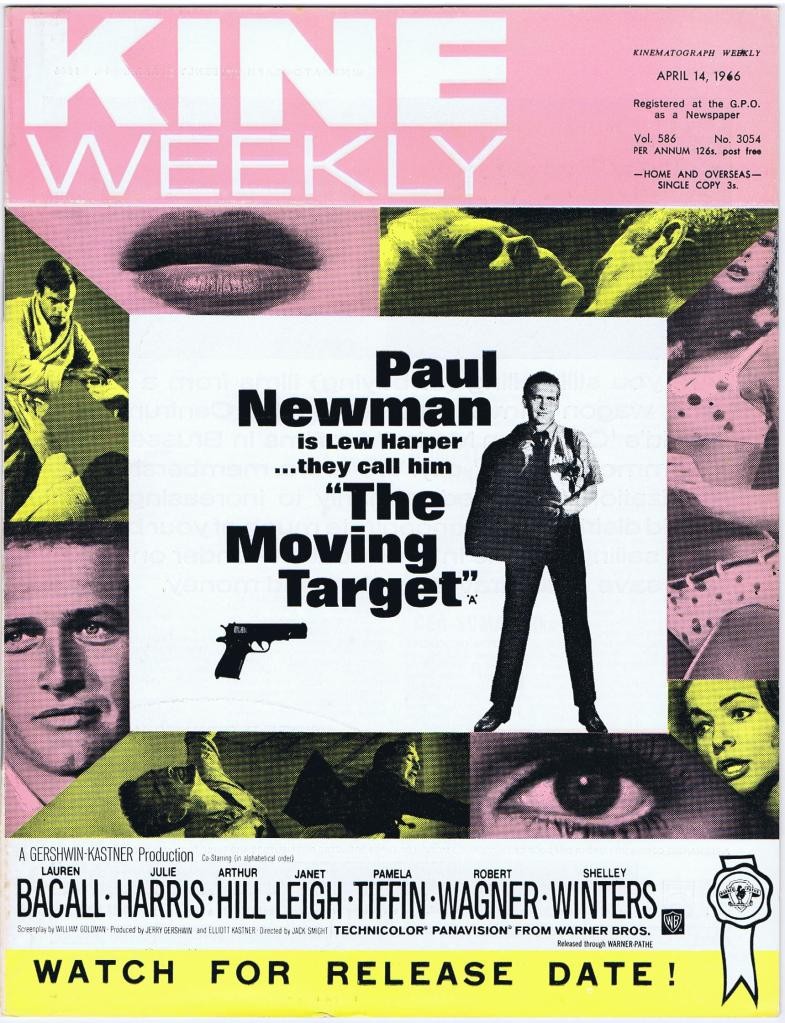

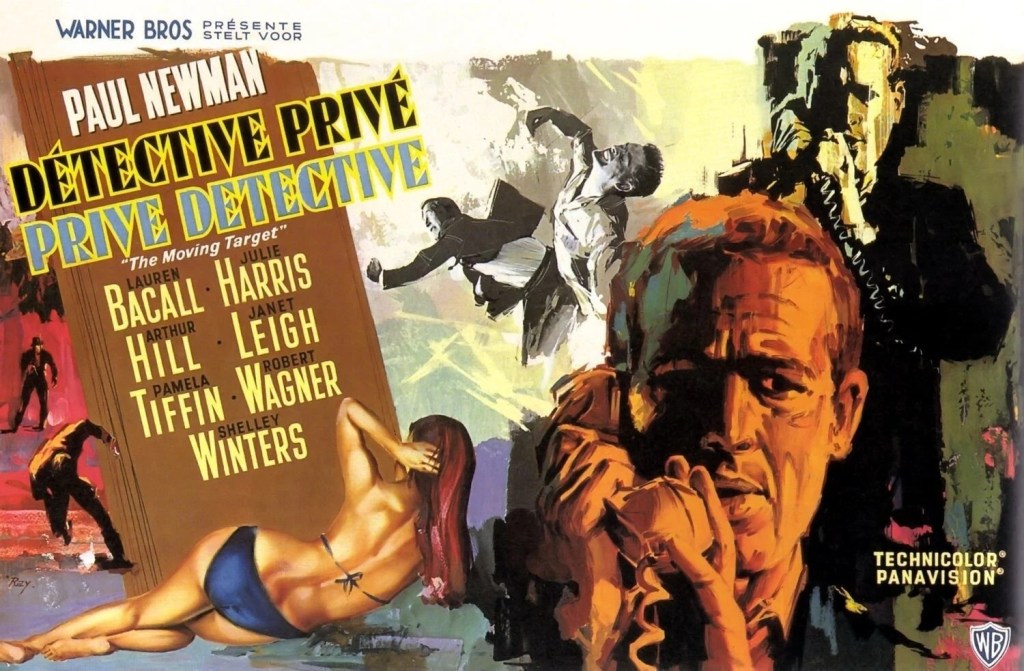

Paul Newman received $750,000 – matching the fees of John Wayne – plus 10% of the profits for his role in Archer. The original title was the surname of the private eye in Ross MacDonald’s The Moving Target. The novel’s title was in play for some time before being superseded by Harper (though it remained The Moving Target in the UK) on the basis that characters whose name began with “H” – namely Hud (1963)and The Hustler (1961) – had done well for the actor in the past.

Harper was the first project in a five-picture deal between Elliott Kastner (along with producing partner Jerry Gershwin) and Warner Brothers. This was to be followed by heist thriller Kaleidoscope (1966) starring Warren Beatty, Peter Sellers comedy The Bobo (1966), drama Sweet November (1969) and Harper sequel The Chill, reprising Newman.

The actor had thrown away the box office cachet he had achieved earlier in the decade with such pictures as Exodus (1960), The Hustler (1961) and Hud (1963) on a trio of losers – What a Way to Go (1964), western The Outrage (1965) and Lady L (1965). But that didn’t deter former talent agent Kastner.

Although Kastner only had one picture to his name, Bus Riley’s Back in Town (1965), top-billing Ann-Margret, it wasn’t for lack of trying. He had first made a splash in 1962 when he and screenwriter Abby Mann bought William Faulkner’s Light in August for $150,000. But that failed to get past the starting gate, as did The Crows of Edwina Hill based on the novel by Allan Bosworth, The