I should mention the George Lucas connection right away because, for some, that is the movie’s main contemporary connection.

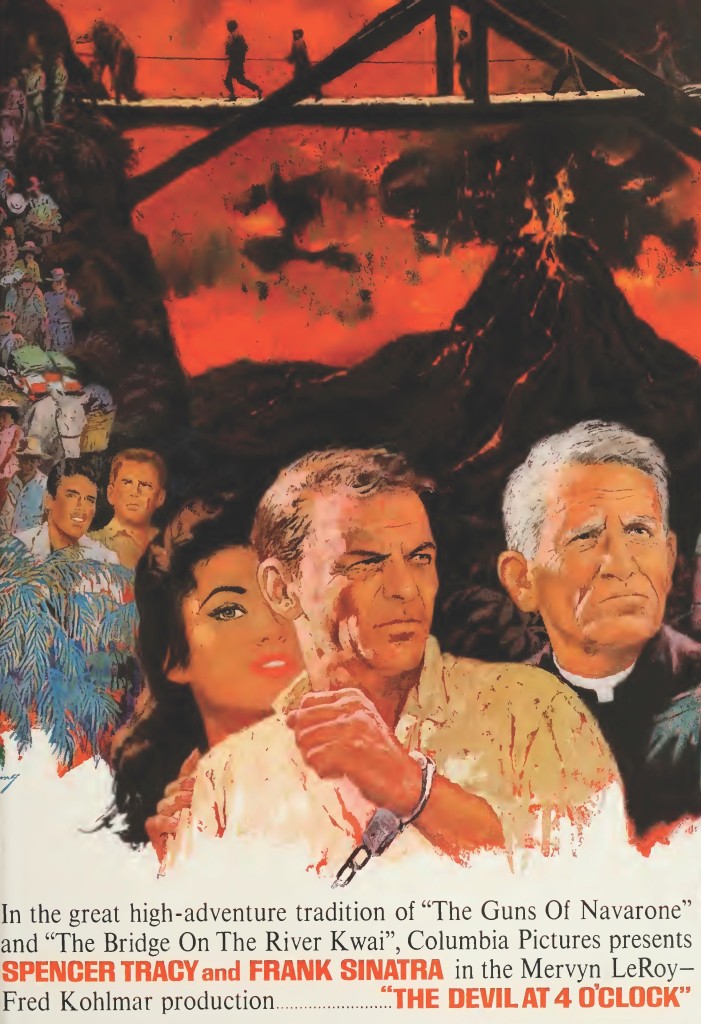

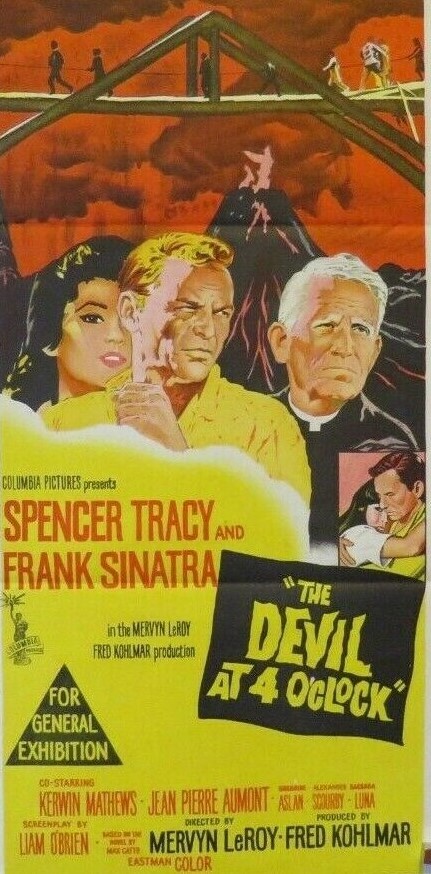

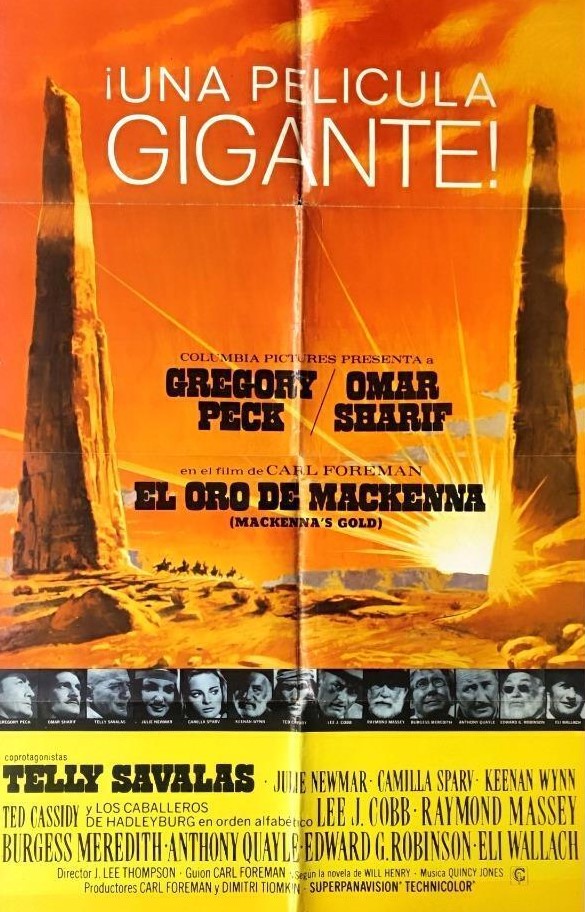

Mackenna’s Gold was originally intended as a three-hour movie[i] for roadshow release to be shot in early 1966 for Columbia Pictures by writer-producer Carl Foreman (Guns of Navarone, 1961) who would also be in the director’s chair.[ii] But outside of How the West Was Won (1962) westerns had foundered in roadshow. The Alamo (1960), John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn (1964) and John Sturges The Hallelujah Trail (1965) were surprising roadshow flops. Foreman persuaded Columbia to increase the budget to $5 million – and then beyond – and film the movie in Cinerama, (over 25 percent of the budget was allocated to Cinerama to license the name and use the equipment – $1.35 million in total of initial negative costs[iii]).

