Given the severity of the crime involved, you leave Frank Perry’s coming-of-age-drama wondering what happened to the four principals. Did the aggressive three young demi-gods of a golden age go on to pursue similar acts of cruelty? While one of them might show remorse, or at least suffer from guilt, of the other two I have my doubts. They would find ways to blame the injured party. And what about the victim? Would she have the courage to report the crime, or suffer in shame for decades.

It’s odd how time changes entirely the shape of a movie. In its day this was seen as a bold exposition of frank adventure by teenagers seeking their first experiences of growing up and experimenting with sex and drugs (pilfered from a parental stash). Although there is little focus on dysfunctionality, both Sandy (Barbara Hershey) and Rhoda (Cathy Burns) are missing a parent, the former’s father running off with another woman, the latter’s mother drowned by stupid misadventure. Both have been abused, unable to prevent the wandering hands of males. All are vulnerable, if only by youth.

Of the boys, Dan (Bruce Davison) is the more confident, Peter (Richard Thomas), while easily swayed, the gentler of the two. Dan merely seeks his first taste of sex, Peter the more likely to need love as well. Sandy is sexually precocious, somewhat on the exhibitionist side, peeling off her bikini top with apparently at times no idea of the effect it will have on the boys, at other times clearly uncomfortable with the notion that the guys might have nothing else on their minds but staring at her breasts. But she is the one who wants to continue watching a gay couple cavorting on the beach while Dan is embarrassed. Sometimes the frank sexuality is rite-of-passage stuff, other times it is distinctly creepy. In the cinema both men grope her breasts. She claims to have been excited by the experience, but you can’t help thinking at least one of the men should have shown restraint, not treating her as if she was some kind of sex toy.

The movie begins on a clearer note. The guys come across Sandy nursing a wounded gull and perhaps entranced by her good looks help her remove a hook from the bird’s throat, provide convalescence and eventually help the bird recover the confidence to fly again. It’s a cosy trio, but edgy, too, Sandy allowing them considerable latitude. But, of course, the guys do the same to her. When she bludgeons the bird to death because it bit her (“the ungrateful bastard”), the pair, initially shocked, are not shocked enough to reject her, afflicted by unassailable male logic, the kind that drove film noir, that maintained a beautiful woman could not have a black heart.

Separated from the other two, Peter displays a gentler side, teaching the shy Rhoda to swim, kissing her in far more considerate fashion than the boys treat Sandy. But, effectively, she is a pet, and it’s only a matter of time before the unsavory aspect of Sandy’s character breaks out. After setting Rhoda up on a date, the trio do everything they can to spoil it, angry at the poor girl for not getting the “joke.”

Worse is to follow. Date-rape we’d call it today. Retreating to the cool forest, Sandy taunts Rhoda by removing her bikini top. When the horrified Rhoda refuses to do the same, Sandy attacks her, holding her down along with Peter while Dan rapes her. That’s where the film ends, no consequences, no repercussion. Back in the day it was a shock ending, an act of violence to mar an otherwise relatively innocent summer. After the deed is done, the camera pulls back into an aerial shot to observe the guilty trio walking back to the beach, but without drawing conclusion or offering moral judgement. It’s hard to know what to make of the ending. These days, of course, we’d be appalled. But back then it didn’t appear to appall, certainly not drawing the outrage that accompanied similar scenes in The Straw Dogs (1971) or A Clockwork Orange (1971) perhaps because the perpetrators were so attractive and it was, after all, a coming-of-age picture, as if such things could be expected.

Roger Ebert, writing in the Chicago Sun-Times, for example, judged that the conclusion “is not really important to the greatness of the movie.” Andrew Sarris of Village Voice noted that “Perry retreats from the carnal carnage” to end with a shot that “prefers symbolic evocation to psychological exploration.” In other words adolescence is fraught with risk and Rhoda is just collateral damage.

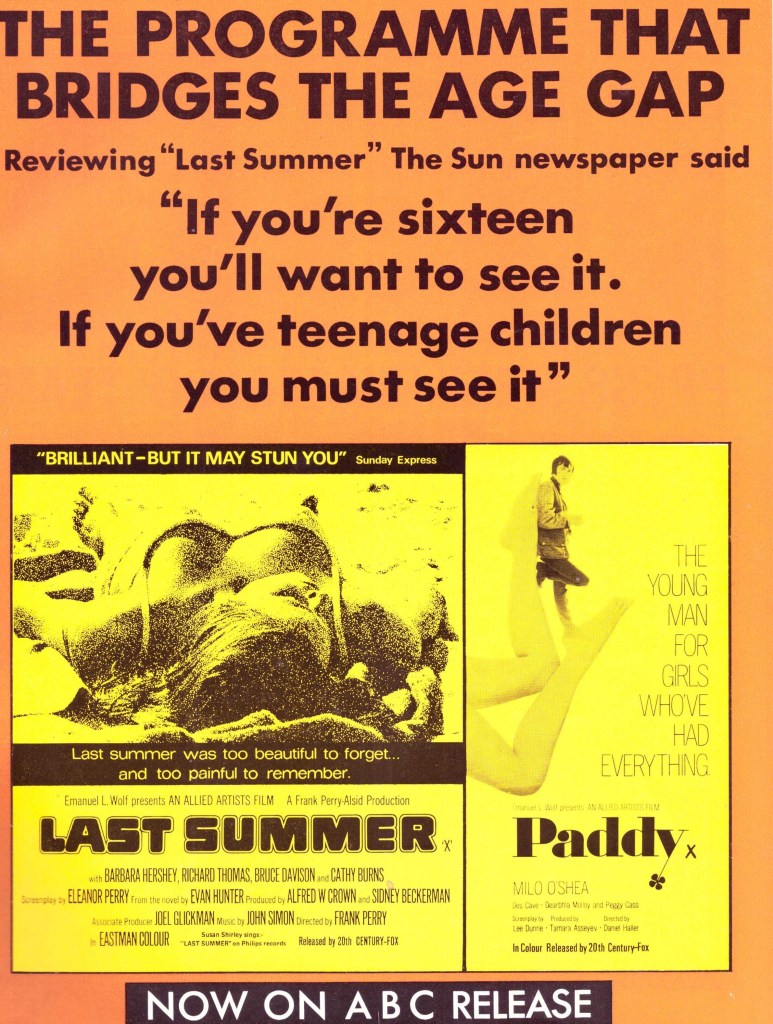

Certainly the acting is uniformly excellent for such inexperienced actors, coping with many changes in dramatic focus, from early exhilaration through growing pains to violence. Barbara Hershey (Heaven with a Gun, 1969) would go on to become a major star. Amazing to realise that Bruce Davison (Willard, 1971) and Cathy Burns, Oscar-nominated for her role, were making their movie debuts and for Hershey and Richard Thomas (Winning, 1969) their sophomore outings.

Director Frank Perry (The Swimmer, 1968) had a special affinity with the young as he had proved with David and Lisa (1962) and at times the whole affair had an improvised free-wheeling style. Eleanor Perry (David and Lisa) wrote the screenplay based on the novel by Evan Hunter (The Birds, 1963).

This is very hard to find, it turns out, so Ebay might be your best bet.

My thanks to one of my readers, Mike, for digging up this story of the disappearance of Catherine Burns from the movie business.