Children of Sanchez to be directed by Vittorio De Sica, Honeybear, I Love You to star Warren Beatty – an original screenplay by Charles Eastman (Little Fauss and Big Halsy, 1970) – and an adaptation of William Goldman’s bestseller Boys and Girls Together.

When Kastner set up in business with Jerry Gershwin in 1965, he had ten projects on the go, having spent $538,000 buying the rights to three plays and five novels plus commissioning two original screenplays.

It was amazing that the movie was made at Warner Brothers because several years earlier studio and star had a major falling-out, the actor suing to be released from his long-term contract, eventually buying his way out for a considerable sum.

As Kastner couldn’t afford the rights to any of the books published by his idols Raymond Chandler or Dashiel Hammett he plumped for the “lesser known” Ross MacDonald “who had the same rhythm.” Since MacDonald’s agent Harold Swanson didn’t want to sell the rights to the character, Kastner agreed to switch the name from Archer to Harper. And as Kastner “couldn’t afford a real screenwriter,” he hired William Goldman, who had authored three books the producer admired. He paid Goldman $80,000 to write “a movie with balls” based on the first novel in the Lew Archer series, requiring some updating since it was published in 1949.

Private eyes were now the preserve of television, which was rife with them, so it was going against the grain to try to reinvent the genre. Frank Sinatra, coming off the hit Von Ryan’s Express (1965), expressed interest in the project.

