Over-long, over-hyped and over-cast. Pretty much an early example of virtue-signalling, exposing corruption in a dictatorship (Haiti), but offering more through the singular self-deception of the main characters. An element of sleight-of-hand is also practiced on an audience enticed by four big stars “above the title” comprising three Oscar winners and one multiple nominee. Luckily, the ironic in-joke of naming characters with traditional English names – Smith, Jones and Brown – would probably pass most people by.

Brown (Richard Burton), a hotelier, is present throughout but Major Jones (Alec Guinness) appears only briefly at the beginning then disappears until late on to spike the plot. Martha (Elizabeth Taylor), the adulterous love interest, pops up sporadically as does her husband Ambassador Pineda (Peter Ustinov). There’s not much of a story, Brown, cynical about the dictatorship, is friendly with a rebel leader, Jones is an ineffectual arms dealer, and missionary couple the Smiths (Paul Ford and Lillian Gish) offer comic relief until barbarity rears its head.

Great play is made of naivete but the film suffers from the Hollywood curse of only being able to examine foreign politics through the prism of a (white) American or Englishman. At the time it might have been shocking to see brutality so convincingly dispensed, and there is, also, in Mondo Cane fashion, too much time spent on strange ritual, but at the same time, of course, the U.S. was inflicting its own barbarities on the Vietnamese.

On the other hand, Brown is exactly the kind of foreigner who believes things must improve because, damn it all, he’s British and bad things can’t happen to a Brit in a strange land. He is convinced he will be able to sell a hotel located in a war-torn country, persists in believing Martha will abandon husband and son, and convinces himself he is the very man the rebels have been looking for.

Jones mistakenly believes everyone is taken in by his hail-fellow-well-met routine and his tales of heroism in World War Two jungles, thinks he is in with a chance with Martha and that his gun-running activities will avoid detection. The ambassador thinks his wife will not leave him as long as he turns a blind eye to her affairs. And Martha, probably wondering why she married such a buffoon, can’t work out to dump him. Everyone who has much to lose appears to be continually on a precipice and it’s hard to see what they could gain from their actions.

They are all misfits, “comedians,” stuck in the rut of their own destiny, unable to change.

Nobody is more gullible than those who dupe themselves and the film comes into its own when it sets personal delusion against political naivete. In narrative terms Jones is the most obviously unmasked but the others are no less shown to be foolhardy in their expectations.

This had all the hallmarks of a prestige picture, initially planned as a roadshow, around $2 million spent on the above-the-line cast, another chunk on buying the rights to the Graham Greene bestseller and assigning the author the screenplay, location shooting in Dahomey.

