Early entry to the hijack subgenre – this one pivoting on the bomb-on-a-plane. Could almost deem it a template for what to do and not do in this particular field. Airport (1970) was the most obvious beneficiary although Speed (1994) could be reckoned to be something of a homage. And though “what if” was largely the preserve of sci fi, this posed very scary questions for audiences only beginning to enjoy the benefits of cheaper international travel. A quartet of excellent twists and three examples of men under pressure heat up the concept.

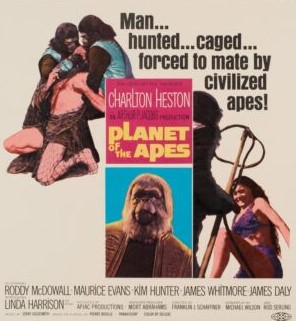

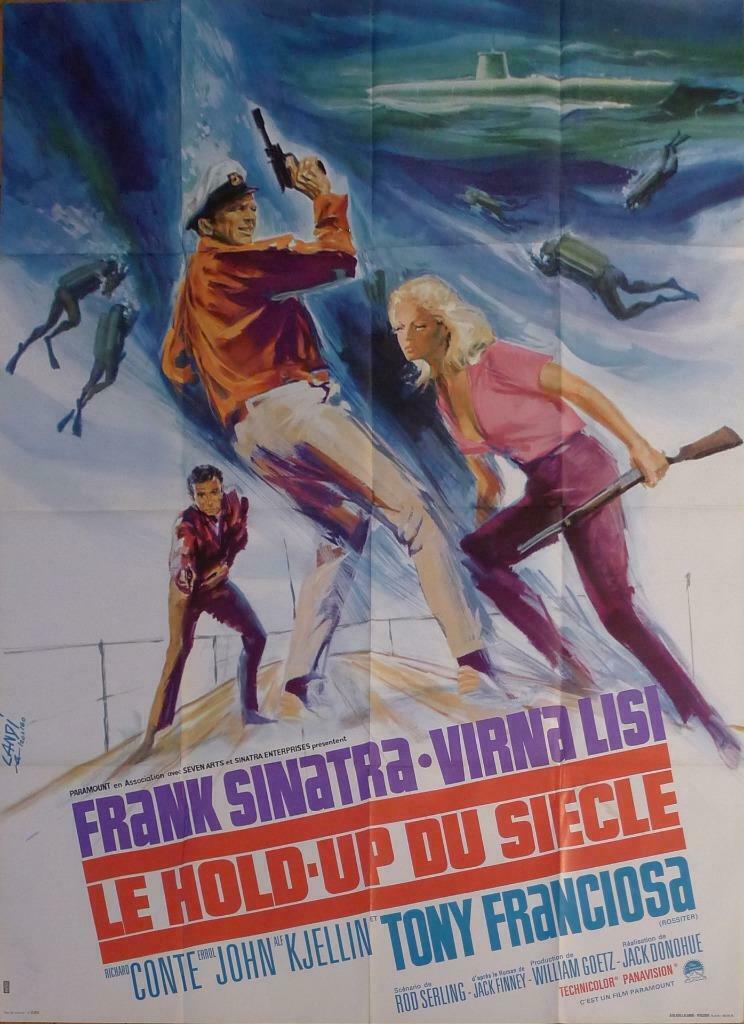

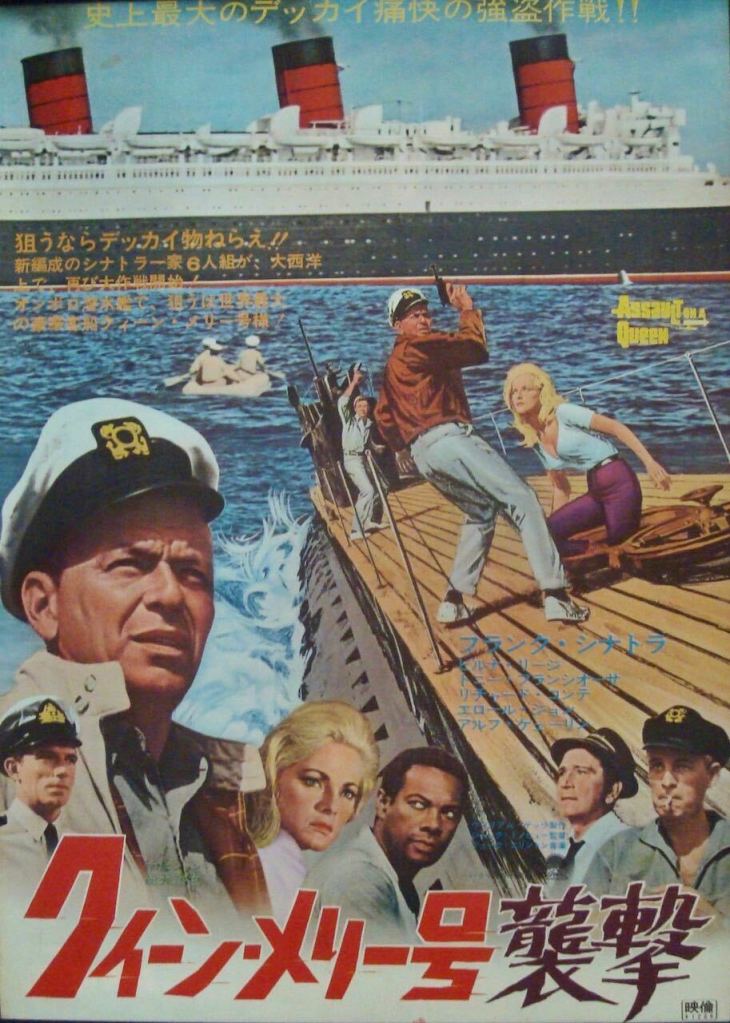

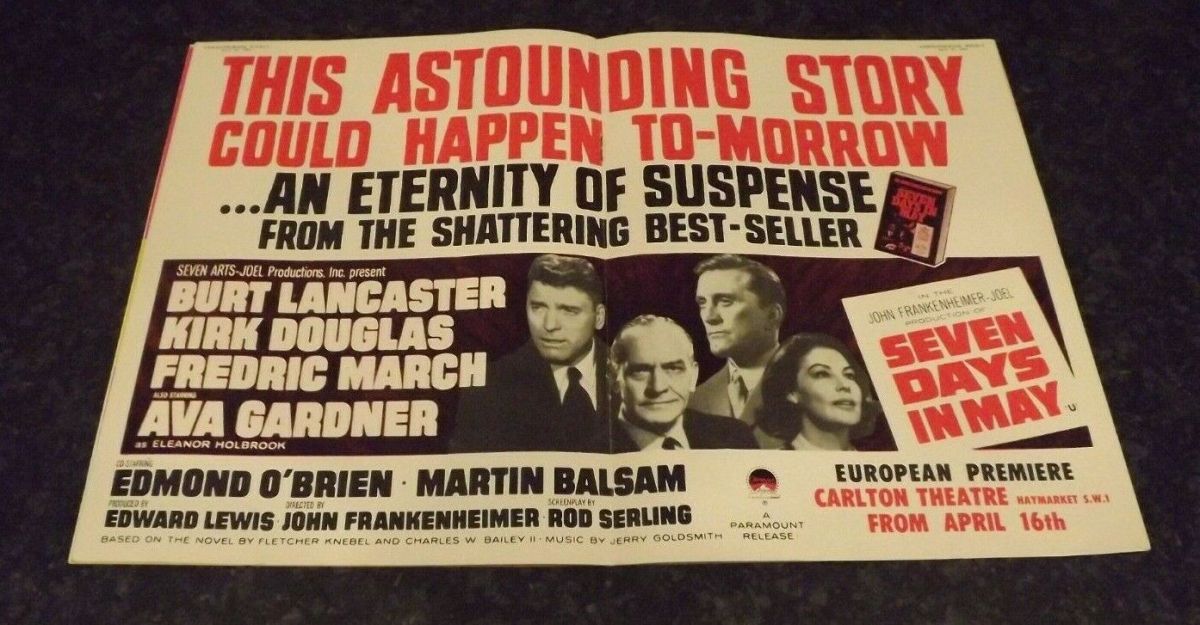

