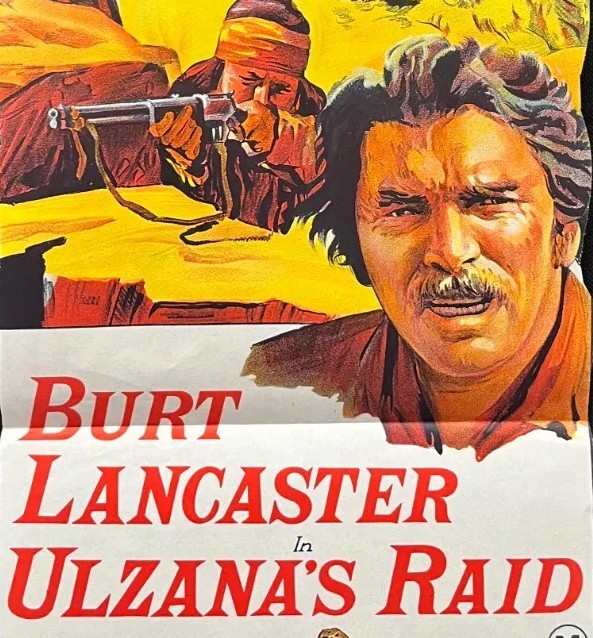

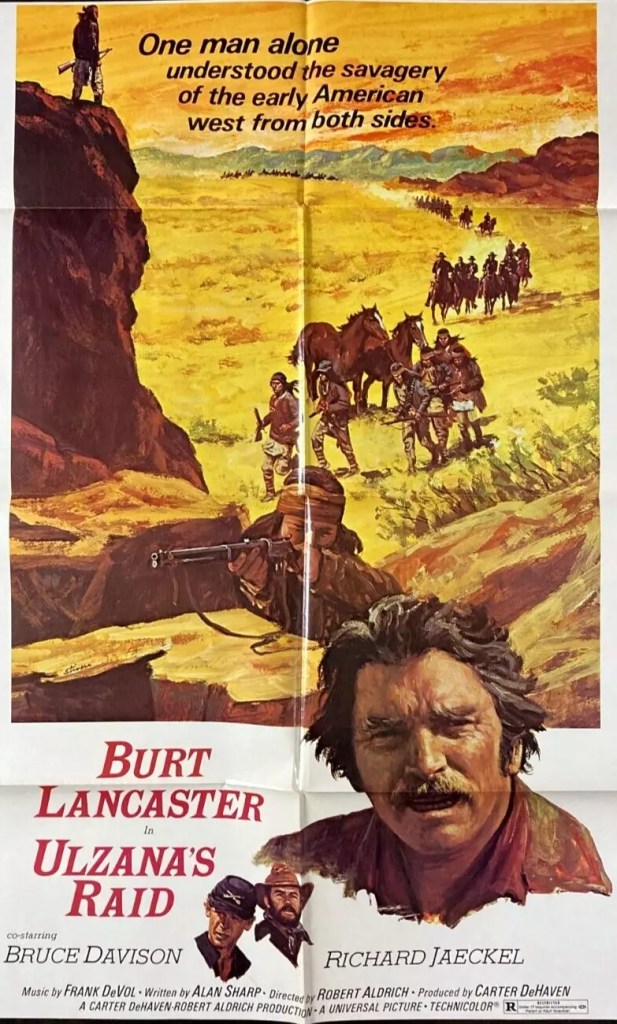

Still stands up as an allegory for the Vietnam War, superior American forces almost decimated by a small band of Apaches engaging in guerilla warfare. After the consecutive flops of Castle Keep (1969) and The Swimmer (1969), Burt Lancaster had unexpectedly shot to the top of Hollywood tree on the back of disaster movie Airport (1970) and consolidated his position with a string of westerns, which had global appeal, of which this was the third. After the commercial high of The Dirty Dozen (1967), director Robert Aldrich had lost his way, in part through an ambitious attempt to set up a mini-studio, his last four pictures including The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968) and The Killing of Sister George (1969) all registering in the red.

Riding a wave of critical acclaim was Scottish screenwriter Alan Sharp whose debut The Last Run (1971) turned on its head the gangster’s last job trope, and its lyrical successor The Hired Hand (1971) had stars and directors queuing up. Here he delivers the intelligent work for which he would become famous, melding Native American lore with a much tougher take on the Indian Wars and the cruelty from both sides.

