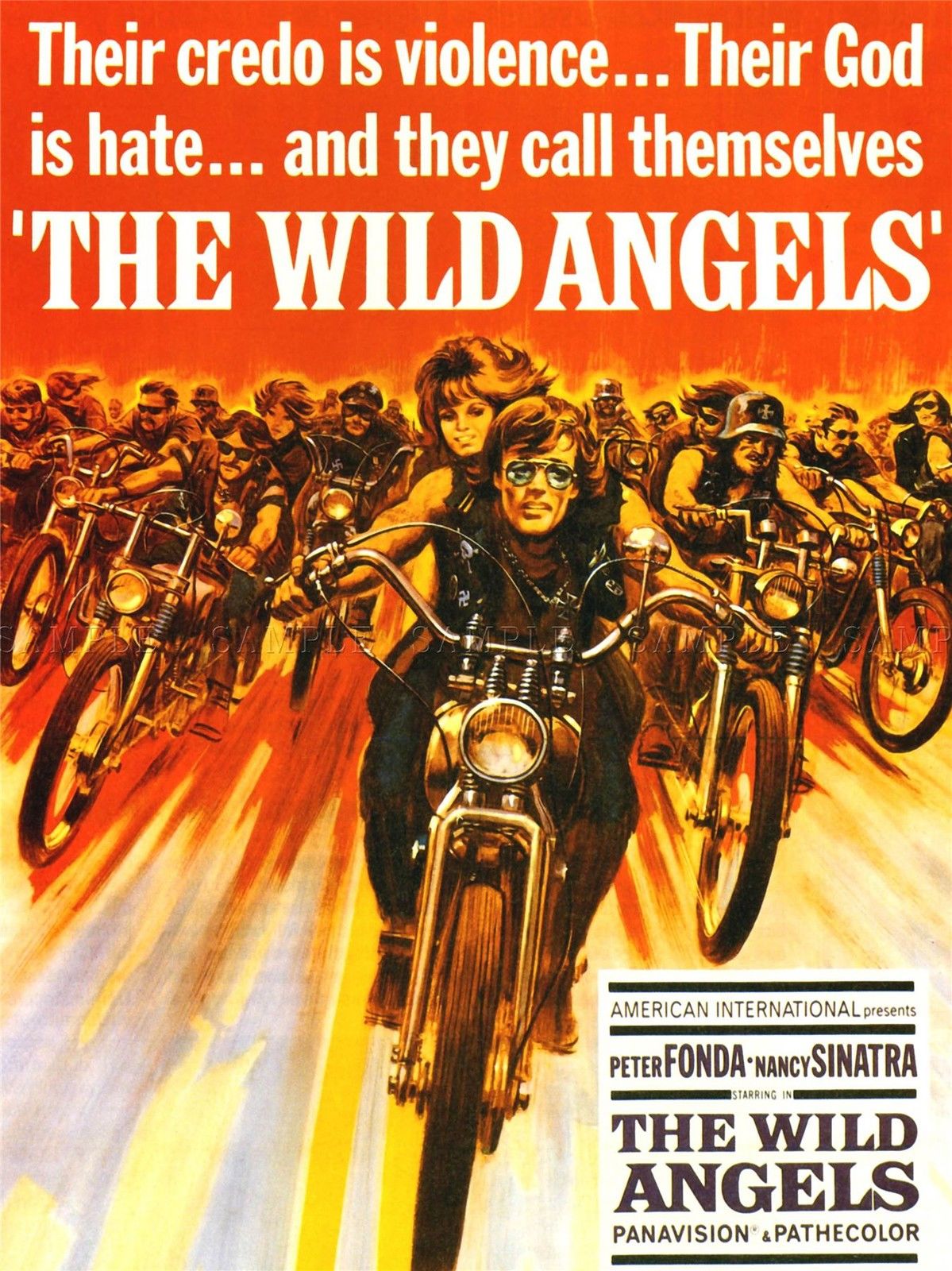

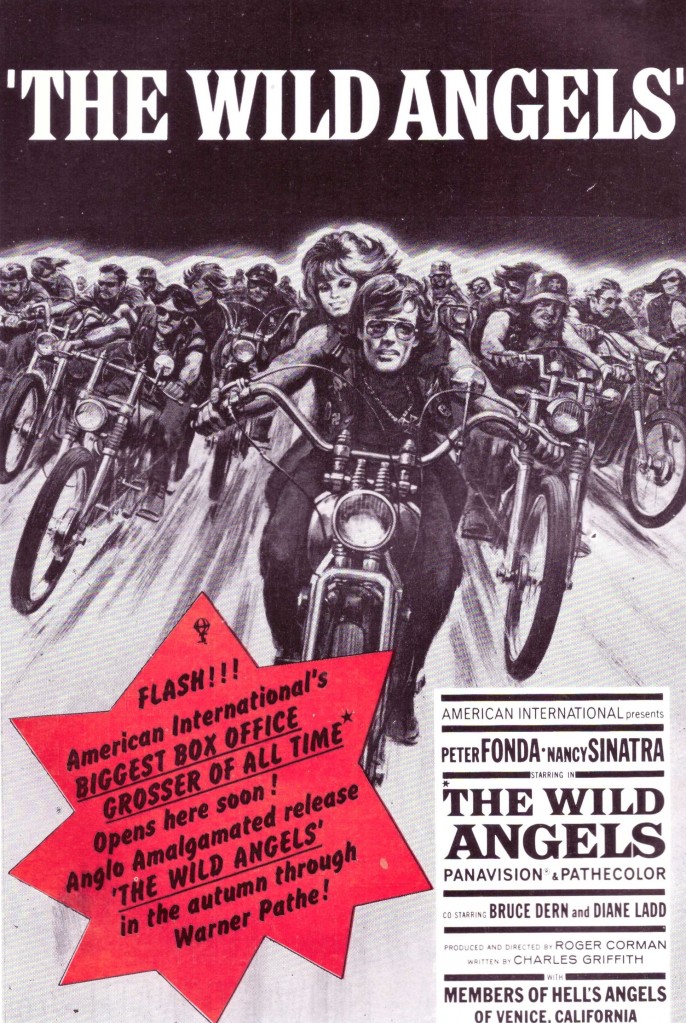

Riders stretched out across a sun-baked valley – you could be harking back to the heyday of the John Ford cavalry western instead of the biker picture, the first in the American International series, that sent shockwaves through society and laid the groundwork for the more philosophical Easy Rider (1969) a few years later. Long tracking shots are in abundance. You might wonder had director Roger Corman spent a bit more on the soundtrack, the bikers just worn beads instead of swastikas, and been the victims rather than the perpetrators of violence how this picture would have played out critics- and box office-wise.

The Wild Angels set up a template for biker pictures, one almost slavishly followed by Easy Rider, a good 15 per cent of the screen time allocated to shots of the Harley-Davidson riders and scenery, and a slim plot. Here Heavenly Blues (Peter Fonda), trying to recover a stolen bike, leads his gang into a small town where they beat up a bunch of Mexican mechanics, are pursued by the cops, hang out and indulge in booze, drugs and sex, and then decide to rescue the badly-injured Joe (Bruce Dern) from a police station. This insane act doesn’t go well and after Joe dies they hijack a preacher for a funeral service that ends in a running battle with outraged locals and the police.