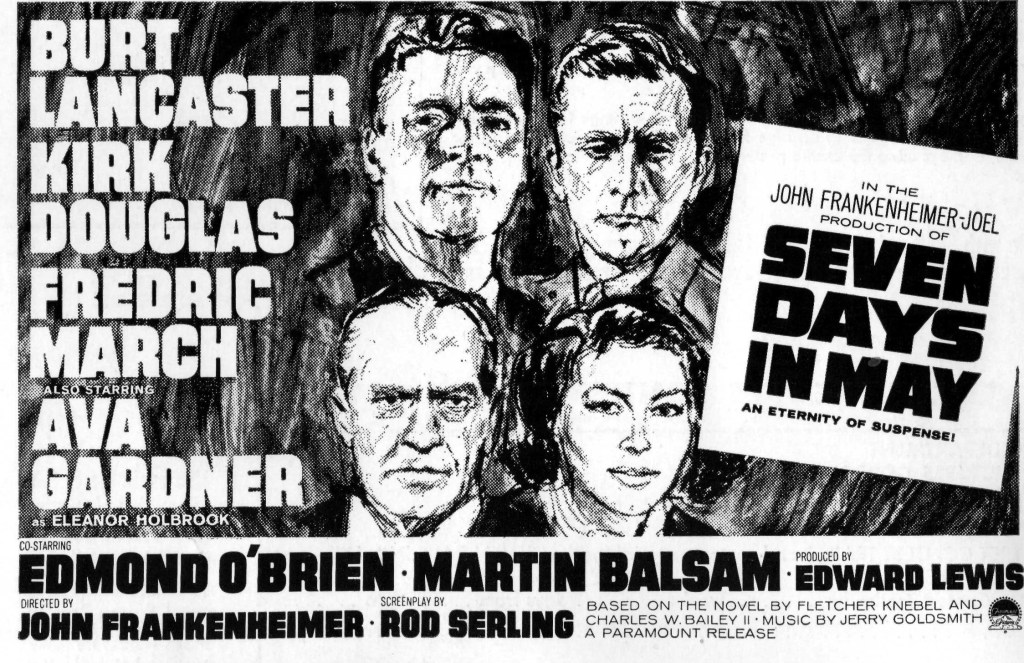

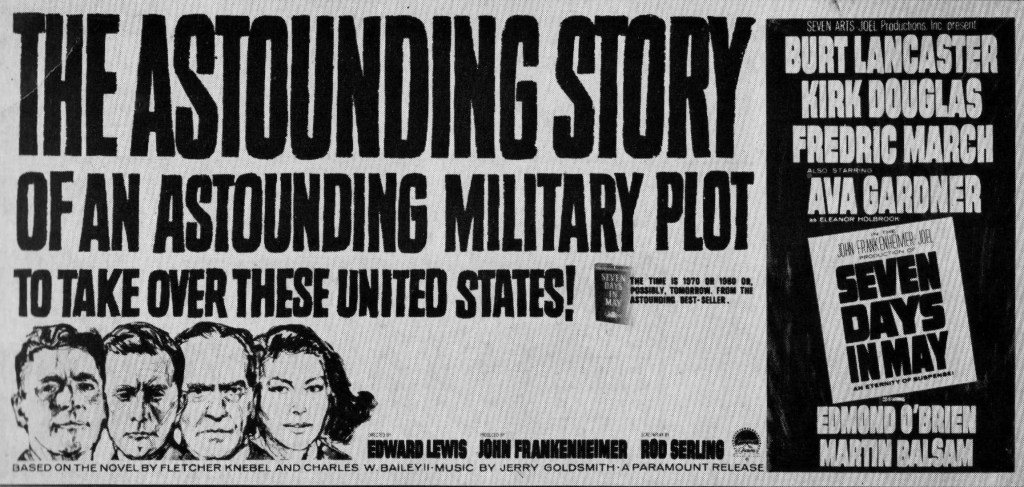

Unusually, the writer was the main selling point, Rod Serling (Seven Days in May, 1964) being more famous than most screenwriters thanks to The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) scaring the pants off viewers in ways that nobody thought television would dare to do.