“I always knew that if you wanted to get money for a big studio picture you needed Gregory Peck, Burt Lancaster or Paul Newman,” Kastner wrote in his memoirs. He decided Newman was the best choice and travelled to Scarborough, a holiday resort on the north east coast of England, where Newman was shooting Lady L with Sophia Loren. “With no proper sleep or proper food,” Kastner found out the movie’s location and “wasted no time going up to Newman’s trailer and knocking on the door.” He had never met Newman, so was “a bit scared.” For a moment it looked like he was going to get the brush-off, but when he mentioned the actor playing a private eye that caught Newman’s attention. He read the script in a day and agreed to do it.

Newman’s agents Freddie Fields, David Begelman and John Foreman (who, all, coincidentally, later became producers) were unhappy that Kastner had, to all intents and purposes, gone behind their back. However, Newman had confirmed he wanted to make the picture so all that was left for his agents was to negotiate the fee and points. Being agents, and wanting a share of anything else that was going, they recommended another client, Elliott Silverstein, hot after Cat Ballou (1965) as director. Silverstein apparently loved the script although Kastner discovered that Newman had once turned Silverstein down for a job.

Over dinner with Newman and the director in London, Kastner found out Silverstein actually hated the script. He badmouthed the screenplay. “All he wanted to do was spit in Paul Newman’s face.” Next day, Kastner had to pick Newman up from the proverbial floor and regain his trust. The actor was partly mollified by the fact that Kastner had signed up a stronger-than-usual supporting cast in the likes of Julie Harris and Lauren Bacall. “To his everlasting credit, he agreed.”

Now Kastner had to find a studio to back the project. Which he reckoned would not be hard. “If you had Gregory Peck or Paul Newman all you needed was the Burbank telephone directory to make the deal. Despite the “disastrous” end of Newman’s relationship with Warner Brothers, Kastner found no opposition from studio chief Jack Warner, whom he knew from his agent days. “He kinda liked me, so I went to see him first.” Prior to the meeting, he had sent screenplay, book, budget, cross plot and schedule. Ben Kamelson took the meeting with Jack Warner and Elliott Kastner. “He (Jack) was overly friendly and warm and kept on telling Kamelson that I was his boy and that he was so happy to have Paul Newman back on the lot.”

His attitude changed at the mention of Kastner’s fee – $500,000 and half share of the profits. “He went apoplectic. The going rate for producers at WB was $35,000, even a top producer like Sam Spiegel would not, in Jack’s eyes, merit more than $125,000.”

It was a deal buster. But just as Warner was about to kick him out of the office, Kastner rallied. He told the head honcho, “I paid for the acquisition of the book. I paid the writer for the screenplay. I paid for all the expenses back and forth to Europe, twice with a director as well. You say you are happy with the screenplay – it reminds you of The Maltese Falcon. You are sanguine about the overall budget, so why do you begrudge what you are paying to me since I never asked for a dime in the high risk area of development and not only that I capture a genuine movie star. Now listen to me I am gonna go across the hill to Fox and you know what Zanuck’s gonna do? He is gonna lock the door and not let me out until I sign the agreement. I came to you first because I like you so much.”

Warner quickly reconsidered and greenlit the picture.

For director, Kastner went for Jack Smight, “a knowledgeable mechanic and a skilful director” who liked the script. The star asked for changes to the script, including swapping the character’s original beat-up Ford for a snazzy Porsche. Newman “simply shouldered the script and rammed it home” assisted by the fact that he “didn’t have to do a lot of work” since in real-life he resembled the character. Despite her proven acting qualities, there was no doubt that the name of Lauren Bacall in the cast, who had made her name on The Big Sleep (1946) opposite Humphrey Bogart whom she later married, helped generate awareness.