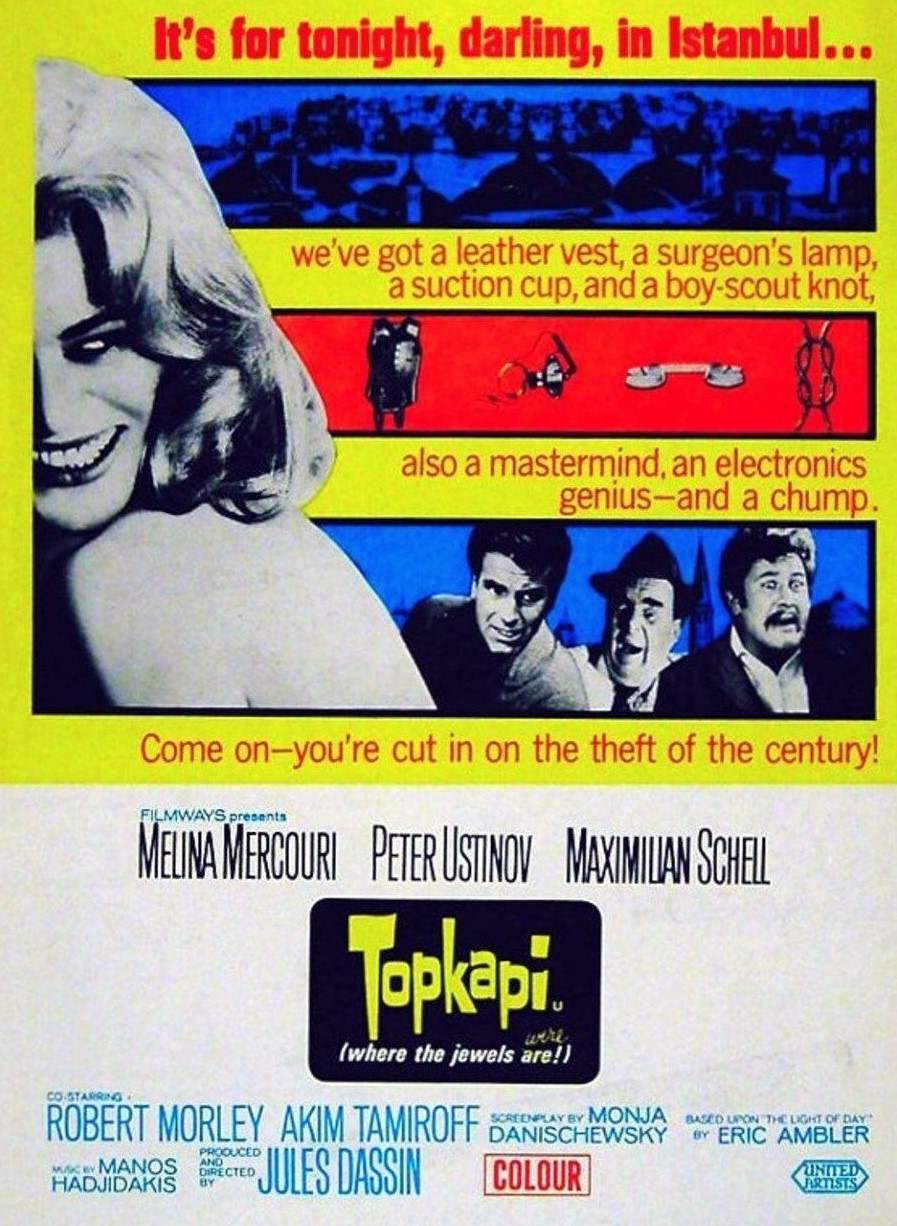

Don’t expect oratorical fury from Richard Burton (The Bramble Bush, 1960) nor outbursts of angst from Elizabeth Taylor (Secret Ceremony, 1969). There’s something almost comically homely in their deception and in the outwardly confident Brown perceiving Jones as a love rival. Alec Guinness (The Quiller Memorandum, 1966) is the big treat, an upmarket con man, his boisterous voice and mannerisms far removed from his more usual introspective performances. Peter Ustinov (Topkapi, 1964), a bit too fidgety for my liking, nonetheless attracts sympathy as the man who is batting above his weight in snaring a trophy wife he knows he cannot hold onto.

Burton was the odd one out in the Oscar rankings. Despite five nominations by this stage, he had never taken home the statuette. Elizabeth Taylor, by contrast, had won twice, for Butterfield 8 (1960) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966), Guinness once for Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Ustinov also twice Spartacus (1961) and Topkapi.

However, in some senses if you remove the star turns, you are left with a rawer picture, and director Peter Glenville (Becket, 1964) captures much of the personal intensity of the novel. Taylor, in particular, misses the mark. Although playing a German, she never once bothers attempting an accent. Had Burton been the sole star, the movie would have worked much better since his low-key playing would not have been so much at odds with other actors.

There’s a host of striking turns from supporting stars, ranging from silent film star Lillian Gish (The Unforgiven, 1960) to Roscoe Lee Brown (Topaz, 1969), James Earl Jones (The Great White Hope, 1970), Raymond St Jacques (Uptight, 1968) and Cicely Tyson (Sounder, 1972).