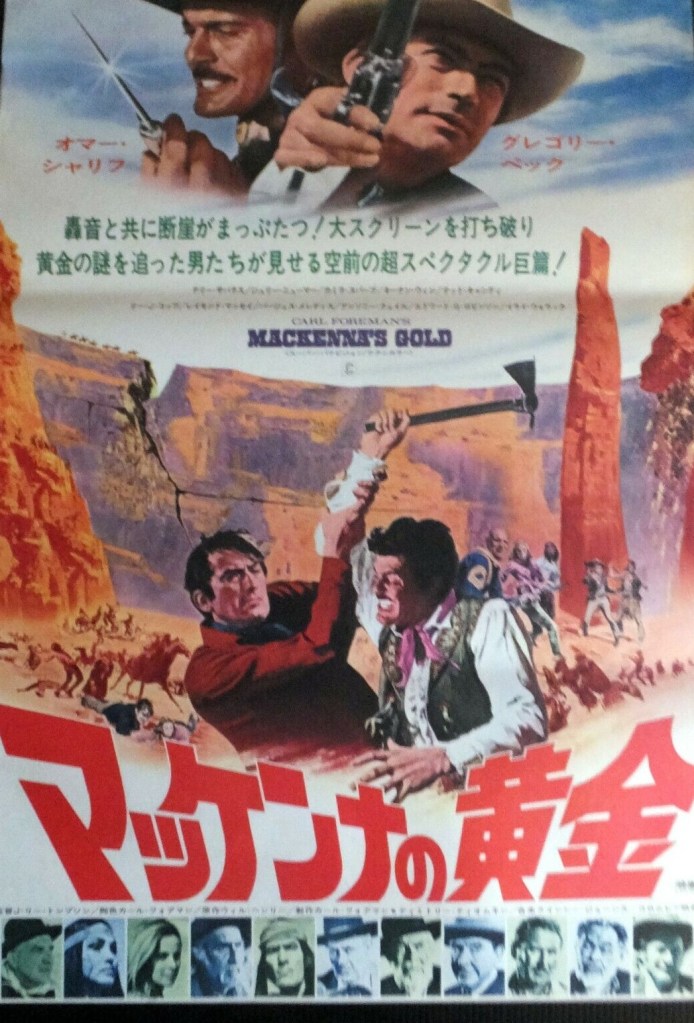

In January 1967 Columbia launched the marketing campaign with full page advertisements in the trade papers promoting the fact that the movie would be filmed on location in the USA in Cinerama and that it would bring together the “creators of The Guns of Navarone,” meaning, at this point, Foreman and director J. Lee Thompson. The advertisement also highlighted author Will Henry, on whose novel the film was based (as the “author of San Juan Hill and From Where the Sun Now Stands”) and plugged the book as “a novel of Apache gold and Apache revenge based on the search for the fabulous Lost Adams Diggings.” By the following year, Foreman’s star was in the ascendant after the Parisian revival of High Noon[iv] and Columbia had another two major roadshows planned for the 1968-1969 season: Barbra Streisand’s movie debut in William Wyler’s Funny Girl also starring Omar Sharif and Carol Reed’s Oliver! [v]

By this time, Columbia had reshaped its marketing effort to provide the specialist support required for promoting roadshows. In early 1967, it had poached sales guru Leo Greenfield from Buena Vista with the express aim of setting up an effective unit to market hard-ticket product – “first assignment Mackenna’s Gold, Oliver! and Funny Girl”[vi] – to the record number of Cinerama theaters[vii] and those desperate to accommodate roadshow. By the end of 1968, both Cinerama and Columbia had reported record revenues and profits, the former turning a $290,000 loss into a $679,000 profit,[viii] the latter on an unprecedented streak of success with a gross profit of $9.3 million profit on a gross income of $239 million.[ix] Columbia soon added another roadshow prospect to its slate, Sydney Pollack’s World War Two drama Castle Keep starring Burt Lancaster, and was so confident about the two non-musicals, for example, that it expected the western and the war picture to run consecutively from late spring 1969 well into the following year at Loews Hollywood in Los Angeles.[x] Funny Girl hit $550,000 in advance sales – $80,000 was the usual figure.[xi] Mackennas’s Gold’s was scheduled to premiere in Phoenix, Arizona, on February 15, 1969, with the roadshow launch set for the DeMille theater in New York five days later.

Within the next month, however, the world premiere was called off, work began on editing down the near-three-hour running time, and plans, two years in the making, for an ambitious roadshow release were quietly dropped. Public reaction to The Stalking Moon – also starring Gregory Peck – was one reason. Two other Cinerama movies, Custer of the West (1967) and Krakatoa – East of Java (1968) had also flopped. If Mackenna’s Gold was to be marketed as a drama in a western setting rather than a shoot-out in the tradition of 100 Rifles, then Columbia looked worryingly at Isadora, boasting a 177-minutes running time, whose roadshow run in Los Angeles was swiftly truncated, and the movie butchered in a bid to find an audience.[xii]

The studio took a different tack. The world premiere shifted to Munich, West Germany, in March[xiii] with most of the rest of the European capitals holding gala premieres (and running it as roadshow or at least 70mm) before the picture made its U.S. debut in Phoenix on May 10. But the picture unveiled in Phoenix was a ghost of the original. The running time technically came in at 128 minutes, but, in effect, was under two hours long, the introductory narration lasting eight minutes and the end credits accounting for further time. However, what was oddest of all was the 18-month gap between completion and world premiere. Filming had begun on May 16, 1967 and wrapped on September 29. Columbia had shelved one of its biggest budgeted movies for nearly 15 months.

