The spate of slapstick-led comedies like It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) and The Great Race (1965) and British featurettes such as The Plank (1967) did not suddenly appear out of nowhere as was often the case with a moribund genre. The slapstick revival came by way of television. In the 1950s U.S. networks were screening silent shorts featuring Laurel and Hardy, Charlie Chaplin, and some of the Hal Roach and Mack Sennett output.

The driving force behind the big screen resurgence of interest in silent comedy was Robert Youngson who spent $100,000 in 1957 on what purported to be a new documentary The Golden Age of Comedy. In fact it was a good excuse for a compilation of old movie clips featuring Laurel and Hardy, Harry Langdon and actresses known for their comic ability such as Jean Harlow and Carole Lombard. But while the television audience was weighted towards the young, Youngson’s picture reached a more appreciative adult audience in the arthouses, which would prove to be the bedrock for the ambitious revitalizing of the careers of other greats from the Hollywood peak years.

The Golden Age of Comedy was hugely successful, taking $500,000 in rentals. Since arthouses notoriously shared of lot less of their box office with studios there was a fair chance that the gross was in the region of $1.5 million, a tremendous return on investment, and opening the door for further sequels.

Silent comedy also crossed national boundaries. Modern dialogue-driven Hollywood comedies often found it hard to gain a foothold overseas. But The Golden Age of Comedy film was Twentieth Century Fox’s top grosser in India and huge in Italy.

