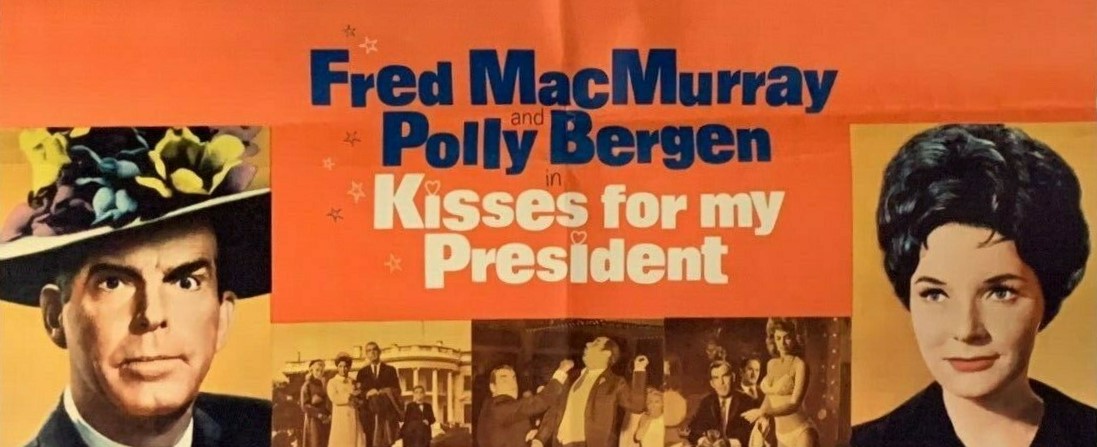

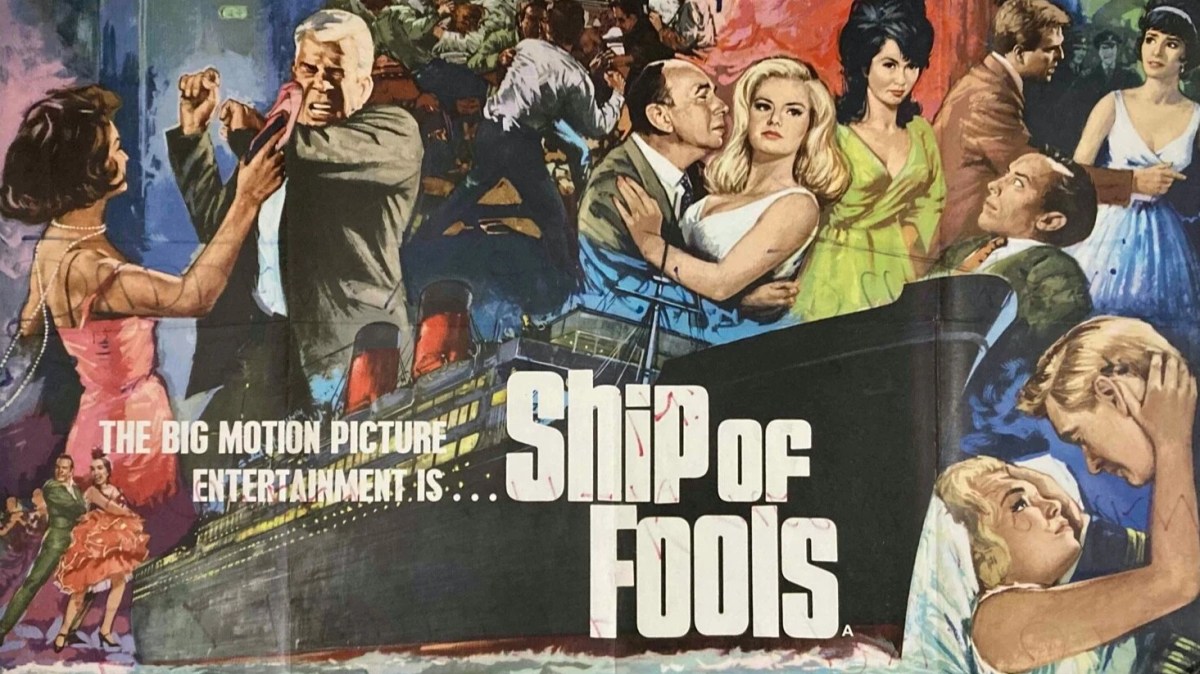

The concept of a female President was so alien to Hollywood that the only conceivable approach was to make it the story of the husband taking up the chores of the First Lady.