The movie had a troubled history. For a start, Foreman didn’t own the rights to the Will Henry source novel. Dmitri Tiomkin, after a debilitating eye condition restricting his composing career, had in 1964 purchased the rights. Tiomkin agreed to sell the rights to Foreman in April 1965 in return not just for a fee and an agreement to compose the music[xiv] but also the vital producer’s credit necessary to launch him on a new career.[xv] Foreman was initially keen on filming the movie in Spain to take advantage of generous government subsidies.[xvi] But Foreman was demoted from director. His last picture as writer-producer-director The Victors (1964) had flopped. The studio did not want to offer the producer any distraction from the complex logistics of a location shoot where much of the time the crew would be 50 miles from the nearest town and where, despite the desert environment, could be subject to storms and flash floods. Instead, J. Lee Thompson (The Guns of Navarone) came on board as director. (Thompson was also at this point lined up to direct Charlton Heston in Planet of the Apes, whose rights he co-owned.)

However, the Thompson-Foreman relationship did not run smoothly. Foreman recalled: ‘I was not very happy with the work of J. Lee Thompson on that film and entirely apart from that we still got into trouble in terms of scheduling and so forth and our relationship was always a problem.’[xvii] Logistics were always going to be an issue on a picture of this scale, shot almost exclusively on some of the most inhospitable places on Earth. The buzzard section was filmed in Monument Valley on the Arizona/Utah border, and other scenic wildernesses included the Glen Canyon of Utah, Spider Rock in Canon de Schelly in Arizona, Kanab Valley, Sink Valley, the Panguitch Fish Hatchery in Utah, and Medford in Oregon.

Gregory Peck was not first choice for the titular role in Mackenna’s Gold. He only got the part after Steve McQueen and then Clint Eastwood had turned it down[xviii] and even then Peck wavered, only agreeing after pressure from Foreman, and in recognition of their work together on The Guns of Navarone.[xix] Depending on your point of view, Omar Sharif was miscast or cast against type, a matinee idol whose character, in ruthless pursuit of gold, eschewed any element of romance. By the time the movie appeared, Sharif’s marquee appeal had taken a tumble. MGM’s Mayerling and Twentieth Century Fox’s Che had flopped, The Appointment (1969) shelved and Funny Girl’s success rightly attributed to Streisand.

Over the past few years, Telly Savalas had discovered the harsh reality of Hollywood. An Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor in The Birdman of Alcatraz (1962) had done less for his career than the odious Maggott in The Dirty Dozen (1967) after which he was promptly promoted to third billing on Sol Madrid (1968), western The Scalphunters (1968) and The Assassination Bureau (1968). Although he retained that billing on Mackenna’s Gold, he did not appear until halfway through, suggesting that his role as Sgt Tibbs had been a casualty of the editing needed to reduce the running length. Camilla Sparv had been leading lady in Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round (1966), Assignment K (1968), and Nobody Runs Forever (1968). Newmar, a decade older, was best known for playing “Catwoman” in the television series Batman (1966-1967). Foreman had given her the leading female role opposite Zero Mostel in Monsieur Lecoq (1967) but the movie was unfinished, although Newmar still attracted attention after stills from the picture appeared in Playboy magazine. Mackenna’s Gold aimed to set a new standard in the quality of actors in supporting roles – the by now requisite roadshow all-star cast including Edward G. Robinson (The Biggest Bundle of Them All, 1968), twice-Oscar-nominated Lee J. Cobb (Coogan’s Bluff, 1968), Burgess Meredith (Skidoo, 1968), Anthony Quayle (The Guns of Navarone), Oscar nominee Raymond Massey (Abe Lincoln in Illinois, 1941), Keenan Wynn (How the West Was Won) and Ted Cassidy (“Lurch” in The Addams Family television series, 1964-1966).