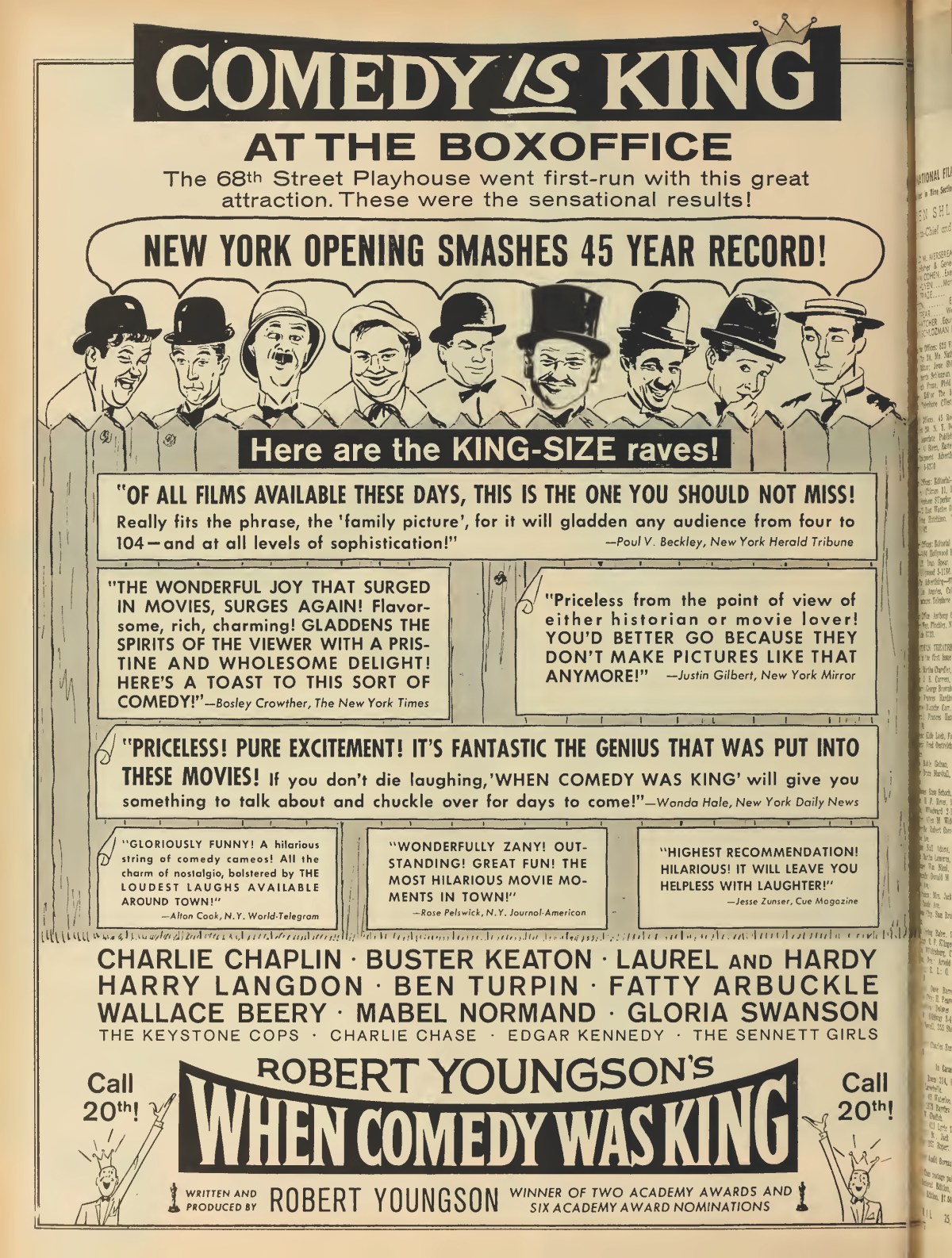

Follow-up When Comedy Was King (1960) smashed box office records in New York at the 370-seat arthouse the 68th St Playhouse and at prices ranging from 90c to $1.65 playing to an estimated 10,000 moviegoers and running for another eight weeks. That gave Fox the greenlight to stick it out on the more commercial circuits as a supporting feature. But that was just the tip of the compilation iceberg, especially when other studios got into the act.

Hardly a year went by without another compilation – from the Youngson camp emerged Days of Thrills and Laughter (1961) and 30 Years of Fun (1963). MGM put marketing muscle behind the producer’s The Big Parade of Comedy (1964) to the extent that it collected rave reviews from Newsweek and the New York Times and the studio held seminars for exhibitors on “sight comedy.” The inevitable double bill When Comedy Was King/Days of Thrills and Laughter appeared in 1965.

