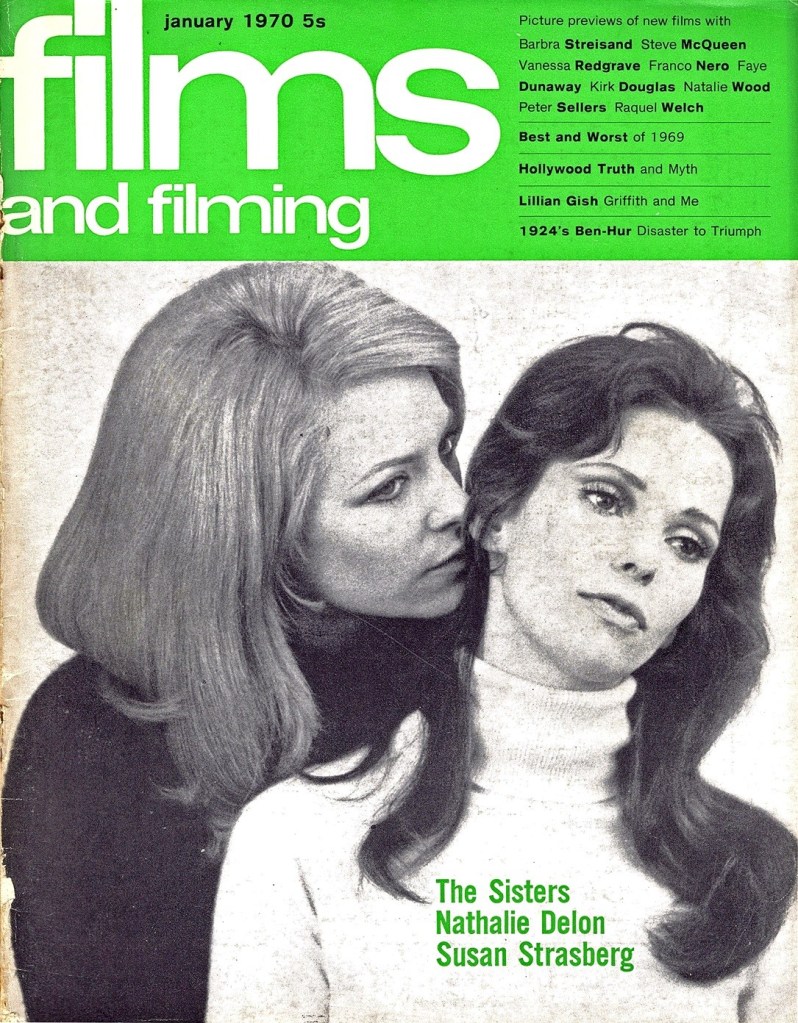

Erotically-charged, symbolically-heavy French drama of siblings trying to re-establish the intense relationship they enjoyed as teenagers. After a nervous breakdown and on the point of divorce, blonde translator Diana (Nathalie Delon) seeks respite at the home of younger sister Martha (Susan Strasberg), a brunette happily married to the wealthy and indulgent Alex (Massimo Girotti).

Initially, the more worldly Diana, the more flamboyant dresser, appears the superior but it soon transpires she is the more fragile. The apparently timid Martha allows her husband to control her life to the point of buying all her clothes and she confesses to feeling as if she is on “a perpetual cruise.” While on the surface, it seems as if she has given up too much, in reality she disapproves of disorder and seeks perfection. She comes across as needing protection, and believes the woman’s role is to sacrifice, but in fact has managed to arrange her life to her own satisfaction.

Their competitive streaks emerge in different ways, Diana in obvious fashion, seeking to beat her sister while out horse-riding, Martha in more subtle and sensual manner, flaunting her sexual relations with her husband, almost offering her sister to her husband, and having a lover (Lars Bloch) on the side. There is a sense of each attempting to impose their world view on the other. Diana gives her sister a make-over, a new look which Alex adores, Martha hates it. There’s a sense of a chess game, males the obvious pawns.

Sensuality is never far away. Diana nuzzles her sister’s neck to smell her perfume. Alex is photographed, encouraged by Martha, in almost intimate mode with Diana. Dario (Giancarlo Giannini) is brought in to tempt Diana. And a scene where the girls experiment with colorful scarves suggests libertarianism.

But it is clear that both sisters live empty lives devoid of true love and equally obvious as the picture progresses that both have arrived at the conclusion that they were at their most happiest when together. There are subtle hints of incest, comforting each other in bed, the sensuality electric and the film begins to examine whether this taboo can be crossed and, if so, will it provide the necessary escape.

Despite Martha’s apparent subjugation, there is more than an inkling of feminism, the girls involved in a complicated scenario in which males are either rejected or made to look fools. While not fulfilled, Martha has turned as much as possible to her own advantage and Diana seems perfectly capable of taking what she wants.

Alex provides the symbolism. He cultivates rare plants in a greenhouse that need to hide from the sun, lengthy exposure to whose atmosphere would be fatal to humans. He endlessly photographs them because they won’t last long. And in similar fashion provides a haven for the apparently vulnerable Martha.

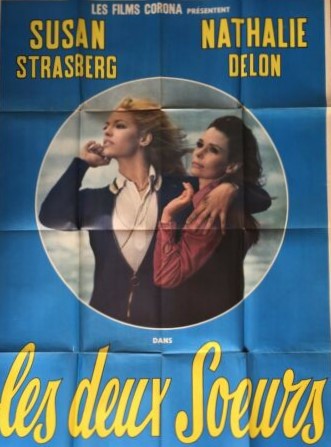

Nathalie Delon (When Eight Bells Toll, 1970), married at this point to Alain Delon, shows a subtlety of expression that is rare for someone appearing in just her third film, and effects a gradual character transition throughout. Susan Strasberg, daughter of famed acting coach, Lee Strasberg, inventor of the Method Style of Acting, was one of the boldest actors of her generation, appearing in drug pictures The Trip (1967) and Psych Out (1968). She delivers an excellent portrait of a woman who manages to keep her true personality hidden, and for whom sexuality has few barriers.

This is the puppy-fat version of Giancarlo Giannini (Swept Away, 1974), barely recognizable as the future arthouse superstar whose physical appearance relied on gaunt, angst-riddles features. Massimo Girotti (Theorem, 1968) is good as the husband who thinks he has everything, not realising how little he has.

Although this was an accomplished directorial debut from Roberto Malenotti, he only made one more movie. Perhaps he made enough from directing the famous Coke commercial I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing (1971).

Always intriguing, revelations continually undercutting what we think we know of the characters, but delivered in subtle European tones rather than employing Hollywood shock, each of the four main people involved changing considerably due to their interaction with the others. While certainly skirting close to the borders of what was permissible at the end of the 1960s, it does so without exploiting the actresses.

Not an easy one to find, your best bet is a secondhand copy on Ebay.