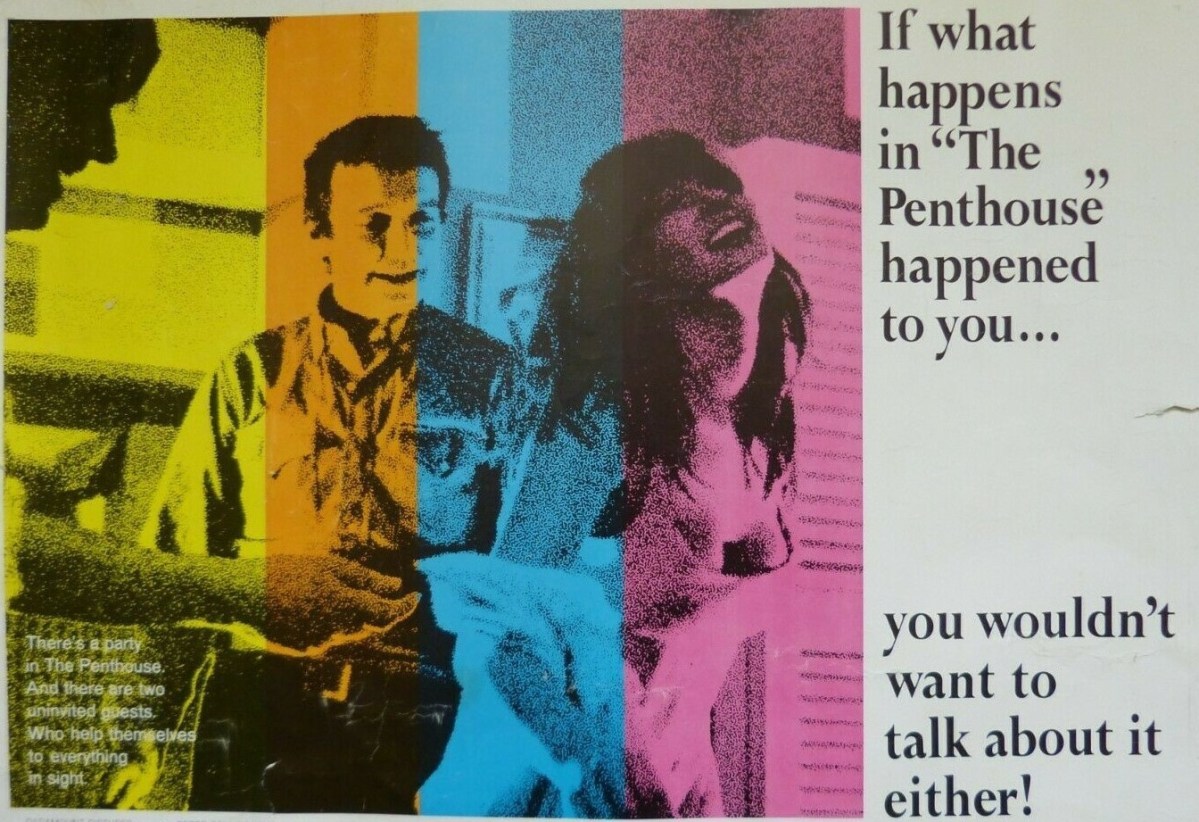

Visceral home invasion thriller that ignited the genre and triggered later more controversial offerings like The Straw Dogs (1971) and A Clockwork Orange (1971). Made virtually on one set for the indescribably minute sum of £100,000, it is charged with Pinteresque dialog and aberrant philosophy. The genre splits into those pictures where the occupants have more than a good chance of avoiding their fate, the focus on the invaded pitting their wits against the invaders – classic examples being The Straw Dogs or more recently Panic Room (2002) – and those where the victims are mercilessly tormented, such as, in grueling detail, here.