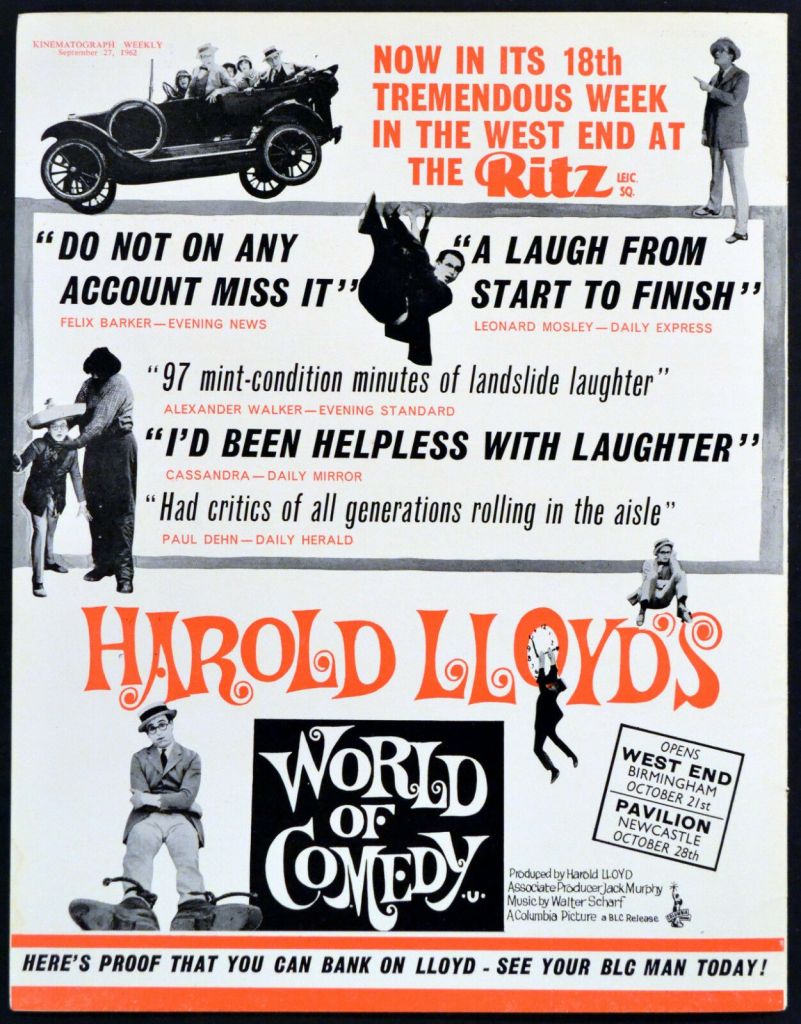

Harold Lloyd owned the copyright to all his films so his work was not chopped up piecemeal to satisfy the demands of a compilation. Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy (1962) showed the comedian at the peak of his game. It combined eight scenes from silent and sound films Safety Last (1923), Why Worry (1923), Girl Shy (1924), Hot Water (1924), The Freshman (1925), Feet First (1930), Movie Crazy (1932) and Professor Beware (1938). His trademark spectacles were incorporated into the advertising. Follow-up Funny Side of Life (1963) included a complete version of The Freshman.

Mining a different silent tradition and with less emphasis on comedy was The Great Chase (1962) – including a shortened version of The General (1926) – which featured stunts by Douglas Fairbanks, Buster Keaton, William S. Hart and Pearl White.

The Buster Keaton revival had been initiated in less commercial fashion by Raymond Rohauer who had begun staging festival sof his films in arthouses. He tracked down prints of long-lost films in France, Denmark and Czechoslovakia but his compilations Buster Keaton Rides Again (1965) and The Great Stone Face (1966) were more successful abroad than at home.

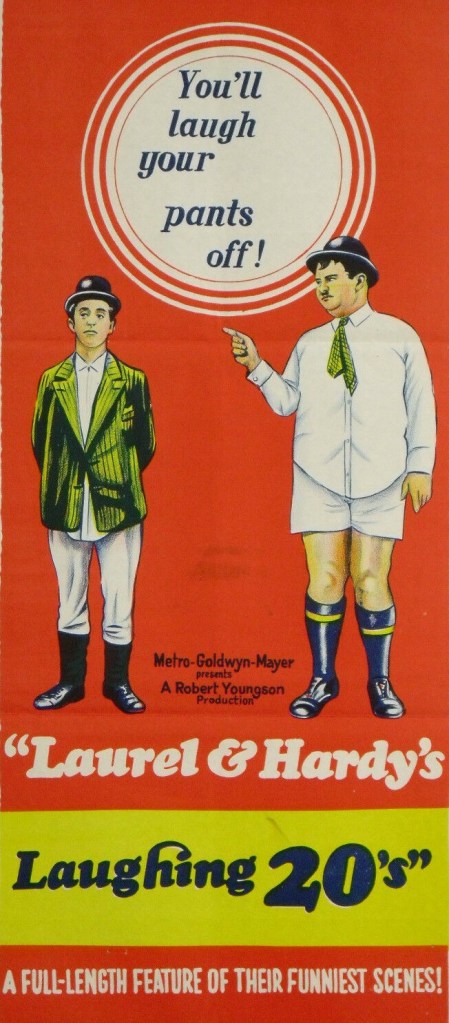

Blake Edwards’ The Great Race was dedicated to Laurel and Hardy who had become more prominent on both small-screen and big-screen thanks in part to the initial Youngson compilations. MGM were first out the traps with Laurel and Hardy’s Laughing 20s (1965). Then came producer Jay Ward’s The Crazy World of Laurel and Hardy (1966) and The Further Perils of Laurel and Hardy (1967) followed by a collection of colorized shorts The Best of Laurel and Hardy while Hanna-Barbera launched a cartoon series on television in 1966 and Pillsbury sold Laurel and Hardy donuts.

SOURCES: Brian Hannan, Coming Back to a Theater Near You: A History of the Hollywood Reissue 1914-2014 (McFarland, 2016), pages 200-205; “Youngson Anthologies of Silents Continue Showing Coin Potential,” Variety, October 19, 1960, p13; “Picture Grosses,” Variety, March 9, 1960, p8; Advertisement, “Sleeper of the Year,” Box Office, October 5, 1964, p7; “MGM Sets Fun Campaign for Laurel and Hardy,” Box Office, September 20, 1965, p112; “Comedy Seminar Helps MGM Film Promotion,” Box Office, December 13, 1965, p94; “Pillsbury Acquires Rights for Laurel and Hardy Donuts,” Box Office, October 23, 1966, p27; “Archivist Raymond Rohauer,” Los Angeles Times, November 20, 1987.