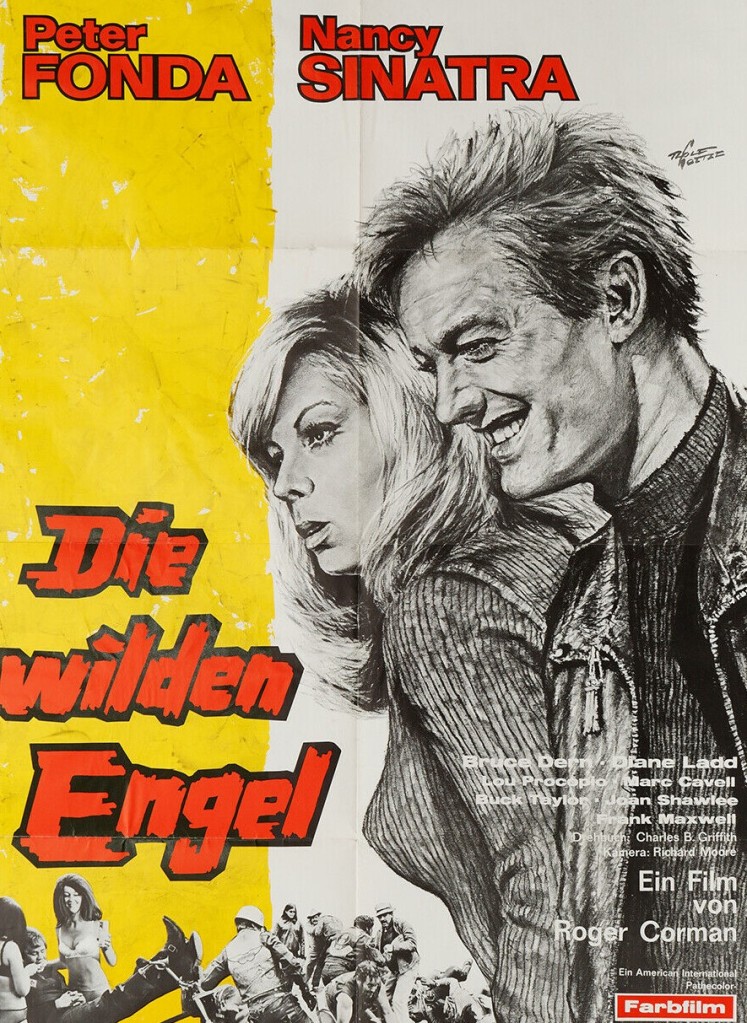

There’s an odd subplot, given the lifestyle of freedom and independence, of Monkey (Nancy Sinatra) trying to get a romantic commitment out of Heavenly. Conversely, Heavenly, rejecting the traditional shackles of love, finds himself trapped by grief, eventually and quite rightly blaming himself for Joe’s death, and apparently turning his back on the Angels to mourn his buddy. The decline – or growing-up – of Heavenly provides a humane core to a movie that otherwise takes great pride in parading (and never questioning) excess, not just the alcohol and drugs, but rape of a nurse, gang-bang of Joe’s widow (Diane Ladd), violence, corpse abuse, and wanton destruction.

A ground-breaking film of the wrong, dangerous, kind according to censors worldwide and anyone representing traditional decency, but which appealed to a young audience desperate to find new heroes who stood against anything their parents stood for. In a decade that celebrated freedom, the bikers strangely enough represented repression, a world where women were commodities, passed from man to man, often taken without consent, and racism was prevalent.

Roger Corman (The Secret Invasion, 1964) was already moving away from the horror of his early oeuvre and directs here with some style, the story, though slim, kept moving along thanks to the obvious and latent tensions within the group. If he had set out to assault society’s sacred cows – the police, the church, funeral rites – as well as a loathing of everything Nazi, he certainly achieved those aims but still within the context of a group that epitomized some elements of the burgeoning counterculture.