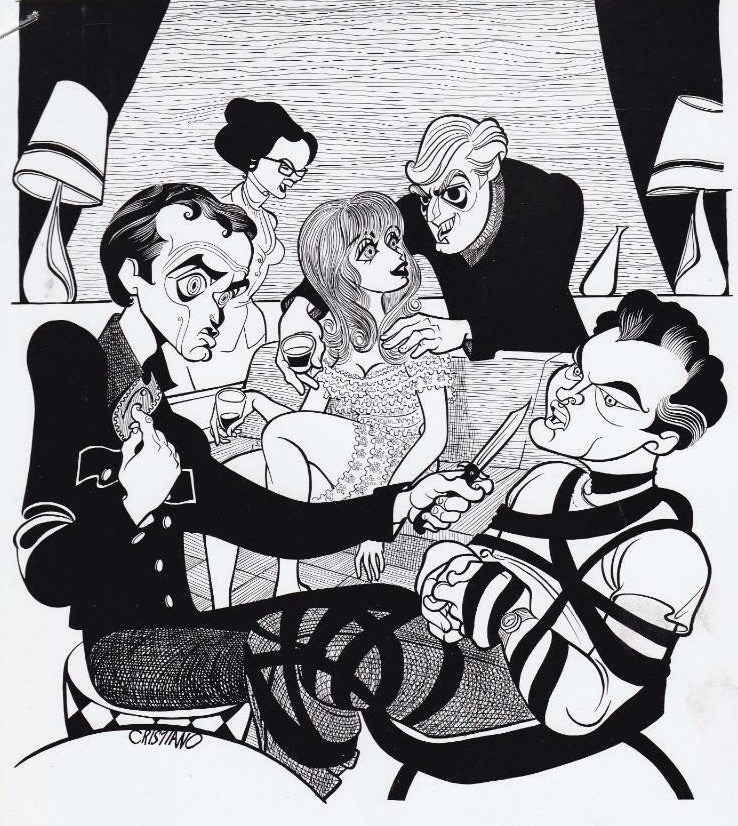

As one of the perks of his job cocky married real estate agent Bruce (Terence Morgan) takes advantage of an expensive unoccupied apartment on his company’s books – “in the happy position to take advantage of my clients’ generosity in their absence” as he puts it – to enjoy an illicit tryst with mistress Barbara (Suzy Kendall). But when she answers to the door to two men coming to read the gas meter, their lives are turned upside down.

Tom (Tony Beckley) and Dick (Norman Rodway) are, of course, bogus and armed with a knife quickly take control, trying up Bruce and pouring alcohol down Barbara’s throat. As part of the overall creepiness, there is a sense that this is no casual visit, but that it has been planned, as if someone somewhere is familiar with the set-up, and there a debt, if only a moralistic one, to pay as a deterrent to the era’s permissiveness. Minus the knife, they would have passed as harmless. But never was their such difference between word and action, except for what they are capable of you could easily be persuaded that are in fact camp and bitchy.

The bound Bruce’s is spun round in a chair and can only watch as the men begin to strip Barbara. His only defence is verbal, trying to set the two men against each other, suggesting that Tom treats Dick as his assistant. But the relationship between the two criminals constantly shifts as if they were in passive-aggressive relationship. You don’t learn much about them until the end, so basically you have to rely on what they say about themselves, which is very little. They are prone to philosophic observation or interrogate Bruce about his possessions or extract from Barbara an unexpected ambition to be a painter.

The men take it in turns to torment Bruce while the other is in the bedroom with Barbara. Where Bruce resists verbally, Barbara gives in almost right away, but there is never the sense that this is in any way consensual, just that she is too drunk to defend herself – the first drink is a full glass of whisky forced down her throat – and the men have a knife. The invaders make constant reference to a character called Harry. That person’s eventual appearance provides a whole new range of twists.

It’s a film full of menace. Sexual tension, mind games, claustrophobia and the threat of physical violence never dissipate. Because it is rationed out, the brutality is all the more shocking. But it is brilliantly directed. In his debut British director Peter Collinson (The Italian Job, 1969) uses the camera to suggest we are in anything but an enclosed space. In one long sequence the camera does not move, in another scene it turns 360 degrees – Antonioni’s use of this device in The Passenger (1975) was credited as innovative – and at other times it twists and turns as if turning the characters inside out, suggesting some of the dizziness, the dramatic speed of change of feelings, that the stunned victims are enduring. At times it feels like an arthouse movie. At other times like a deranged B-picture.