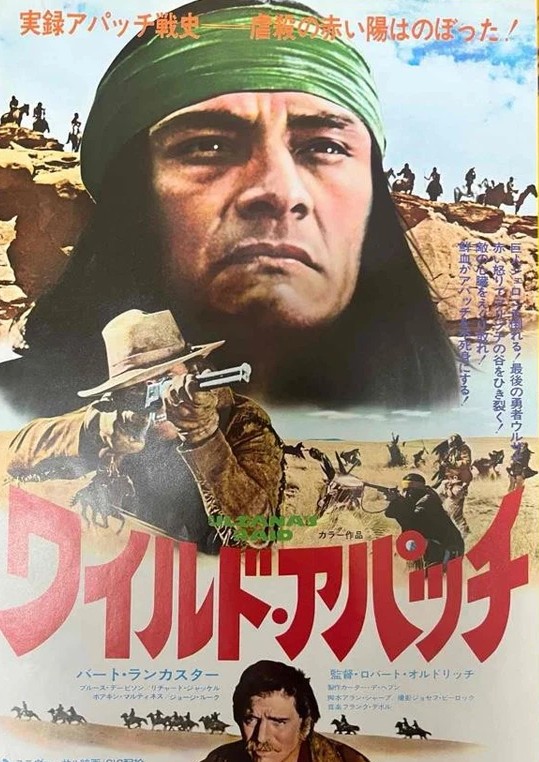

The narrative follows two threads, the duel between Ulzana (Joaquin Martinez), who has escaped from the reservation, and Army scout MacIntosh (Burt Lancaster); and the novice commander Lt DeBuin (Bruce Davison) earning his stripes. In between ruminations on Apache culture, their apparent cruelty given greater understanding, and some conflict within the troops, bristling at having to obey an inexperienced officer, most of the film is devoted to the battle of minds, as soldiers and Native Americans try to out-think each other.

Shock is a main weapon of Aldrich’s armory. There’s none of the camaraderie or “twilight of the west” stylistic flourishes that distinguished Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) or The Wild Bunch (1969). This is a savage land where a trooper will shoot dead the female homesteader he is escorting back to the fort rather than see her fall into the hands of the Apaches, following this up by blowing his own brains out so that he doesn’t suffer the same fate.

What such fate entails is soon outlined when another homesteader is tortured to death and another woman raped within an inch of her life, the fact that she survives such an ordeal merely a ploy to encourage the Christian commander to detach some of his troops to escort her safely home and so diminish his strength. Instead, in both pragmatic and ruthless fashion, she is used as bait, to tempt the Apaches out of hiding.

The Apaches have other clever tools, using a bugle to persuade a homesteader to venture out of his retreat, and are apt to slaughter a horse so that its blood can contaminate the only drinking water within several miles.

Key to the whole story is transport. The Apaches need horses. These they can acquire from homesteaders. Once acquired, they are used to fox the enemy, the animals led across terrain minus their riders, to mislead the pursuing cavalry and set up a trap. MacIntosh and his Native American guide, Ke-Ni-Tay (Jorge Luke), uncover the trickery and set up a trap of their own. However, the plan backfires. Having scattered the Apache horses, the Apaches redouble their determination to wipe out the soldiers in order to have transport.

There’s a remarkable moment in the final shootout where the soldiers hide behind their horses on the assumption that the Apaches will not shoot the horses they so desperately need. But that notion backfires, too, when they are ambushed from both sides of a canyon.

The twists along the way are not the usual narrative sleight-of-hand but matter-of-fact reversals. The soldiers do not race on to try and overtake their quarry. To do so would over-tire the horses, and contrary to the usual sequences of horsemen dashing through inhospitable terrain, we are more likely to see the soldiers sitting around taking a break. Ulzana is not captured in traditional Hollywood fashion either, no gunfight or fistfight involving either MacIntosh or the lieutenant. Instead, it’s the cunning of Ke-Ni-Tay that does the trick.

There are fine performances all round. Burt Lancaster is in low-key mode, Bruce Davison (Last Summer, 1969) holds onto his Christian principles so far as to bury the Apache dead rather than mutilate them, as was deemed suitable revenge by his corps, but his ideas of extending a hand of friendship to the enemy are killed off. Richard Jaeckel (The Dirty Dozen) communicates more with looks exchanged with MacIntosh than any dialog. Robert Aldrich is back on song, but owes a great deal to the literate screenplay.

Quentin Tarantino acclaimed this and I can’t disagree.