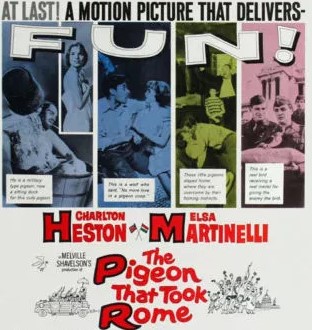

Netflix would know how to sell this. Append the “based on a true story” credit and you’ll attract a global audience. I’ve no idea how true this tale is though I assume that at certain points in war using a pigeon may have been the most efficient method of communication. If this had been under the Netflix aegis there would surely have been a scene to explain that you can’t just point the bird in any old direction but that it automatically returns to its home, that aspect being pivotal to the movie, the reason it was made in the first place.

That is, if you believe in the rather fanciful notion, as shown in what appears to be an official newsreel, of said pigeon being presented with a medal for its part in the Allied invasion of Rome in World War Two. Luckily, there’s more to this picture than the intricacies of homing pigeons.

Not much more, I hasten to add, because the other significant plot point, which I suspect has a more substantial basis in truth, is that passing American soldiers had a tendency to impregnate (and abandon) Italian women. If you were to argue that Elsa Martinelli (who had just put John Wayne in his place in Hatari!, 1962) is what saves the picture you wouldn’t be far wrong. But you can’t complain about Hollywood churning out lightweight movies in the 1960s since a chunk of the current output falls into that category.

For no apparent reason, no espionage experience for example, Yank soldiers Capt MacDougall (Charlton Heston) and Sgt Angelico (Harry Guardino) are delegated to sneak into Rome, disguised as priests, and spy on the Germans. They are put up in the household of Massimo (Salvatore Baccaloni), an underground figure, but his daughter Antonella (Elsa Martinelli) takes against the pair since they are extra mouths to feed and if only the Americans would hurry up and enter the city the populace wouldn’t be starving. However, she makes nice when her sister Rosalba (Gabriella Pallotta) reveals she is pregnant by a previous Yank (whether he was the espionage business, too, is never revealed) and is desperate need of a husband.

The sergeant is quite happy to romance the girl since a couple smooching in the park makes good cover for him transmitting messages by radio. And when that form of transmission becomes too dangerous, the Americans rely on pigeons. Soon Angelico realises his feelings for Rosalba are real and proposes to her, even after she reveals her condition. But that means celebration to announce their forthcoming nuptials.

Short of any food, Antonella slaughters the pigeons, convincing MacDougall that the meal consists of squab. To cover up, the Italians steal a bunch of pigeons from the Germans. Of course, as you’ll have guessed, that means the pigeons will return to the enemy. But once MacDougall works this out, he starts sending the Germans false messages that prove (apparently) pivotal to the Germans hightailing it out of the city (hence the medal awarding).

Pretty daft and inconsequential sauce to be sure, but Antonella keeps matters lively, knocking back MacDougall at every turn, taking every opportunity to condemn men for starting wars, and presenting herself as something of a conniver, possibly willing to lead on the Germans in return for food (MacDougall when burglarizing a German villa comes across her naked in the shower). Her occasional swipes give the picture a harder edge than you’d expect, but, her fiance killed in the war, she leads MacDougall a merry dance in the manner of the romantic comedies of the day. Otherwise, the comedy is for the most part lame, the old hitting your thumb with a hammer one such moment.

Despite co-starring with Wayne and here Heston and later Robert Mitchum (Rampage, 1963), Martinelli didn’t fit into the Hollywood pattern of taking European stars and slotting them into the female lead opposite a succession of top male stars. Think Sophia Loren with Heston in El Cid (1961), with Gregory Peck in Arabesque (1966) and with Marlon Brando in The Countess from Hong Kong (1967) and headlining a few pictures on her own. Gina Lollobrigida led Rock Hudson by the nose in Come September (1961) and Strange Bedfellows (1965) and Sean Connery a merry dance in Woman of Straw (1964).

Martinelli seemed to fade too quickly from the Hollywood mainstream which was a pity because she’s the glue here. Charlton Heston (Number One, 1969) spends most of the time looking as if he wondered how he managed to allow himself to be talked into this. You want to point the finger, then Melville Shavelson’s (Cast a Giant Shadow, 1966) your man – he wrote, produced and directed it.

Worth it for Martinelli.