The George Lucas Connection

In some respects, the involvement of George Lucas (Star Wars) in Mackenna’s Gold has overshadowed that of director J. Lee Thompson. Committed to bringing through a new generation of talent, Foreman had established an internship for the picture. Lucas was one of four winners and his entry was the first version of THX 1138 (1971). The internship funded the winners to shoot a short film on the location. Foreman became immediately a fan because of the quality of Lucas’s effort. Foreman explained: “He did the shortest one of the lot and the most technically accomplished. It ran only one minute and 47 seconds and it had no title – he gave it a date – and then we agreed we’d call it A Desert Poem because he went out on the desert and did a lot of stop-action photography. George really knew his camera and he played with his camera and it was around and about the film – he was doing the desert more than anything else but in the desert was the film company with its parasols and all that shimmering in the distance and he played around with little things where the sun was shining and the film company was working. And then it began to rain, and it rained like hell, and then the sun came out again. It was awfully good. He did a lot of trick stuff with his camera and that’s what the boys resented, that he could just go out by himself and do that.”[xx]

The “boys” resented Lucas for more than his technical accomplishment but Foreman’s admiration for the neophyte director increased after seeing a display of professionalism that put the other professionals to shame. “We were…in a very difficult location…near the place where we had painted in this great seam of gold…We got to the big scene, the scene where they (the actors) all discovered it (the gold), and they all started running towards it…But it (the location) was in a kind of ravine and there was a problem about the light – you could only shoot it…at that time of year when the sun was more or less directly overhead or had just begun to go down or had just passed the meridian…(but when Foreman arrived on location) the entire company was just sitting there. Lucas therefore pointed out in an indirect manner that the scene had not been rehearsed because J. Lee Thompson was waiting for the sun to rehearse it during the precious moments when the sun was there instead of being ready for when the sun was there.”[xxi]

Reception

Trade magazine Variety came out in overall favor of Mackenna’s Gold: “splendid western, stars plus special effects and grandeur should insure box office success.”[xxii] Hollywood Reporter predicted, “Audiences should queue up,” and Film Daily proclaimed “a fine, exciting western adventure.”[xxiii] However, Vincent Canby in the New York Times called it a “truly stunning absurdity,” The New York News, while generally positive, nonetheless complained it was “sprawling” and “pretentious.” New York magazine and the Washington Post were among the nay-sayers.[xxiv] Perhaps, Peck’s own opinion was the most damning: “Mackenna’s Gold was a terrible western, just wretched.”[xxv]

Star fatigue did not occur in the days of the studio system, when releases were carefully spaced out to give the public a breathing space between each release. Actor independence meant timing of releases was removed from studio control – Gregory Peck’s movies in 1969 came from three different studios, Universal (The Stalking Moon), Twentieth Century Fox (The Chairman) and Columbia (Mackenna’s Gold), and Omar Sharif was in the same position with MGM for Mayerling, Twentieth Century Fox for Che and the western from Columbia. As you might expect, releases were not coordinated, studios did not sit down around a table and discuss how to avoid each other’s movies clashing. So in the first six months of 1969 audiences were treated to three pictures apiece from the stars, the earlier ones flops though Mayerlingr was a big hit overseas.[xxvi] Whatever the reason, Mackenna’s Gold did not race out of the gate. Its final rentals tally of $3.1 million – 42nd spot in the annual chart,[xxvii] ahead of The Stalking Moon and Once Upon a Time in the West, but well below the much less expensive Support Your Local Sheriff and 100 Rifles. In budget terms it was close to a disaster. However, it was a huge hit in India, setting a record in Madras for the best showing for a foreign picture.[xxviii]

SOURCES:

This is an edited version of a much longer chapter from my book, The Gunslingers of ’69: Western Movies’ Greatest Year.