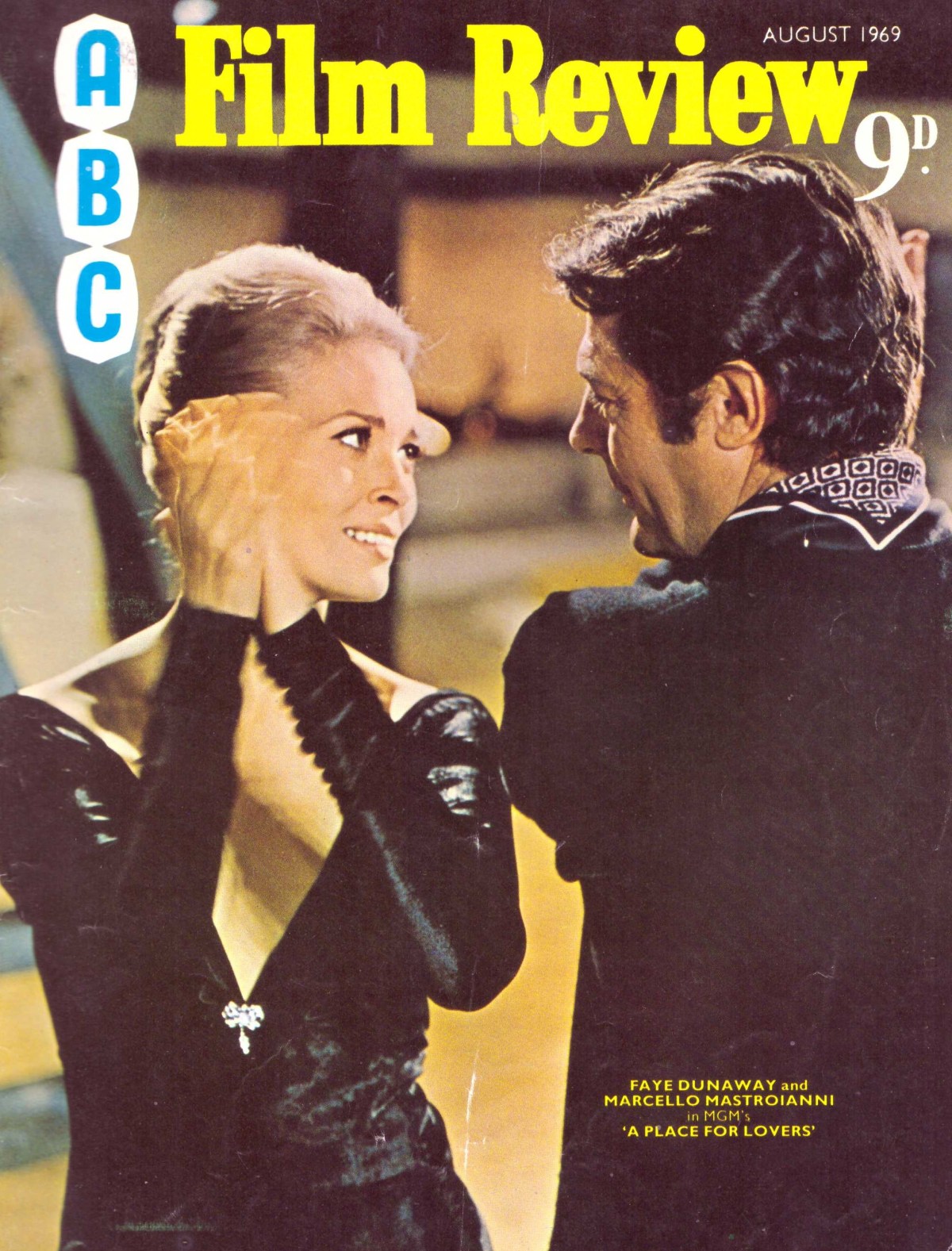

In retrospect this appears an ideal fit for Peter Fonda, but that’s only if viewed through the prism of Easy Rider for, prior to this (see the “Hot Prospects” Blog) he was being groomed as a romantic leading man along the lines of The Young Lovers (1964). Bruce Dern (They Shoot Horses, Don’t They, 1969) was better suited, his screen persona possessing more of the essential edginess while Michael J. Pollard (Bonnie and Clyde, 1967) was the eternal outsider.

Rather surprising additions to the cast, either in full-out rebel mode as with Nancy Sinatra (The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini, 1966) or hoping appearance here would provide career stimulus as with movie virgins Diane Ladd (Chinatown, 1974) and Gayle Hunnicutt (P.J. / A New Face in Hell, 1968). Sinatra certainly received the bulk of the media attention, if only for the perceived outrage of papa Frank, but Hunnicutt easily stole the picture. Minus an attention-grabbing role, Hunnicutt, long hair in constant swirl, her vivid presence and especially her red top ensured she caught the camera’s attention.

Charles B. Griffiths (Creature from the Haunted Sea, 1961) is credited with a screenplay that was largely rewritten by an uncredited Peter Bogdanovich (The Last Picture Show, 1971).