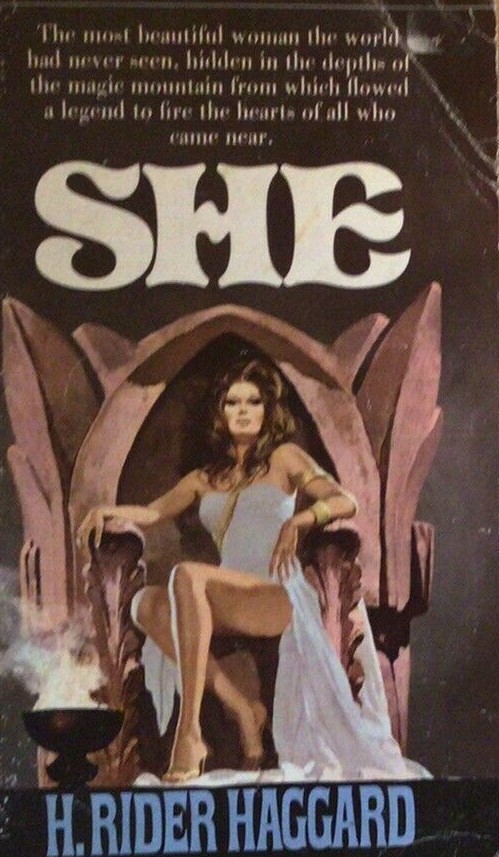

Hammer made a substantial number of changes for its version of She. For a start, H. Rider Haggard’s novel was published in 1886, three decades before the time in which the film which took place at the end of World War One. While the three main characters – Horace Holly (Peter Cushing in the film), his manservant Job (Bernard Cribbins) and the younger Leo (John Richardson) – remain the same, their relationships are significantly different, in that in the book Holly is the legal guardian of Leo.

The book is far more Indiana Jones than sheer adventure, the journey into the unknown instigated by a piece of parchment and a translation of a potsherd from the fourth century B.C. In the film the spur towards the journey into the unknown is a vision. But in the book the adventurers already know before they set off that ancient Egyptian high priest Kallikrates found Ayesha and the sacred flame and was killed by her because he loved another.

Unlike the film the book has no trek through the desert either which renders them hungry, thirsty and exhausted and leads to visions of Ayesha for Leo. Instead, they are shipwrecked. And their peril comes from swamps and wild animals such as lions and crocodiles. In fact, the filmmakers clearly resisted the opportunity to include one of the tropes of jungle adventure, namely a wild animal battle, in this case crocodile vs. lion, which was a feature of the book.

While they shoot a water buck for food, nonetheless they do later face exhaustion, only rescued by the sudden appearance of an Arab, who mentions She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed and arranges for them to be transported in litters to a mysterious land in the heart of African darkness. This land is rich and fertile, with herds and plenty of food.

Two important elements introduced here shape the book but are ignored in the film. The first is that Leo, seriously ill at this point – and not capable of being strung up for the movie’s sacrifice – remains ill for the rest of the book so that it is Holly who enjoys most of the encounters with Ayesha. Secondly, and a rather advanced notion for the times, the women in this country are independent, neither considered chattels nor subordinate to men, and are free to choose their own lover. But it is only now that Leo meets Ustane (Rosenda Monteros) rather than in the film which brought them together almost immediately. Here, they also meet Billali (Christopher Lee) whom Holly rescues from a swamp.

With Leo still ill, it is Holly who first encounters Ayesha, who dresses as she will in the film, in a gauzy white material. In the writer’s eyes her beauty lay in her “visible majesty” as well as more obvious physical features, which could not be dwelt on at such length in a Victorian novel. Holly falls in love with her on the spot, even though he is “too ugly” to be considered a potential suitor, and learns of the fate of the earlier Killikrates and also catches a glimpse of her bemoaning her fate, imprisoned in immortality for two thousand loveless years.

“It is hard for a woman to be merciful,” proclaims Ayesha as she puts to death the villagers. Throwing them down the pit was invented by the screenwriters. By this point Leo is nearly dead and only saved by a phial administered by Ayesha. She also decrees that Ustane must die because “she stands between me and my desire.” In the film it is Leo who intervenes to attempt to save Ustane. But in the book it is Holly. He blackmails Ayesha, threatening to reveal her secret, that she had killed Killikrates in the past. Ustane claims she has taken Leo as her common-law husband. Ayesha promises to spare Ustane if she will give up her claim to Leo and go away. But Ustane refuses. In the book, there is an astonishingly visual and terrifying scene where, in revenge, Ayesha claws at Ustane’s black hair, leaving there the imprint of three white fingers.

It is the film that introduces the element of palace intrigue, with rebellious subjects and Billali believing he is entitled to immortality. That is not in the book.

When Leo finally wakes up, he is reunited with Ustane, but Ayesha catches them and kills Ustane, not by throwing her down the pit, but by her magic power. Despite being appalled, Leo cannot resist Ayesha. Even so, he is fully aware of his predicament, believing he has been “sold into bondage” and forced to love a murderess. But when she enters the sacred flame – naked, it has to be said, in the book, which was an exceptionally daring image for that era – she dies.

Holly in the book is more a narrator than a protagonist and shifting the emphasis more squarely back to Leo suits the film’s dramatic purpose. There was no real reason the film could not have followed the thrust of the book except that it would perhaps cost more costly to bring a jungle and swamps to life than a desert and arid mountains. More importantly, perhaps, was the need to introduce the physical Ayesha more quickly than in the book.

It is worth pointing out that the concept of She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed was not so alien to British readers. After all, when the book was published, the country was ruled by a woman, Queen Victoria. And although democracy had reduced elements of her absolute power, the people still had to bow down before her. In addition, the British celebrated the rule of a previous female monarch, Queen Elizabeth I, who had been an absolute ruler, in the days before there was any notion of democracy and Parliament, and in those days anyone who opposed such a figure was liable to meet as swift a death as that meted out by Ayesha.