[i] Sheldon Hall has argued that the movie was never intended to be three hours long and that judging from a screenplay of 145 pages the film would have been roughly two-and-half-hours long. He identified a major sequence that was filmed but edited out – of another battle between the Apaches and the gold-seekers (“Film in Focus, Mackenna’s Gold,” Cinema Retro, Issue 43, 40.)

[ii] “Foreman to Start Gold, Delays Churchill Pic,” Variety, September 8, 1965, 4. The Churchill project would eventually become Young Winston made in 1972 for Columbia. The movie was originally postponed due to political unrest in the chosen movie locations.

[iii] Filmmakers licensing the Cinerama name had to pay $500,000 upfront and Foreman was committed to spend $875,000 for Cinerama camera equipment. The cost might escalate because Columbia also had to agree to pay Cinerama 10 percent of the gross (“C’rama Sets Major Int’l Expansion As More Pix, More Theaters Use Process,” Variety, November 15, 1967, 25).

[iv] “Junket for Noon Sparks Nostalgia,” Variety, April 24, 1968, 31. Not only was the revival a critical success but it was a box office hit all over again in Paris.

[v] “Leo Greenfield’s Chore,” Variety, May 31, 1967, 8. Wyler, of course, was the king of the roadshow, having directed Ben Hur. Reed had directed The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965) after an initial chastening experience with roadshow having pulled out of MGM’s Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) after clashing with star Marlon Brando.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] “C’Rama Sets,” Variety. There were 250 theaters in the U.S. and 2100 worldwide equipped to show Cinerama.

[viii] “13-Week $679,000 Contrast Year Ago,” Variety, November 20, 1968, 14. The figures compared September 1967 to September 1968.

[ix] “News in Col Annual Report Is ‘Solid Solvency,’” Variety, November 4, 1968, 3.

[x] Switching of Isadora from Hard Ducat,” Variety, January 15, 1969, 7

[xi] “Third Road Show Study,” Variety.

[xii] “Switching of Isadora,,” Variety. The film, which had opened on December 18, was set to close on February 8 and go straight into continuous performance.

[xiii] “Col Bows Gold in Munich to Spark Lagging Box Office,” Variety, March 26, 1969, 41; “Mackenna’s Gold Launching Pattern,” Variety, March 5, 1969, 28. While it was true the studios were concerned about falling box office in Europe, the true reason for launching the picture in Europe ahead of America was because Foreman was so much better known there courtesy of his major marketing blitz for The Guns of Navarone and The Victors. It opened in Paris and Rome in March and in April in London.

[xiv] By the time the movie came out, Tiomkin had given up composing and the score was done by Quincy Jones.

[xv] “Tiomkin-Foreman Partners for Col,” Variety, April 21, 1965, 19.

[xvi] “Cash Advantages,” Variety.

[xvii] The Carl Foreman Tapes, Transcripts of Tapes between Sidney Cohn and Carl Foreman, Carl Foreman Collection, ITM – 4408, (Tape V – A, December 20, 1977, British Film Institute, Reubens Library, London).

[xviii] Avery, Kevin ed, Conversations with Clint, Paul Nelson’s Lost Interviews with Clint Eastwood, 35 ; Neibaur, James L, The Clint Eastwood Westerns, 44.

[xix] Fishgall, Gary, Gregory Peck, A Biography (Scribner, New York, 2002), 264.

[xx] The Carl Foreman Tapes

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Review, Variety, March 26, 1969, 6.

[xxiii] Advertisement, International Motion Picture Exhibitor, May 7, 1969, 12.

[xxiv] “Crix Boxscore on New Pix,” Variety, June 25, 1969, 28.

[xxv] Fishgall, Gregory Peck, 265.

[xxvi] Sick Tops Italo ‘68-’69 Box Office,” Variety, July 23, 1969, 31. Mayerling ranked ninth at the box office for this period. .

[xxvii] “Big Rentals of 1969,” Variety.

[xxviii] “Gold Sets Madras Record,” Variety, December 2, 1970, 26.