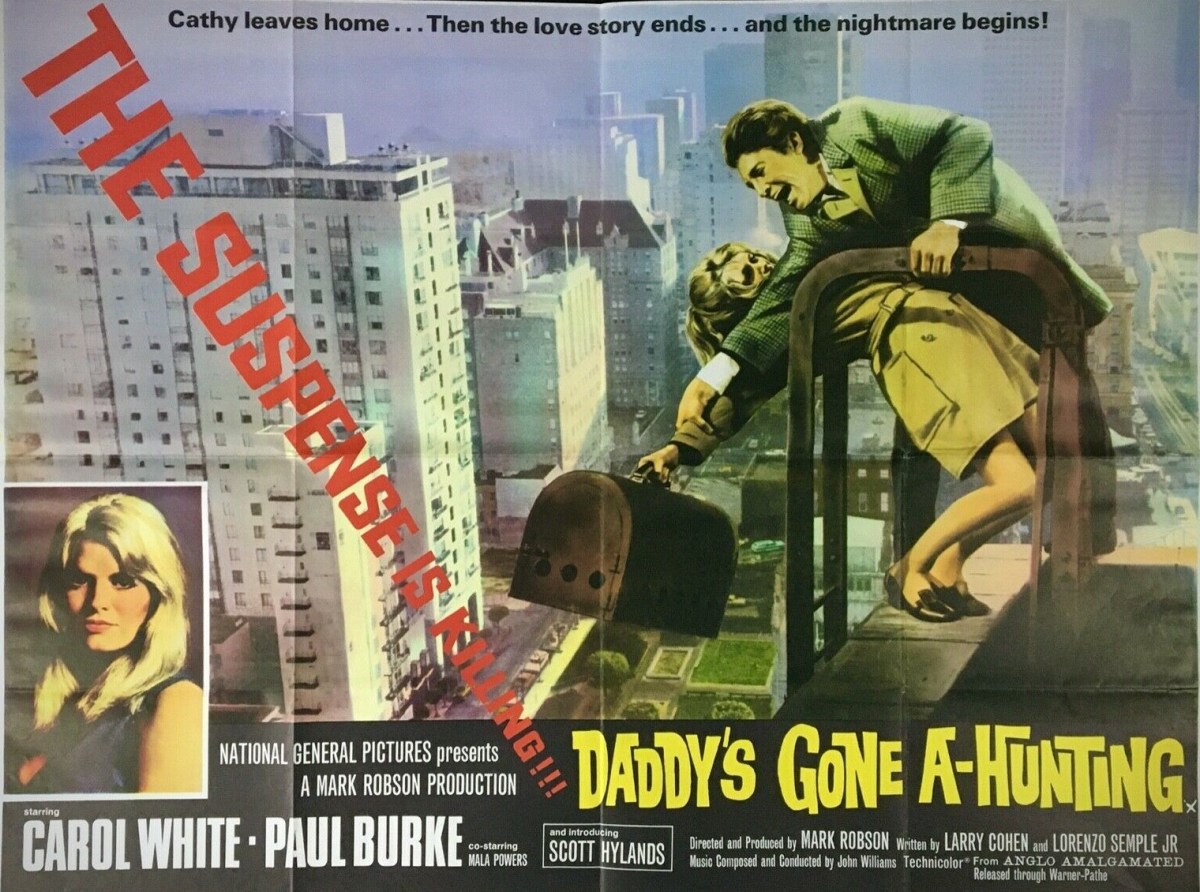

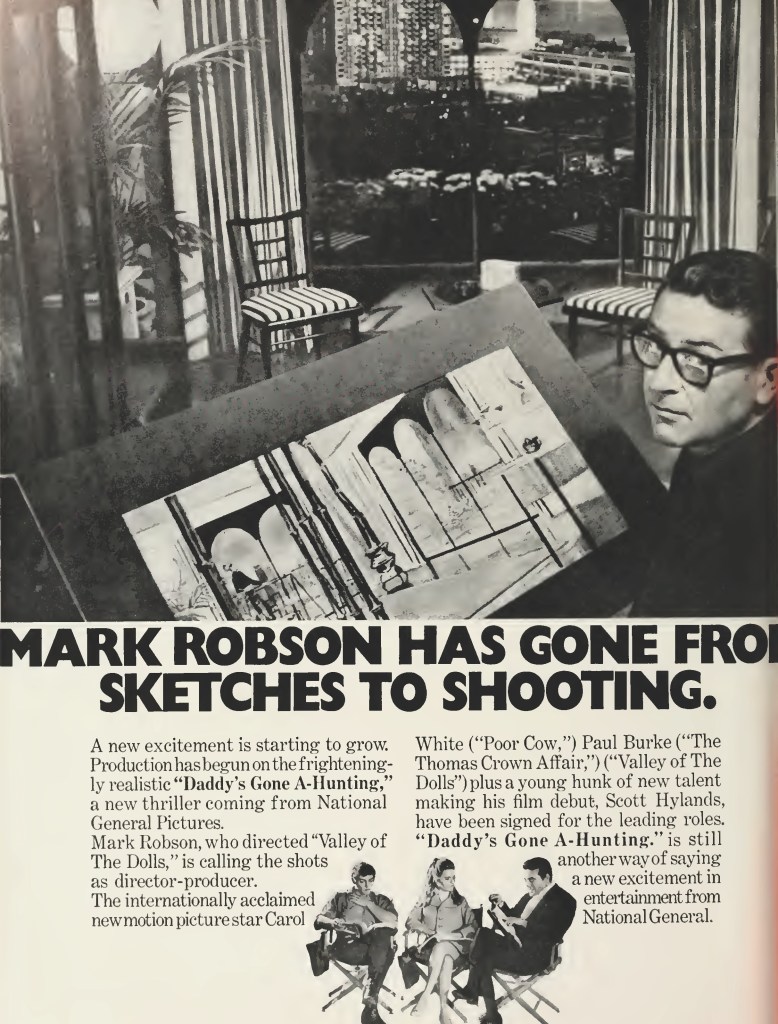

Everyone wants to be a star-maker. Director Mark Robson thought he had some form in this area after Valley of the Dolls (1968) showcased Barbara Parkins and Sharon Tate. There’s no doubt British actress Carol White reveling in critical kudos for Poor Cow (1967) had promise. But not necessarily good professional advice otherwise how to account for a supporting role in Prehistoric Women/Slave Girls (1967) her first picture after success in three BBC television productions. The female lead in Michael Winner’s I’ll Never Forget Whatisname (1967) was followed by a small role in the more prestigious John Frankenheimer drama The Fixer (1968). But none of these films did anything at the box office. Enter Mark Robson.

This thriller might have made her a star had it not been so darned complicated. It veers from paranoia to stalkersville to Vertigo via Gaslight without stopping for breath and some elements are so obviously signposted at the start you are just waiting for them to turn up. Plus, if ever a film has dated, it’s this one, going back to the days when abortion carried automatic stigma and fathers could get away with lines like “you murdered my baby.”

So, one of the few times in history San Francisco got snow (it averages zero inches annually according to Google) the meet-cute is sketch artist Cathy (Carol White) being hit by a snowball thrown by wannabe Kenneth (Scott Hylands, making his debut). But when she realizes how much he enjoys watching cats stalking canaries decides she doesn’t want his baby and aborts it.

A few years later she marries congressional candidate Jack (Paul Burke from Valley of the Dolls) and when pregnant crosses paths with Kenneth who manages to insinuate himself into her family via her husband. Twist follows twist until we are on the Top of the Mark (a famous city landmark) for a gripping climax.

White does well as she shifts through the emotional gears but she is barely given respite from being overwrought so at times her acting appears one-dimensional rather than varied. In fairness to her, the movie’s plot gives her no chance to deliver a settled performance. Hyland looks as if he’s auditioning for a role as a serial killer, but the depth of his cunning and his twisted perceptions kept this viewer on edge – what it would take for Cathy to make amends will chill you to the bone.

Robson has some nice directorial touches, a scene reflected in the eye of a cat, a clever jump-cut from marriage proposal to marriage ceremony and some flies in milk. Mala Powers makes a welcome big screen appearance after nearly a decade in television. That this whole concoction emanated from the fertile imaginations of screenwriters Larry Cohen (It’s Alive, 1974) and Lorenzo Semple Jr. (Fathom, 1967) might give you an idea of what to expect.