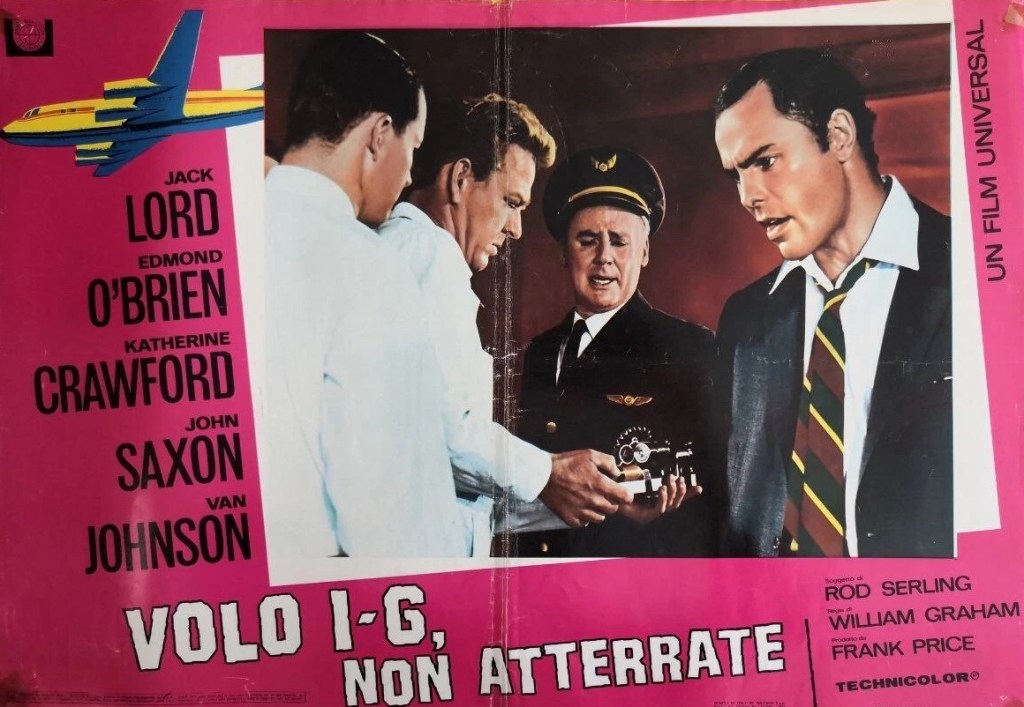

Propped up by an interesting cast – Jack Lord (The Name of the Game Is Kill!, 1968), former major league movie star Van Johnson (Wives and Lovers, 1963), Edmond O’Brien (Rio Conchos, 1964), John Saxon (The Appaloosa, 1966), Ed Asner (The Satan Bug, 1965) and Michael Sarrazin (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, 1969).

Unusual in that the two main characters lose it and the movie is probably the first to touch upon PTSD in Vietnam. While Special Agent Frank Thompson (Jack Lord), leading the task force on the ground, appears to be in complete control, in fact he’s hidden the fact that his wife is on the hijacked plane. That’s only revealed in the final climactic twist, so you have to cast your mind back over the movie and reassess Jack Lord’s apparently unflappable performance.

The anonymous hijacker (Edmond O’Brien) is a pretty cunning individual. He’s set a bomb to explode on the plane’s descent and removed the easy option of making a speedy landing by forcing the jet to remain above a certain height otherwise an altitude-sensitive trigger will blow the passengers to kingdom come. He demands a $100,000 ransom which the airline is only too willing to pay.

Meanwhile, Capt Anderson (Van Johnson), who had appeared the insouciant handsome epitome of the airline pilot of the kind you saw in advertisements, is sweating profusely under the pressure as the cabin crew begin to search for the bomb. The passengers are not quite as terrified as you’d expect, most sitting in their seats, and i’ts left to celebrity George Ducette (John Saxon) to kick up a ruckus until put in his place by an anonymous army corporal (Michael Sarrazin) who has a distinct aversion to bombs and so far has sat rigid in his seat.

The hijacker keeps everyone on their toes by constantly moving from phone to phone. There’s a hiccup when the delivery van carrying the ransom has an accident and the cash is obliterated. By this point the hijacker, in a bar, is getting drunk and his iron control is tested by the news. The plane, meanwhile, is running out of fuel and Capt Anderson has long run out of patience.

Turns out the bomber isn’t the evil genius you expect. He’s been cast aside by the American dream, his considerable talents overlooked, and he wants everyone to know that he’s worth more. Unfortunately, he doesn’t get his moment in the sun, either literally having made off with the money, or by having his face splashed over the front pages of newspapers.

When he dies of a heart attack, the plane still circling and fuel levels dangerously low and now unable to locate the bomb, that’s a heck of a fabulous twist. But what Rod Serling takes away with one hand, he gives with the other, and the pilot soon works out that if he lands at a high altitude airfield he’ll prevent the bomb exploding.

Safely on the ground, we come to the third twist. The hijacker had deposited the bomb in Capt Anderson’s flight bag, carelessly left lying around at the airport. The final twist is the revelation that Thompson’s wife was on board.

What had every opportunity of becoming a run-of-the-mill thriller, especially since we are light on passenger drama (no pregnant women about to give birth, no kids or nuns to claw at our sentiments), segues into something more interesting as it delves into the cracking up of the hijacker and intimation that soldiers returning from Vietnam do not feel like heroes.

Edmond O’Brien is the pick, but Van Johnson possibly the most courageous in filleting his screen persona. You wouldn’t have predicted Michael Sarrazin’s later success from this performance, nor that Jack Lord would hit a home run in television’s Hawaii Five-O (1968-1980).

Ably directed by William Graham (Waterhole #3, 1967) and although, technically, all he has to do is point the picture in the direction of the twists, he brings more by allowing Edmond O’Brien to humanize his character.

I saw this as the supporting feature to Carry On Doctor and as a youngster never came out of a cinema more scared. Originally it was a made-for-television number though yanked after only one screening after airlines, not surprisingly, objected, so, as with many hard-to-find pictures it entered the cult zone in the USA.

As YouTube is often the curator of cult you can find it there.