Having perfected his double takes and pratfalls on a string of Disney comedies Fred MacMurray plays Thad McCloud, straight man to incoming President Leslie McCloud (Polly Bergen) and after the screenwriters have exploited virtually every joke in the gender switch catalog it settles down to a more serious exploration of power.

Thad nurses a wounded ego after playing second fiddle to his more powerful wife, joining the anteroom queue to see her, any romantic notions interrupted by the telephone, and not enjoying his new role as chief menu selector and supporter of charities. So he’s a prime target for another powerful woman, Doris (Arlene Dahl), the head of a perfume company, an old flame who seduces him into taking charge of their male toiletries division. Meanwhile, Leslie challenges the foreign aid expectations of South American dictator supreme Valdez (Eli Wallach) while Thad gets into trouble escorting him to a night club.

Power is exploited not just by Valdez for whom financial aid means corruption but by the President’s children, the teenage Gloria (Anna Capri) who races round Washington in fast cars driven by louche boyfriends in the knowledge that she can’t be arrested, and younger Peter (Ronnie Dapo) who attacks schoolmates knowing Secret Service agents will protect him from retaliation. The sexually frustrated Thad, excited at the prospect of developing a new masculine-oriented range of perfumes, does not realise that Doris, far from leading him into the sack, is merely leading him by the nose, having no intention of using his ideas, her sole interest being getting the presidential endorsement.

There are certainly some amusing sequences – Thad getting lost in the White House, discovering his bedroom is more luxuriously appointed, getting stoned on pills to make him relax for a television show, and his reactions to watching the dictator spend his country’s foreign aid on fast cars, speedboats and loose women (a stripper named Nana Peel). The children are not just entitled but vicious with it. And Leslie, the most powerful person in the country nonetheless impotent in the face of a rebellious brood.

There’s a welcome element of Yes, Minister (the British television comedy ridiculing political bureaucracy) as both wife and husband face up to the over-complications of White House life. And there are some good lines. Spouts Thad: “A man needs an office especially when he has nothing to do.” Without a hint of irony, Leslie tells him, “Nobody expects you to vegetate just because you’re married to the President.”

And at least the character of Leslie is treated with respect. There’s no falling back on stereotypes. She’s not out of her depth, or given to tantrums or bouts of tears, she’s not outmanoeuvred by more clever men and she doesn’t come running to Thad for help.

That said, you can’t help thinking of the picture they could have made if Leslie had been the complete focus, her battles with the political male hierarchy, the laws she would have attempted to enact, introducing a feminine perspective to the corridors of power. Even so, as written, she is strong-willed enough to strip the self-indulgent Vasquez of foreign aid and deal with the consequent political fall-out.

Generally under-estimated as an actor, and now in his third decade as a star, the high points being Double Indemnity (1945) and The Apartment (1960), he had reinvented himself as a slapstick comedian with The Shaggy Dog (1959). His work had largely remained in that vein ever since so he was adept at underplaying this kind of character. Polly Bergen (Move Over, Darling, 1963) is spared the comedy and could have been in a different movie entirely, her scenes primarily taken seriously. Eli Wallach (The Moon-Spinners, 1964) gives the game away, over-acting to his heart’s content. Arlene Dahl (Sangaree, 1953) conjures up her Hollywood glamor heyday.

Hungarian blonde bombshell Anna Capri (Target: Harry, 1969) makes her movie debut. Variety’s Army Archerd had a cameo as did columnist Erskine Johnson. Beverly Powers (Jaws, 1975) plays the stripper.

This was the final picture in a 40-year career for German director Curtis Bernhardt (Possessed, 1947). Claude Binyon (North to Alaska, 1960) and Robert G. Kane (The Villain, 1979), in his movie debut, shared the screenplay credit.

Check out a Behind the Scenes for the Pressbook