The movie was budgeted at $3 million including Newman’s fee and $500,000 for the producer.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. WB Head of Production Walter Macqueit objected to using Conrad Hall as director of photography on the grounds of his inexperience with color. Kastner held his ground. The bulk of the rest of the crew came from the Warner lot. Kastner worked with Smight on the “meticulous casting.”

The movie was filmed entirely in Los Angeles with exteriors in Burbank and interiors at the WB studio. During production, Kastner was also planning his next move, which was to quit Hollywood and set up a production shingle in London with Jerry Gershwin.

The only niggle at the end of a very successful project was that after Kastner introduced William Goldman to Paul Newman when the writer came up with a spec script for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) he didn’t pass it on to the producer who had given him his big break.

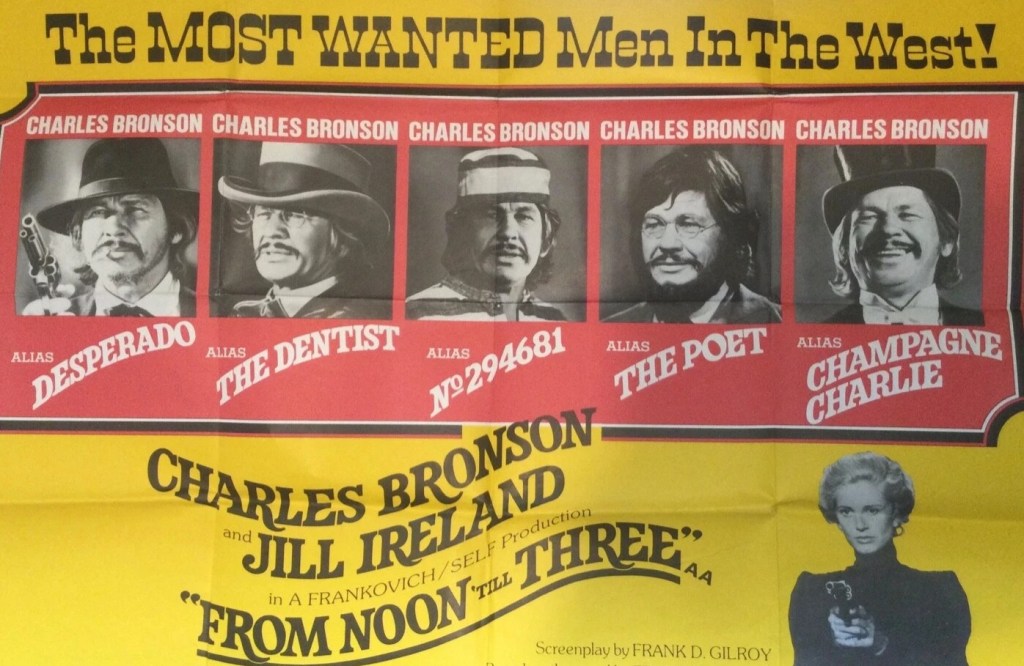

Paul Newman quickly dropped out of the sequel and the project shifted from Warner Brothers to the newly-formed Commonwealth United with Sam Peckinpah set to direct. But The Chill, a more recent book in the series, published in 1964, never came together though later Newman signed up for The Drowning Pool, the second in the Archer series

SOURCES: Elliott Kastner’s Unpublished Memoirs, courtesy of Dillon Kastner; Daniel O’Brien, Paul Newman, (Faber and Faber, 2004), p115-118; “Kastner-Mann Shoot Faulkner’s August,” Variety, May 2, 1962, p5; “Elliott Kastner on Honeybear,” Variety, January 23, 1963, p4; “Elliott Kastner Will Helm Crows,” Variety, May 1, 1963, p21; “WB Partner and Star of Goldman Tale, Variety, March 31, 1965, p7; “Radical Kastner-Gershwin Policy,” Variety, May 19, 1965, p19; “Gershwin-Kastner,” Variety, November 30, 1966, p11; Gershwin-Kastner Set Chill of CU,” Variety, October 15, 1969, p7.