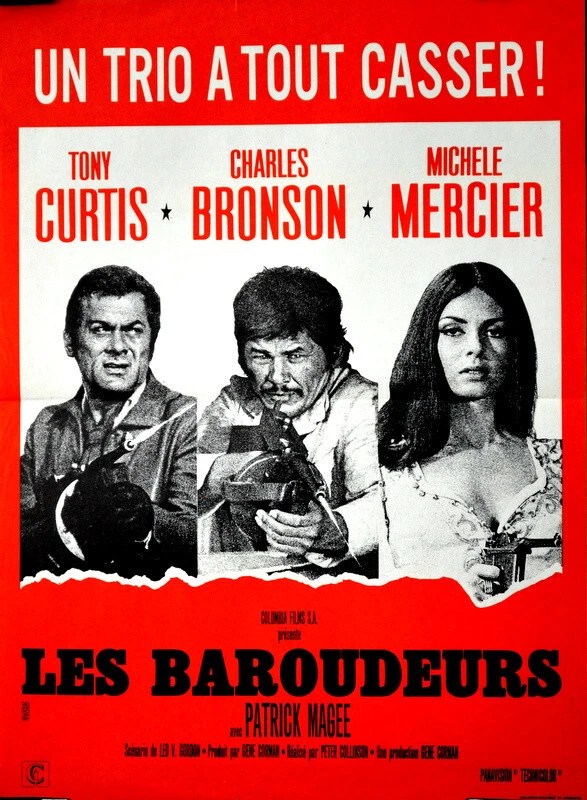

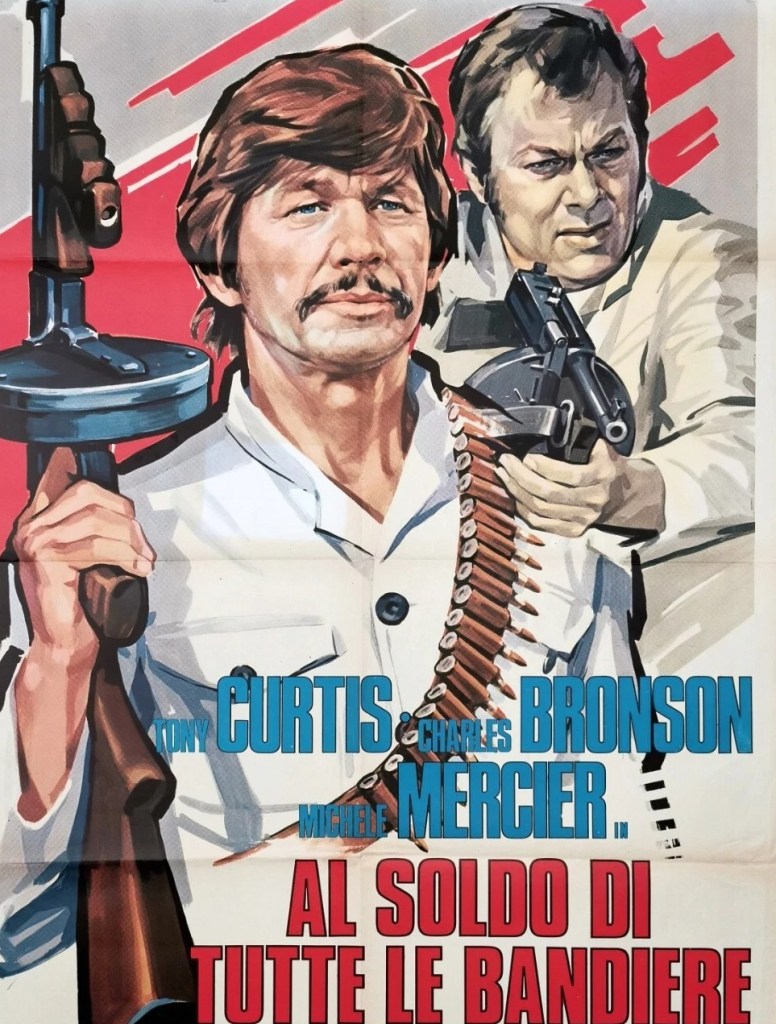

The cast are all excellent. Tony Beckley (The Lost Continent, 1968) makes the best of a role of a lifetime, Norman Rodway (Four in the Morning, 1965) the more quietly psychotic sidekick. Terence Morgan (The Sea Pirate, 1966) has less to do but Suzy Kendall (Fraulein Doktor, 1969) is superb as the enigmatic girlfriend. Look out for Martine Beswick (Prehistoric Women, 1967) in a small part. Collinson wrote the screenplay based on a play The Meter Men by Scott Forbes.

Cultural note: “Tom, Dick and Harry” are considered such quintessentially British names that anyone familiar with this would understand immediately that they were a) pseudonyms and b) intended as a twisted kind of joke.

No sign of this being available on Amazon. Ebay is probably your best bet. There’s a copy on YouTube but it ain’t a good print.